Lupine Publishers | Open access Journal of Complimentary & Alternative Medicine

Keywords: Yoga; Therapy; Traumatic Brain Injury; Sleep; Mood; Depression; Anxiety; Adjustment

This project was funded by the Shepherd Center Research

Department located in Atlanta, GA.

To Know more Open Access Publishers Click on Lupine Publishers

Abstract

Sustaining a Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) has a significant effect

on an individual’s physical and mental abilities. Residual

effects of TBI include sleep and mood disorders. Sleep disorders include

any disturbance in an individual’s quality of sleep and

daytime functioning. Mood disorders include depression, anxiety, and

adjustment to injury. Rehabilitation after TBI involves a range

of therapeutic services in which a holistic approach to therapy

addresses both the mind and the body. Yoga may be used to improve

functioning for individuals with TBI. The purpose of this convergent

mixed methods study was to examine the influence of yoga on

the sleep and mood in individuals with TBI. This research study involved

an eight-week yoga intervention at a large rehabilitation

hospital in the southern United States. Seven individuals who sustained a

TBI were recruited for the intervention. Sleep and mood

were assessed pre-, mid-, and post-intervention. Upon completion of the

intervention, participants and their caregivers took part

in focus groups to share their perceptions of changes in sleep and mood.

Data were analyzed and describe the influence of yoga on

individuals with TBI. Quantitative data revealed no statistical

significance, though percent change calculations of pre- and post-data

showed a substantial decrease in anxiety and an improvement in

adjustment to injury. Qualitative data were consistent with the

calculated percent change in addition to an emerging theme of social

support amongst individuals with TBI.

Keywords: Yoga; Therapy; Traumatic Brain Injury; Sleep; Mood; Depression; Anxiety; Adjustment

Introduction

A Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is defined as an acquired

injury that is the result of direct damage to the brain [1]. A TBI

can occur quickly and unexpectedly, but often has a long-term

effect on an individual’s physiological and neurological abilities

[2,3]. In the United States, approximately 1.7 million people per

year are admitted to the emergency room due to sustaining a TBI

[4], many of whom continue to live with residual effects [5]. The

residual effects of a TBI include, but are not limited to, trouble

sleeping, changes in mood, and difficulty adjusting to life after

injury [6,7]. Sleep disorders are defined as any consistent internal

disturbance in sleep [8]. Regarding people with TBI, poor sleep

quality is common [7] and has the potential to decrease emotional

and physical abilities, as well as slow the recovery process [9]. In

addition to the negative impacts from sustaining a TBI, individuals

are also susceptible to mood disorders as a residual effect of TBI.

Common behavioral impairments for people with TBI include

mood disorders, which can manifest as depression, anxiety, and

adjustment to injury [3,6]. Depression is a common secondary

factor for clinical conditions related to TBI [10]. Depression

is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (DSM-5) [8] as depressed mood or loss of pleasure in

life activities for more than two weeks, change from an individual’s

baseline mood, and compromised functioning. Generalized anxiety

is defined in the DSM-5 as extreme or unrealistic worry for the

majority of the days within six months [8]. Anxiety after TBI may

first be seen as a normal reaction to trauma, but individuals with TBI

appear to have an increased risk of developing generalized

anxiety in comparison to the general population [11]. Individuals

with TBI also experience an adjustment to life after injury [12].

Level of adjustment after sustaining a TBI can be observed through

the presence of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and irritability [13].

Due to the physical, cognitive, and emotional impacts of

sustaining a TBI, treatment for TBI needs to be approached

from a multidisciplinary perspective. As an emerging element of

physical rehabilitation, complementary integrative health (CIH)

interventions are health practices used in combination with

traditional medicine [14]. CIH includes a wide variety of healing

interventions that counteract illness or assist in increasing health

and wellbeing [15]. CIH interventions, such as yoga, can be used

as a holistic and complementary treatment to address the physical

and mental needs of individuals with TBI [16-17].

In the West, yoga focuses on three main practices: breathing

(pranayama), meditation (dhyana), and physical poses (asanas)

[18]. Yoga interventions have been utilized in several rehabilitation

settings [19-22], for the purpose of providing a complementary form

of therapy. Research on the perceptions of yoga, when integrated into

inpatient rehabilitation hospitals, shows patients’ rehabilitation

was enhanced by the use of yoga due to the added benefit yoga

provided, including self-management skills and assisting longterm

recovery [21,23]. Yoga for individuals with TBI is likely a

useful intervention due to the adaptability of yoga sequences, the

potential physical and cognitive benefits, and the research pointing

to the potential sleep and mood benefits [19-24]. While there

is limited research on yoga for TBI, one small, exploratory study

found that when yoga was administered 16 times over the course

of eight weeks, individuals with TBI expressed improvement in

physical, emotional, and mental domains [25]. In an analysis of the

influence of yoga on sleep for people with TBI through sleep-wake

diaries, a substantial improvement in sleep quality was found after

eight weeks of yoga treatment [19]. Following an adapted yoga

group intervention for individuals with TBI, participants expressed

favorable improvements in comfort with approaching balance and

relaxation, as well as an increased self-awareness that helped with

sleep [26]. There is limited research on yoga for individuals with a

TBI and yoga, thus there is need for further studies related to the

influence of yoga on sleep and mood in this population. Therefore,

the purpose of this study was to observe, analyze, and discuss the

influence of yoga on TBI related to their sleep and mood.

Methods

Design

This convergent mixed methods pilot study examined the

influence of yoga participation on sleep and mood among individuals

with TBI. Quantitative data was collected using a repeated measures

design, with pre-, mid-, and post-intervention assessments given.

Qualitative data was collected through two post-intervention focus

groups, consisting of one focus group with participants and one

with the participants’ caregivers. Prior to the start of this study,

approval through the Rehabilitation Hospital’s Institutional Review

Board (IRB) and the Clemson IRB were obtained.

Recruitment and Participants

Purposeful, criterion-based sampling was employed in this

study to decrease the variation of diagnosis amongst subjects [27].

Fifteen individuals who sustained a TBI and were prior patients at

a large rehabilitation hospital in the Southeastern United States,

that provides a continuum of care for individuals with TBI, were

contacted by the project coordinator. The project coordinator, a

Recreational Therapist at the rehabilitation hospital, screened all

individuals interested in the study using the Six-Item Screener

(SIS) to assess cognitive status in order to determine eligibility

for a program or intervention [28]. The SIS has been used as a

screener into yoga studies for individuals with TBI [20]. After

screening the individuals, the project coordinator reviewed the

inclusion and exclusion criteria with the individuals with TBI as

well as their caregivers, to determine if they met the inclusion and

exclusion criteria for the study. Inclusion criteria for persons with

TBI required that they:

I. Had diagnosis of moderate-to-severe TBI, verified by the

individual’s Glasgow Coma Scale score upon admission to the

rehabilitation hospital [29],

II. Were a fluent speaker of English, by self-report,

III. Were 18 years of age or older,

IV. Were able to move into different seated, standing,

and supine postures without assistance (based on self- and

caregiver-report),

V. Had a caregiver that was willing to assist with participant

transportation needs throughout the study, and

VI. Had sufficient cognitive status to participate, as

determined by a score of at least 4/6 on the Six-Item Screener.

The presence of any one of the following criteria resulted in

exclusion from the study:

A. were unable to attend 12 or more yoga classes during the

eight-week intervention,

B. had current drug or alcohol abuse, per self-report, and

C. enrollment in another intervention study that could

affect sleep or mood. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were also

established for caregivers of participants with TBI to ensure

they were able to fulfill the role of caregiver throughout the

study, although a caregiver was only required if the individual

with TBI needed assistance with daily tasks.

Inclusion criteria for the caregivers required that individuals:

a. were age 18 or older,

b. had no prior history of TBI,

c. were the self-identified caregiver of person with TBI,

d. were a fluent speaker of English, per self-report, as being

willing to transport participant to all yoga sessions related to

the study (as needed).

Exclusion criteria for caregivers of people with TBI were as

follows:

i. were unable to report on participant for whom they

provide care, and

ii. had current drug or alcohol abuse based on self-report.

All participants provided written informed consent prior to the

start of the study. Participants admitted to the study were given

a $25 incentive, funded by the rehabilitation hospital research

department for clinician research projects, upon completion of

the study.

Intervention

Yoga sessions were conducted in groups in a yoga room within

a large rehabilitation hospital in the Southeastern United States.

Sessions occurred twice a week for eight weeks, for a total of 16

yoga sessions. A recreational therapist who is a yoga teacher and

specializes in yoga for individuals with TBI taught all yoga sessions.

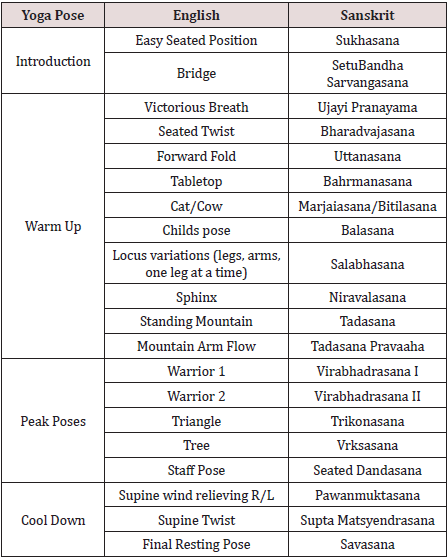

The sequences of yoga poses were designed based on the Love

Your Brain (LYB) Foundation yoga program, which is designed for

individuals with TBI [30]. The project coordinator of this study

adapted the LYB yoga sequences to fit this specific study group

[31], to focus on influencing sleep and mood. Changes to the LYB

protocol included increased time for meditation and a decrease

in poses accomplished on hands and knees. See Table 1 for yoga

sequence. Each yoga class was one hour long and included a

15-minute centering and focusing of the mind, 30 minutes of gentle

physical yoga postures in supine, prone, seated, and standing

positions, and 15 minutes of meditation and relaxation. The yoga

sessions remained at the same level of difficulty from start to finish,

in order to facilitate the transition from the rehabilitation setting to

the community setting by encouraging growth towards mastery of

the postures as opposed to growth in the number of postures.

Data Collection

Quantitative measures were chosen to focus on sleep and mood

for individuals with TBI. Qualitative data were collected through

post-intervention focus groups. The primary researcher conducted

all data collection.

Quantitative Measures

Sleep quality was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep

Quality Index (PSQI), a self-report questionnaire used to assess

the quality of sleep over a one-month period [32]. The 24-items

inquire about sleep duration, sleep medication, sleep latency,

sleep quality, and how sleep effects an individual’s daytime activity

[33]. An individual may be diagnosed with poor sleep if he or she

has a global PSQI score of greater than five. The PSQI has been

used to screen for insomnia in individuals with TBI in post-acute

care [34]. The PSQI has a diagnostic sensitivity of 89.6%, and a

specificity of 86.5% when differentiating between individuals who

experience ‘poor’ or ‘good’ sleep [32]. Depression was measured

using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 was

developed based on the DSM-V criteria of depression [8] and can be

self-administered [35]. The PHQ-9 is a nine-item depression scale

that measures level of depression over the past two weeks using

four-point likert responses, where 0=not at all, to 3=nearly every

day [36]. Once completed, the total score was summed to assess

level of overall depressive symptoms. The PHQ9 classifies level

of depression based on the sum of responses, with 0-4=minimal

depression, 5-9=mild depression, 10-14=moderate depression,

15-19=moderately severe depression, greater than 20=severe

depression [37], and a score greater than 12 is the cutoff for being

diagnosed with major depressive disorder [38]. The PHQ-9 was

also effectively used in a study on combat-related TBI [39].

Anxiety was measured using the Generalized Anxiety

Disorder-7 (GAD-7) survey. The GAD-7 is a seven-item anxiety

scale that measures level of anxiety of the past two weeks using

four-point likert responses, where 0=not at all, to 3=nearly every

day [40]. This self-report questionnaire has shown reliability and

validity [40,41] and can be used to analyze anxiety in the general

population [41]. The GAD-7 classifies level of anxiety based on the

sum of responses, with 0-4=minimal anxiety, 5-9=mild anxiety,

10-14=moderate anxiety, 15-21=severe anxiety, and a score greater than

10 is the cutoff for being diagnosed with generalized anxiety

disorder [40]. The GAD-7 was validated in primary care facilities

[36] but has also been used to measure anxiety in a study on

sleep and psychological conditions after sustaining TBI [42] and

used to measure anxiety related to mild TBI related to combat

[39]. Adjustment was analyzed using Part B of the Mayo-Portland

Adaptability Inventory (MPAI-4). The MPAI-4 has four parts, each

of which address a different aspect of adjusting to injury. Part B was

selected due to the specific focus on adjustment to injury related

to an individual’s mood (irritation, aggression, pain, depression,

anxiety, fatigue, social interaction, self-awareness, and sensitivity to

symptoms). The rating scale ranges from 0-4, from 0=no problem

to 4=severe problem that interferes with activities more than 75%

of the time [43]. A sum score of 0-7= mild limitations, 8-15=mild

to moderate limitations, 16-24=moderate to severe difficulties, and

>25=severe limitations with a score of less than seven indicating a

good outcome [44]. This scale was designed to assist in the clinical

evaluation of participant adjustment during the post-acute (post

hospital) period following an acquired brain injury [13]. This

scale has been used in multiple rehabilitation settings, including

post-acute rehabilitation, comprehensive day treatment, and

community-based rehabilitation [45-47].

Qualitative Data Collection. As a convergent mixed methods

study, this intervention was best examined through multiple

forms of data, addressing research questions in a general and

broad quantitative fashion, as well as providing a narrative and

explanatory qualitative aspect [48]. The participant focus group

focused on the participant’s experience in the yoga intervention,

giving an account of their experience, any change they noticed

in sleep, depression, anxiety, or adjustment to injury, and any

additional comments they had about the influence of yoga over

the past eight-weeks. The caregiver focus group facilitator asked

similar questions and focused on the caregiver’s observation of

participant behavior over the past eight-weeks. These focus groups

were held in the private yoga room at the rehabilitation hospital

and recorded using two audio recorders.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographics,

which included age, gender, marital status, race, work status,

education, time (in years) since injury, and cause of injury.

Nonparametric analysis was indicated because of the low sample

size; thus, the Friedman Test was used to compare mean ratings

of each assessment, using the Statistical Package for the Social

Sciences (SPSS) software version 24. Comparisons were made

between the group mean Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

scores, depression scores (PHQ-9), anxiety scores (GAD-7), and

adjustment scores (MPAI-4, Part B) from pre, mid, and postintervention

assessments. To further examine the quantitative

results using the means from each assessment, percent change was

calculated using the following formula:

Pre-intervention = [(post-intervention value–pre-intervention

value)/pre-intervention value] x 100%.

Qualitative Analysis

The qualitative focus groups were transcribed verbatim to

increase descriptive validity [49], and participants and caregivers

were assigned a subject number to ensure confidentiality.

The project coordinator observed the focus groups to ensure

interpretive validity [49], reporting that the project coordinator

and primary researcher shared the same perceptions of the focus

group discussion. After initial transcription, the primary researcher

reviewed the qualitative data for themes, and categorized the

responses based on their connection to sleep, depression, anxiety,

and adjustment to injury. The project coordinator and an additional

researcher reviewed the transcripts from the focus groups before

and after analysis to check for consistency and establish interrater

reliability [50]. In accordance with Creswell and Creswell’s

sequential process of qualitative analysis [50], focus group

transcriptions were organized and read thoroughly by the primary

researcher. Coding was deductive, to identify patterns within the

data relevant to predetermined outcomes (i.e., sleep and mood),

and to determine the existence of any emergent codes.

Mixing Quantitative and Qualitative Data

Qualitative and quantitative data were collected and analyzed

separately [50]. After individual data analysis, quantitative and

qualitative data were compared to discover converging or differing

results [48].

Results

Overall, 15 people were contacted and invited to participate

in eight weeks of yoga. Ultimately, seven people passed the SIS,

met the inclusion criteria, and committed to the study, while eight

declined despite having passed the SIS, citing scheduling conflicts,

distance from home, lack of interest, and inability to commit to

eight sequential weeks. Six people completed the study, five of

whom had caregivers, while one person dropped out of the study

1.5 weeks prior to completion due to travel conflicts. Of the six

participants who completed the study, four (67%) were female, and

the average age was 31, with the ages ranging from 21-43 years

old. The majority of participants were White (66%), and most were

single (83%). Half of participants had a graduate degree, although

50% were unable to work. The average time since injury was 4.67

years. On average, participants attended 14 of the 16 sessions,

with an attendance rate of 89% based on total number of sessions

offered. See Table 2 for additional participant demographics. In

the following sections, both quantitative data and qualitative data

are provided by outcome, as the intent of this convergent mixed

methods design was to compare converging or differing results

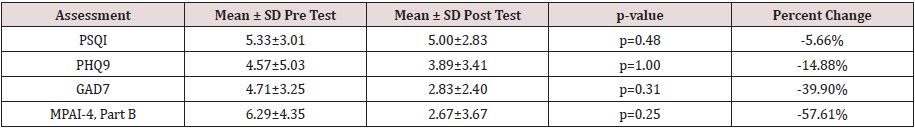

[48]. See Table 3 for the mean pre and posttest, p-value, and percent

change.

Sleep

The Friedman Test revealed that quality of sleep did not differ

significantly when comparing pre-, mid-, and post-intervention

PSQI scores (X2=1.46; p=0.48). The percent change from the preand

post-intervention scores yielded a result of -5.7% change,

indicating a minor decrease in reported issues related to sleep. The

qualitative data on sleep was convergent with the quantitative data,

supporting that there was no significant change in sleep quality for

most participants. Most caregivers and participants commented

on an improvement in sleep since the individual sustained the

injury, but most did not identify further improvement as a result

of the yoga intervention. However, one caregiver believes yoga

has enabled her loved one to have deeper rest while sleeping. The

caregiver stated that her loved one has “deeper sleep, she sleeps

longer in the morning, has trouble to wake up, and she dreams.

And she remembers her dreams!” In addition, one participant

commented on her ability to sleep, saying sleeping in the past year

“I would hear any little noise, it’d just bother me and wake me. So,

sleep with earplugs, I slept with earplugs and an eye mask for light.

Now I’m much better and I don’t need earplugs or a mask.”

Depression

The quantitative and qualitative data showed converging results

regarding depression, as neither form of data collection identified

substantial changes following the yoga intervention. The Friedman

Test showed insignificant results regarding pre-, mid-, and post-

PHQ-9 data (X2=0, p=1.00), while the percent change from the preto

post-intervention assessment was -14.9%, indicating a slight

decrease in depression. Depression was briefly highlighted in the

participant focus group, as one individual stated “I’ve never seen

myself as depressed,” and later said “I don’t think I’m depressed

but again, the doctors have attributed my past tiredness and

sluggishness to depression, and they say that now that I am active,

it helps that aspect.”

Anxiety

No significant difference in anxiety was found using the

Friedman Test (X2=2.33, p=0.31). However, the percent change from

pre- to post-test was -39.9%, representing a substantial decrease

in anxiety after the yoga intervention. Complementing the percent

change calculation, both caregivers and participants provided

meaningful comments related to a decrease in anxiety during

focus groups. Caregivers stated that yoga was “calming,” “relaxing,”

and “increased the awareness” of their loved ones. Participants

shared similar thoughts, using the words “calming” and “relaxing”

throughout their discussion of their yoga experience. One caregiver

stated: What my daughter seems to get out of it more than anything

is the mindfulness and the meditation and just calming her down.

Because we go at a high pace, and so this is a good way for her to just

relax and help her brain get better. In addition, another caregiver

said “she’s maybe more relaxed I would say. Less anxious.” Later

on, this same caregiver explained, that yoga “sets her back and

somehow it’s relaxing in order to let other things than the panic

in her mind.” Participant responses aligned with the caregiver

perspectives, as participants commented, “yoga has always relaxed

me,” and “it helps me loosen up.” Another participant expressed

her appreciation of yoga, saying: It’s perfect how the practice slows

down, repeats, and just focuses on just a healthy mind. So, whereas

out in the world, we’re supposed to go, go, go. Here we can just slow

down, be in our minds, be present, and just be.

Adjustment

Though quantitative data regarding adjustment to injury

produced non-significant findings based on the Friedman Test

(X2=2.80, p=0.25), the calculated percent change from the preto

post-intervention MPAI-4 Part B assessment was -57.6%,

indicating a considerable decrease in issues related to adjustment

to injury. In addition, the qualitative data showed an improvement

in adjustment. Qualitative data showed an increased interest in

activity and self-esteem, as well as a decrease in irritability from

the perspective of both the caregivers and the participants. When

asked about a change in amount of activity for individuals with TBI,

one caregiver said, “he’s interested in doing more than just this.”

When asked the same question, a participant stated, “I do want to

do more activities outside of the house.” Moreover, one participant

explained, “I do have more endurance of being able to take on more

activities throughout the course of the day.” Caregivers emphasized

an increase in self-esteem following the yoga intervention. One

caregiver commented on the relationship between improvement in

self-esteem, and the eight weeks of yoga, saying:

Self-esteem I think is a big problem. I mean, a huge problem.

But um, maybe for the past two months she, I think she’s more

aware and more in acceptance. So, it seems like the self-esteem is

less of a problem.

While another caregiver explained that her husband is

considering taking initiative on a project that she relates to

an increase in self-esteem. Concerning irritability, a caregiver

stated her son is “definitely getting more pleasant to be with,”

and a participant said “yoga, being mindful, the whole practice of

presence and really being intentional and present with what you’re

doing has positively affected the way I approach anything.” Social

Support in the TBI Community. Though not included in the purpose

of this study, appreciation of the community that formed as a result

of the yoga intervention was evident as a theme throughout the

caregiver and participant focus groups. In the profound words of

a caregiver, yoga has provided “a place [for the participants] to

be injured.” Caregivers expressed “it’s just nice to be with people

who are maybe dealing with the same things,” “they need groups

to socialize, to exchange because they’re very lonely,” and yoga has

“been wonderful for him because the rest of the time he is in the

home alone.” In line with caregiver responses, a participant stated

that yoga helps in “having community support others who know

your situation, experience, having gone through the same things.”

One participant expressed an appreciation of the ability to share

experiences, saying “it’s better to have friends that you can meet

actually, all of you, and to know that they’re doing the same thing

that you have to.” The community developed through yoga is unique

due to the emphasis on rest and relaxation, which one caregiver

highlighted by saying “yoga allows them to have time to think…

we’re not the ones that are gonna settle down with them like ‘ah,

let’s rest’…we don’t have the time and probably not the patience

either.”

Discussion

The primary purpose of this pilot study was to examine the

influence of yoga on individuals TBI related sleep quality and mood

after eight weeks of bi-weekly yoga. There was not a substantial

change in sleep based on the PSQI. The data in this study differ

from previous research that found yoga to improve sleep [19,51].

Though sleep disorders are common for individuals with TBI [7],

the majority of this study population did not express complaints

with sleep prior to or after the yoga intervention, resulting in

little to no change in quantitative and qualitative results related

to sleep. Considered to be a residual effect of sustaining TBI [52],

depression was expected to be present in this study population.

The pre-intervention average depression score from the PHQ9 was

4.57, (just beneath the mild depression score of 5-10), showing

that participants did not initially experience significant depression

symptoms. Depression was not significantly impacted by the yoga

intervention, though the percent change showed a slight reduction

in depressive symptoms, consistent with previous research

claiming yoga yielded decreased reports of depression [53].

The findings of this study support previous work that yoga has

the potential to decrease symptoms of anxiety [7,16,54]. Though

quantitative measures yielded insignificant results, the percent

change showed a substantial decrease in symptoms of anxiety. The

qualitative data also demonstrated a reduction in anxiety, which

participants identified was due to the emphasis on the calming

and relaxing effect of yoga. Furthermore, a study by Verma et al.

identified a decrease in anxiety continued beyond the yoga session

was supported by caregiver and participant perspective shared

during the focus groups [7].

Although not statistically significant, adjustment to injury did

substantially improve, as indicated in the percent change calculation

and the qualitative data. In congruence with the claim that yoga

contributes to overall adjustment for individuals with TBI [55], this

yoga intervention contributed to a decrease in irritability, and an

increase of interest in activities. In addition, focus group discussions

showed considerable improvement of self-esteem and selfawareness,

supporting previous work that demonstrated the ability

to improve emotional awareness through yoga after sustaining TBI

[56]. The yoga intervention focused on awareness of the body and

the mind by encouraging participants to bring awareness to specific

body parts at time and acknowledge certain emotions that may

come up. The focus on awareness throughout each yoga session

likely contributed to the comments on increased self-esteem and

awareness, consistent with the study results on the impact of an

8-week yoga program for individuals with TBI that indicated an

improvement in self-perception [57]. A theme of social support

through the yoga intervention became apparent through the focus

group discussions. In a study on social support for individuals with

TBI, Stålnacke [58] found reports of low-quality social support due

to lack of social interaction. Consistent with results from other yoga

studies [59-62], caregivers and participants described the yoga sessions

as beneficial due to the sense of camaraderie with people

who have similar life changes due to sustaining TBI. Caregivers

expressed the need for their loved ones to be with other people due

to their loss of friends since sustaining TBI. Discussions during both

caregiver and participant focus groups indicated an appreciation of

the shared experience yoga provides. Participants in an inpatient

rehabilitation setting benefited from the social interaction provided

by yoga [21] supporting the theme of social support that emerged

from this pilot study.

Implications for Further Research and Practice

The diverging results from quantitative measures and

qualitative interpretations specific to the influence of yoga on

sleep and mood indicate a need for further investigation. In order

to expand this study, future research should consider including

only those with current complaints related to sleep and mood

and involve a larger sample size. Future studies may also consider

the use of a yoga sequence that becomes progressively more

challenging, as the content of the yoga intervention used in this

study maintained the same level of difficulty from start to finish.

A progression of poses may produce more substantial results, as

challenging activities are more likely to produce change [63]. Yoga

is a valuable therapy that can be implemented in a rehabilitation

setting [21,23,64]. Attendance was high due to the location of the

yoga intervention, since the rehabilitation hospital was a familiar

place to all participants. Participants and caregivers also stated that

they would like to see yoga included in TBI rehabilitation and they

also identified the desire for the yoga intervention to continue and

be offered individuals in outpatient programs. The qualitative data

supported the value of yoga within a TBI rehabilitation setting as it

can decrease anxiety, improve adjustment to injury, and promote

social support within the TBI community.

Limitations

Due to the nature of research, this pilot study has limitations.

This study took place in one rehabilitation hospital in the

southeast and cannot be generalized to all yoga programs within

a rehabilitation hospital. Second, while we aimed to observe

the influence of yoga on ten people, only six people remained

committed to the study from start to finish, resulting in a small

sample size, where it is difficult to determine statistically significant

changes in outcomes. More clearly stating attendance requirements

when recruiting participants may increase commitment to the

study. This study was not blind to the primary researcher or the

participants, as the primary researcher was in direct contact with

the participants, and the participants were informed of the purpose

of the study when recruited for the study. Due to the pilot nature

of this study, no control group was observed in comparison with

the individuals receiving the yoga intervention. By adding a control

group, researchers may be able to further understand the influence

of yoga versus other environmental and social influences. Finally,

the yoga sessions were not designed to build on themselves, but

rather involved the same primary moves with variations according

to the yoga instructor’s preference. A yoga sequence that becomes

progressively more challenging may yield stronger results.

Acknowledgement

For more Complimentary & Alternative Medicine Open Access Journal articles Please Click

To Know more Open Access Publishers Click on Lupine Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublisher

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.