Alcohol-related intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious public

health issue which has attracted a lot of research and debates. While

some studies have reported the relationship between alcohol and IPV to

be linear, others have reported threshold effects. While some studies

have found the link to be strong, others have reported weak or no

association. Using Logistic regression and meta-analysis, the

relationship, strength of relationship and possible moderators of the

alcohol-IPV link are investigated in ten sub-Saharan African countries.

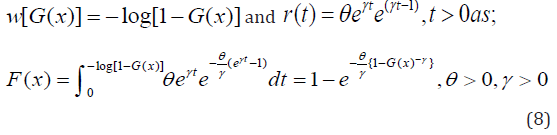

The results indicates that while alcohol consumption is associated with

IPV in three of the countries, alcohol abuse was associated with IPV in

the other seven countries lending support for both the linear and

threshold effects in sub-Saharan Africa. The meta-analysis showed a

strong association between alcohol and physical IPV while a weaker

association was observed for the alcohol- sexual IPV link. Moderator

analysis showed that the strength of the alcohol-IPV link in sub-Saharan

Africa varies with wealth index, marital length, and marital status,

and jealousy, place of residence and justification of the use of

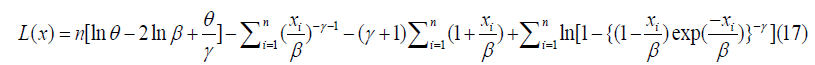

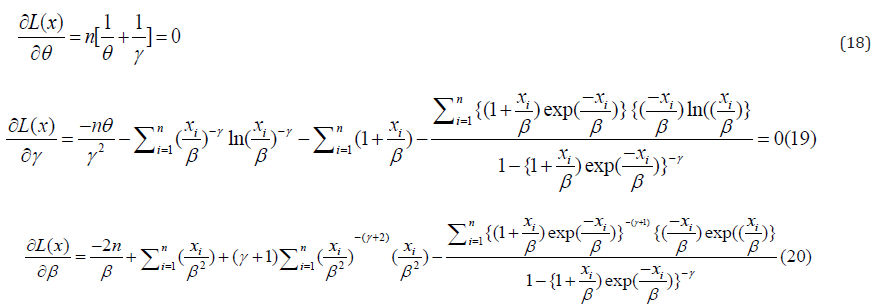

violence. The nature of moderation was different between countries. The

results of this study can be applied to plan country specific and

multi-faceted intervention programs.

Keywords: Alcohol; Intimate Partners; Violence; Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as any physical,

psy-chological or sexual harm that is caused by the actions of a present

or previous intimate partner [1]. It a major public health issue and

violates women's human rights [1]. Cross sectional studies have shown

that 10-69 per cent of women of reproductive age experience physical

violence at least once in their lifetime while 6-59% report an attempt

or actual sexual violence by their intimate partners [2]. Intimate

partner violence takes place in all backgrounds and among all

socioeconomic, religious and cultural groups with women bearing the

global burden [1]. Prevalent rates are different across countries with

rates between 11-52% in developing coun-tries [3]. IPV has been reported

to lead to physical injuries, loss of pregnancy and complications

during pregnancy [2]. It can also result in emotional problems such as

depression and suicide [2] and victims have been reported to resort to

use of drugs and alcohol as a means of coping with the abuse [4].

Several risk factors such as young age, low education, occu-pation,

experiencing parental violence, drug and alcohol use, con-trolling

behaviour by the husband [5], justification of wife beating [6] and so

on has been reported to increase the odds of IPV; of these, alcohol

consumption has been consistently implicated [2,7] with the prevalence

of alcohol-related IPV differing in diverse countries [2]. Although an

association between alcohol and IPV has been established in previous

studies, there are arguments on the role of alcohol in IPV, the effect

of alcohol and the strength of the association between alcohol and IPV.

Although alcohol-related IPV is a widely researched topic, only some

research has been done in sub-Saharan Africa [8,9] and none has

investigated the magnitude of the association across countries in

Sub-Saharan Africa. The aim of this study was to determine the type of

association between alcohol and IPV in sub-Saharan Africa and also

examine the strength of the relationship between alcohol and IPV in

Sub-Saharan Africa.

Methodology

For the quantitative study, secondary analysis and meta-analy-sis

were used to analyze cross-sectional data from the demographic and

health surveys of ten countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Burkina Faso,

Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Prin-cipe,

Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe). Since the aim of this re-search was to

determine the relationship between alcohol and IPV in sub-Saharan

Africa, a quantitative research design was adopted because it is an

appropriate method for showing associations and quantifying

relationships between variables [10]. In order to examine the

relationship and moderators of the alcohol-IPV link in sub-Saharan

Africa, a secondary analysis of previously conducted primary studies of

ten countries in sub-Saharan Africa was carried out. This is the method

of choice for this research as it takes a cross national perspective

which requires that data from several countries in sub-Saharan Africa be

analysed. Data sets for this study were also easier to access and raise

little or no ethical issues as re-spondents are already made anonymous.

Data Collection Methods

This study did not collect primary data but accessed data of the

demographic and health survey of ten sub-Saharan Africa countries

(Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Nigeria, Sao Tome and

Principe, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe). Large sample sizes were used

with high response rate thereby ensuring that statistically significant

relationships are detected. Access to the data sets was gained by

requesting permission from Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). Approval

from DHS was granted by email. Data was identified using the domestic

violence questionnaire. The identified data sets were downloaded to the

researcher's personal computer using SPSS (version 19) software.

Variables in the study were identified using the DHS recode manual.

Sample/Sampling Strategy

This study used quota sampling to identify DHS surveys con-ducted

between 2006 and 2011 made available by 2012 in sub-Sa-haran Africa. For

this research, only countries from sub-Saharan Af-rica were included

because the main independent variable (alcohol consumption) was not

measured in North African countries as con-sumption is prohibited. The

data for each country was the most re-cent. This was to ensure that

results reflected the current strength of the alcohol-IPV link and that

recommendations are made based on current evidence. All datasets

included asked questions on domestic violence and covered the topic of

alcohol consumption and frequency at which husband/partner gets drunk

because of the fact that the focus of this study is on alcohol-related

IPV.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS (version 19.0) and Revman Meta-analysis software.

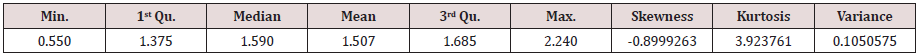

Univariate Analysis: Frequencies were used to determine the prevalence of the different forms of IPV, alcohol consumption

and alcohol related IPV in the ten countries included in this study.

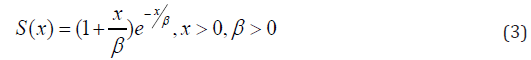

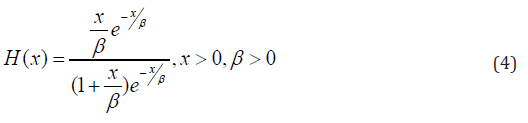

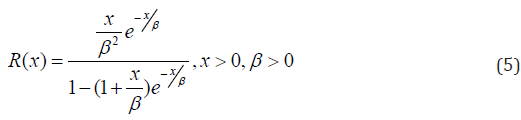

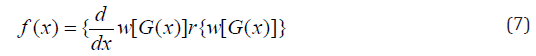

Logistic Regression: In order to determine the type of

relationship between alcohol and intimate partner violence in

sub-Saharan Africa, a logistic regression of the four category alcohol

measure was carried out by comparing non-drinkers to drinkers (drinkers

who never got drunk, who got drunk sometimes and those who got drunk

often). Results are reported as B (Standard Error), odd ratios (OR) and

95%CI for OR. A significant Wald test p-value indicates a significant

difference between the categories and non-drinkers.

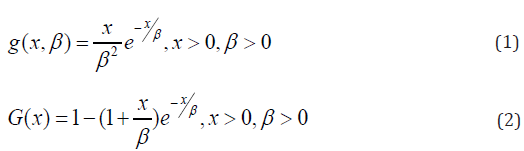

Meta-Analysis: In order to investigate the strength of the

alcohol-IPV link in sub-Saharan Africa, a meta-analysis was car-ried out

using the Revman software. This was done by comparing non-abusers

(non-drinkers and drinkers who never got drunk) and abusers of alcohol

(husbands who got drunk sometimes and often). Based on the assumption

that effects may vary across samples and studies [11], random effects

model was used. The random effects model was used in this study because

of the heterogeneous nature of the studies and because this model

generates results that are generalisable to the sub-Saharan Africa

population. The heteroge-neity of the result was investigated using the

Cochran's Q test [12]. A significant I2 shows heterogeneity among

included studies with higher values indicating increased differences

within study [12]. Due to the high heterogeneity between countries

included in the meta-analysis, further moderation analysis was carried

out.

Hierarchical Logistic Regression: Using the method described

by Field [13], hierarchical logistic regression was used to study the

moderator effects of the independent variables on the al- cohol-IPV

link. In order to account for the complex sampling used in the DHS

survey, the probability of being administered the domestic violence

questionnaire and to adjust for the probability of non-re-sponse [14];

all analyses were conducted using the domestic violence sample weight.

Ethical Issues

One of the ethical issues with conducting a secondary data anal-ysis

is the permission to access datasets. Approval was sought by the

researcher and access was granted. The DHS also operate a no data

sharing policy. To ensure data protection, memory sticks and computers

were password protected to guard against unauthorised access. It is also

important to confirm that the data obtained from the primary study was

ethically obtained. The primary DHS study was done with the informed

consent of the subjects and confidenti-ality obtained with the National

ethics committees of the different countries approving the surveys.

Furthermore, the datasets have been made anonymous by removing all

identifier information.

Results

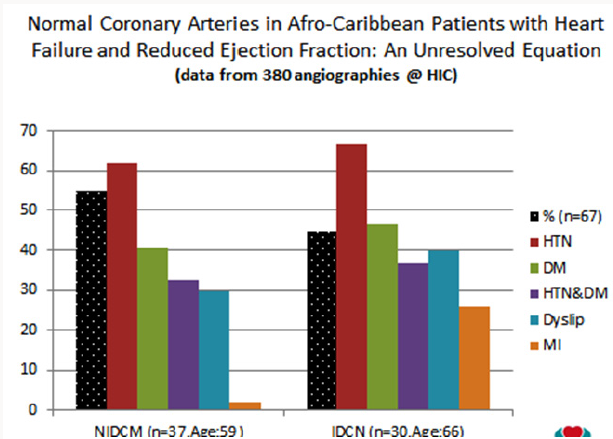

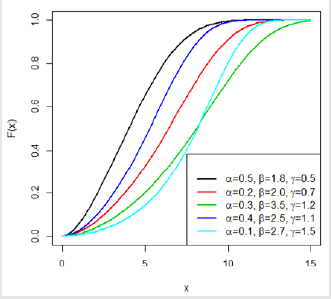

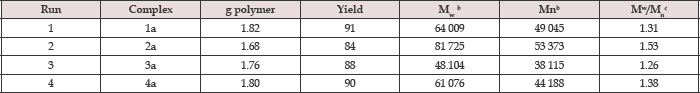

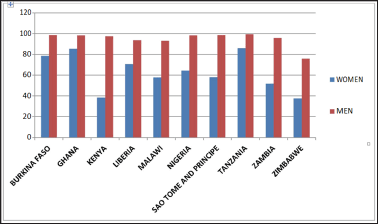

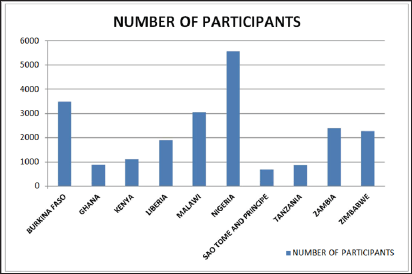

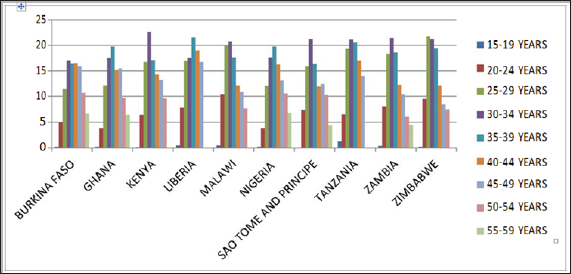

The study population consisted of women aged 15-49 years old and men

aged 15-59 years old in ten countries in sub-Saharan Af-rica. Six

hundred and eighty-two couples were interviewed in Sao

Tome and Principe, 873 in Tanzania and 883 in Ghana. The largest numbers

of 5566 couples were included in Nigeria while 3488 and 3051 couples

participated in Burkina Faso and Malawi respectively (Figure 1). Of

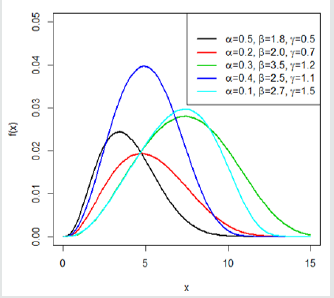

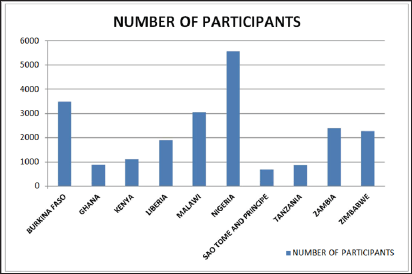

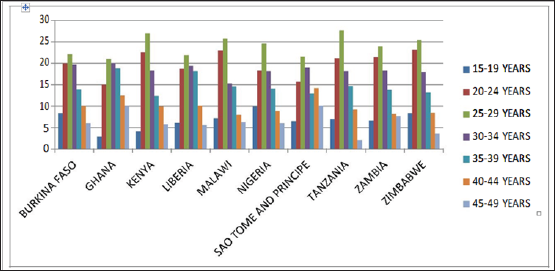

these numbers, the highest percentage of women were in the 25-29 years'

age group with this group accounting for 22.1% of the women in Burkina

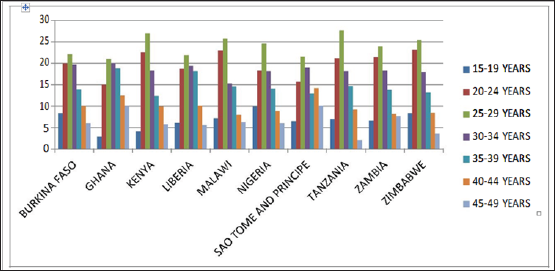

Faso, 27% in Kenya, 25.8% in Malawi and 27.7% in Tanzania. For the men,

22.6%, 20.8%, 21.3% and 21.4% were in the 30-34 years' age group in

Kenya, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Zambia respectively. In Ghana (19.8%),

Liberia (21.5%) and Nigeria (19.8%), the highest proportion of the male

participants were in the 35-39 years’ age group (Figures 2a & 2b).

Figure 1: Number of Participants in the Study.

Figure 2a: Age group of the Women

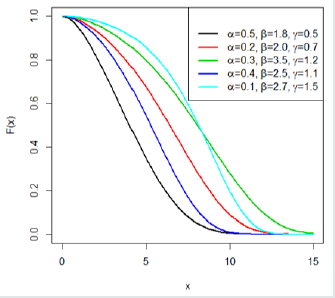

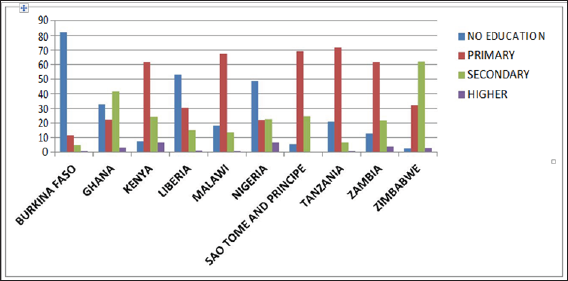

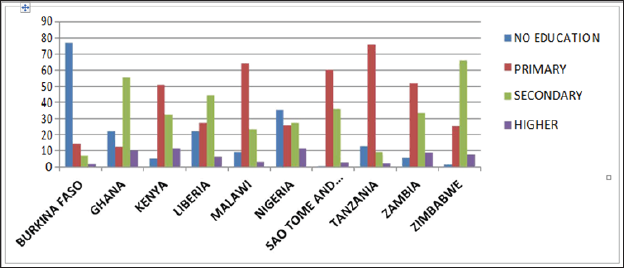

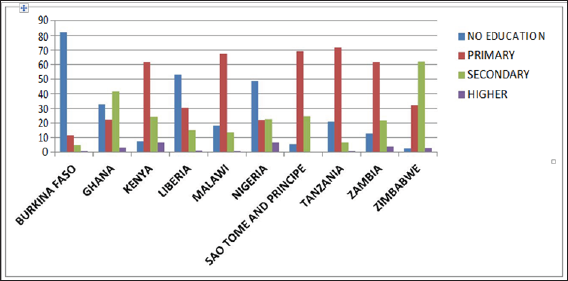

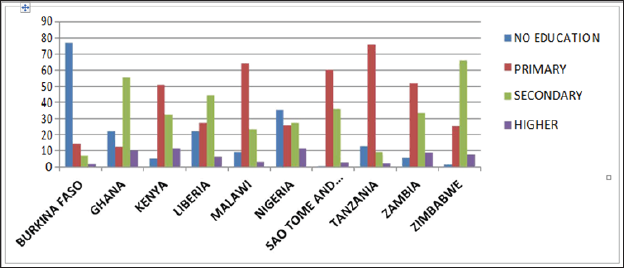

In Burkina Faso, 82.3% of the women had no education compared to

77.0% of the men. Zimbabwe and Sao Tome and Principe were found to have

the highest number of couple who have had any form of education with

94.2% of the women and 99.4% of the men having a primary, secondary or

higher education in Sao Tome and Principe. In Zimbabwe, only 2.7% of the

women and 1.2% of the men have had no education at all. 5.2% of the

women in Burkina Faso and 6.6% of the women in Tanzania reported having a

second-ary education compared to 41.5% and 62.1% in Ghana and Zimbabwe

respectively (Figures 3a & 3b).

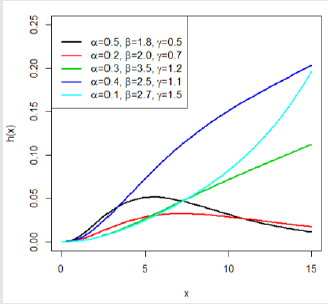

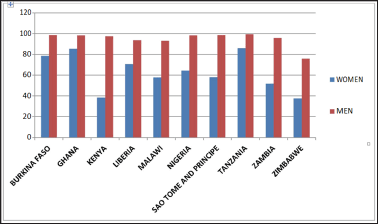

Employment Status

Highest proportions of women who are unemployed were in Zimbabwe,

Kenya, Zambia and Malawi with 62.3%, 61.6%, 48.3% and 42.3% of the women

reporting that they have no paid employment respectively. The highest

number of women who were em-

ployed was reported in Ghana (88.5%), Tanzania (86%), Burkina Faso

(78.6%) and Nigeria (64.4%). For the men, the highest rate of

unemployment was in Zimbabwe (24.2%), Malawi (6.9%) and Liberia (6.3%)

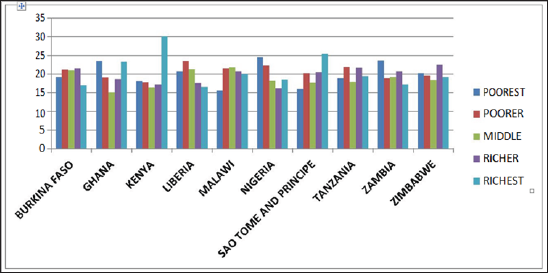

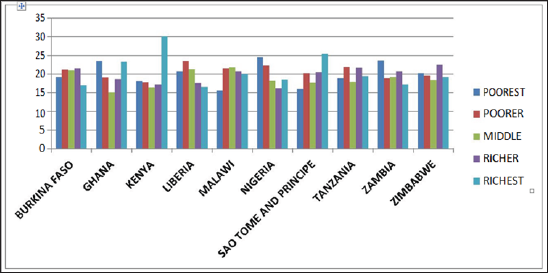

(Figure 4). When wealth index was considered, Figures 5 show that 24.5%

and 22.3% of Nigerians in the study population were in the poorest and

poorer wealth indexes respectively. Kenya, Sao Tome and Ghana have the

highest percentages of 30.2%, 25.4% and 23.4% of the couples in the

richest wealth index while 21% of the couples in Burkina Faso, 21.4% in

Liberia, 21.9% in Malawi and 19.2% in Zambia were in the middle wealth

index.

Figure 2b: Age Group of the Men.

Figure 3A: Education Level of the Women.

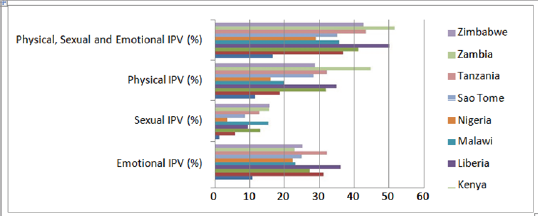

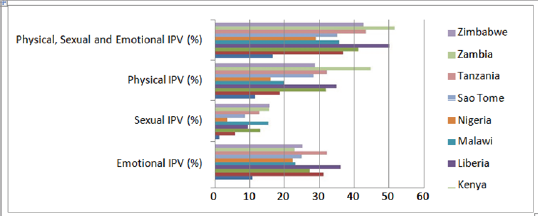

Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence

The prevalence of emotional IPV was lowest in Burkina Faso (10.8%)

and highest in Liberia (36.3%). In Ghana, 31.4% of the women reported

experiencing emotional IPV while 32.3% reported same in Burkina Faso.

The percentage of emotional IPV is closest in Sao Tome and Principe and

Zimbabwe with 25% of the women reporting emotional IPV in Sao Tome and

Principe and 25.2% in Zimbabwe. The percentage of women who reported

sexual IPV ranged from as low as 1.2% in Burkina Faso to as high as

15.8% in Zimbabwe. Figures in Zambia and Malawi are closest to Zimbabwe

with 15.6% of the women in Zambia and 15.4% of the women in the study

population experiencing sexual violence from their husbands or partners.

Zambian women reported the highest prevalence of physical IPV (44.9%)

while the lowest percentage of reported physical IPV was 11.5% in

Burkina Faso.

Figure 3b: Education Level of the Men.

Figure 4: Employment Rate.

Figure 5: Wealth Index of Participants in the Study.

In Kenya and Liberia, 32% and 35% of the women reported physical IPV.

When all three forms of IPV were considered, prevalence rate was

highest in Zambia (51.9%) followed by Liberia (50.3%) and lowest in

Burkina Faso (16.7%). In general, the prevalence of physical and

emotional IPV were higher than that of sexual IPV indicating that women

are less likely to experience or report sexual IPV in sub-Saharan Africa

(Figure 6).

Figure 6: Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence in sub -Saharan Africa.

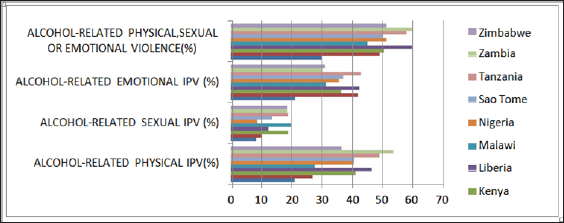

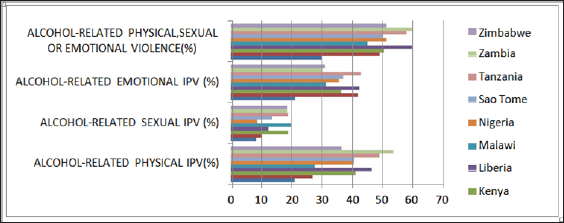

Prevalence of Alcohol-Related Intimate Partner Violence

Figure 7: Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence in sub -Saharan Africa.

Figure 7 shows the prevalence of alcohol-related intimate part-ner

violence among married and cohabiting women in sub-Saharan Africa. The

prevalence of alcohol related physical IPV was between 21.2 to 53.9% in

this study. The highest prevalence rate of alcohol-related sexual

violence was 19.9% in Malawi while the lowest prevalence of 8.8% was

reported in Nigeria. The prevalence of alcohol-related emotional IPV

ranged from 21.3% in Burkina Faso to 43.1% in Tanzania. When all three

forms of IPV were considered, prevalence rates ranged from as 16.7% in

Burkina Faso to as high as 51.9% in Zambia.

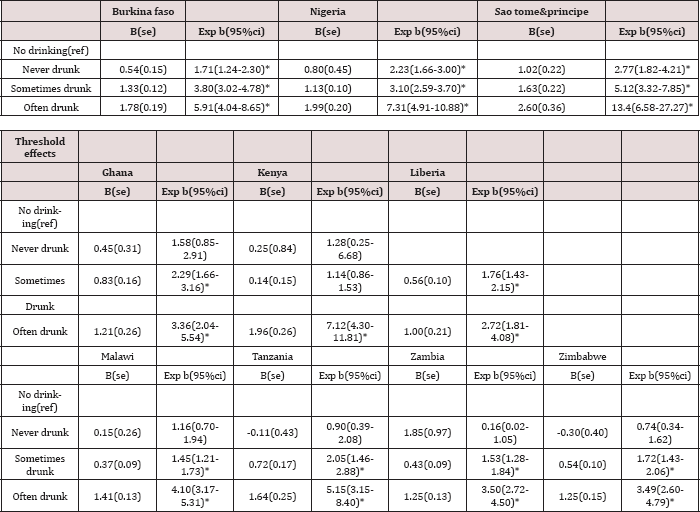

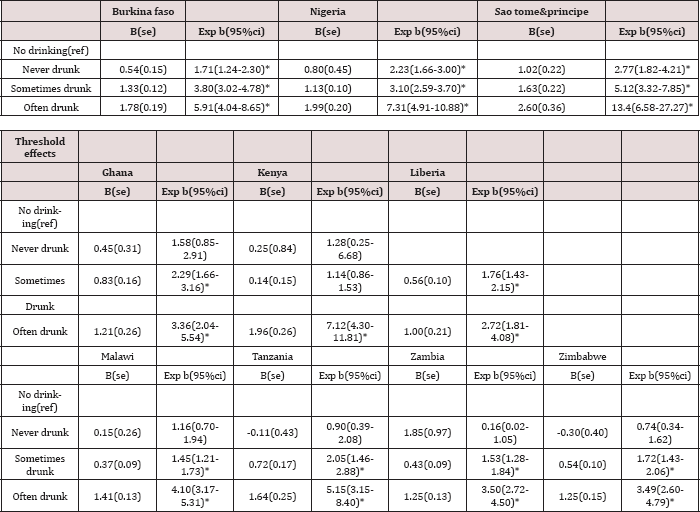

Relationship between Alcohol and Intimate Partner Vi-olence

The relationship between alcohol and intimate partner violence was

investigated by conducting a logistic regression of intimate partner

violence (physical, sexual or emotional IPV) and the four level drinking

variables. The significance of the effect of each level of the drinking

variable on IPV was assessed using the Wald's test. Odd ratios (Exp B)

with the 95% confidence intervals, standard error and Wald's test p

values are presented. In Burkina Faso, the odds of women experiencing

any form of IPV (physical, sexual or emotional IPV) is 1.7 times higher

in women whose husbands never got drunk than in women whose husbands

never drink while the odds of experiencing IPV is 2.23 (1.66-3.00) and

2.77 (1.82-4.21) greater in women whose husbands never got drunk

compared to women whose husbands never drink in Nigeria and Sao Tome and

Principe respectively. The Wald’s test shows that there is a

significant difference in the odds of experiencing IPV by women whose

husbands drink but never got drunk and women whose husbands never drink.

The results show that in Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Sao

Tome and Principe, alcohol consumption rather than alcohol abuse is

associated with intimate partner violence indicating that there is a

linear relationship between alcohol and IPV in these countries.

In Ghana, the odd of perpetrating intimate partner violence is 2.29

(1.66-3.16) in men who got drunk sometimes and 3.36 (2.04-5.54) in men

who got drunk often compared to non-drinkers. While the OR for

experience of intimate partner violence is 7.12 (4.3011.81) in women

whose husbands often abuse alcohol in Kenya, the OR for IPV by women

whose husbands often get drunk is 2.72 (1.81-4.08) in Liberia. In

Malawi, husbands/partners who get

drunk sometimes are 1.45 times more likely to abuse their partners

compared to men husbands or partners who do not drink alcohol while the

odds of perpetrating IPV is 4 times higher in husbands who get drunk

often. Wald's test p values showed that there is no significant

difference in the odds of women experiencing intimate partner violence

in women whose husbands drink but never got drunk and women whose

husbands never drink in Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia

and Zimbabwe. This indicates that it is alcohol abuse rather than

drinking of alcohol that is associated with intimate partner violence.

These full results are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1: The effect of alcohol on intimate partner violence in sub

The Strength of the Alcohol-Intimate Partner Violence Link in sub-Saharan

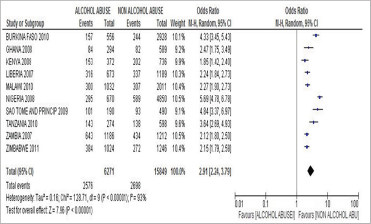

a. Effect of Alcohol on Physical Intimate Partner Violence

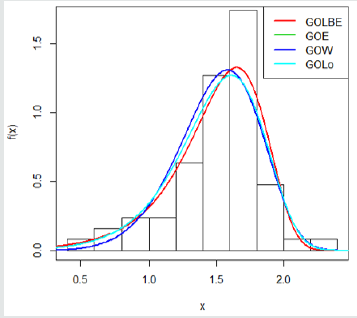

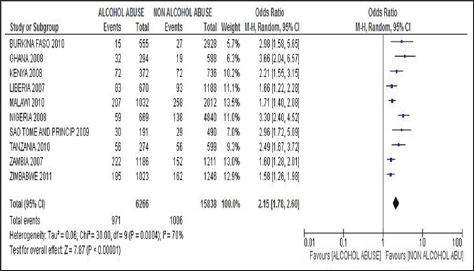

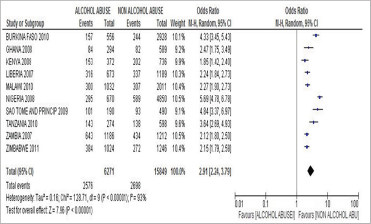

Figure 8 showed the result of the meta-analysis to determine the

strength of the alcohol-physical intimate partner violence in ten

sub-Saharan Africa countries. A total of 22,120 participants were used

in the study. Of these numbers, 6,271 were in the group of women whose

husbands drink abuse alcohol while 15,849 were in the group of were in

the group of women whose husbands/partners do not abuse alcohol. While

2,576 women reported experiencing physical intimate partner violence in

the first group, a total of 2,698 women reported physical IPV in the

other group. The results show the test for heterogeneity, I2=93%

indicating a high degree of heterogeneity between the ten countries

included in the analysis. The odds ratio is 2.91 (95% CI (2.24-3.79)

showing that there is a strong association between alcohol and physical

intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa. The overall effect Z

=7.96 and was statistically significant (p<0.00001). This indicates

that the strength of the alcohol-physical IPV link is strong in

sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 8: Effect of Alcohol on Physical IPV in SSA.

b. Effect of Alcohol on Sexual Intimate Partner Violence

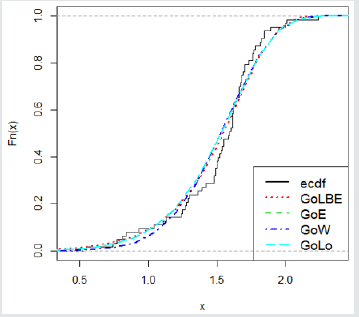

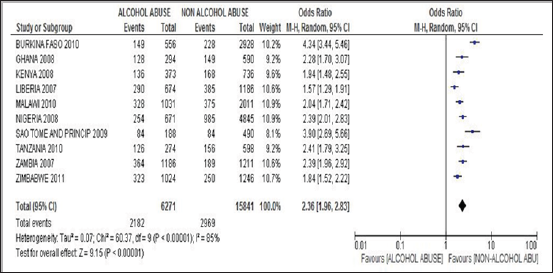

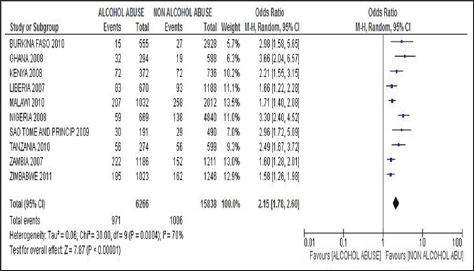

The meta-analysis to determine the effect of alcohol on sexual IPV is

presented in Figure 9. A total of 22,104 women were included in the

study. 6,266 were in the alcohol abuse group while 15,838 were in the

non- alcohol abuse group. Of the 6,266 women in the alcohol abuse group,

971 reported experiencing sexual IPV while 1,006 reported sexual IPV in

the non-alcohol abuse group. The above results show an I2 value of 70%

indicating heterogeneity between studies. An OR of 2.15

(95%CI=1.78-2.60) means that women in sub-Saharan Africa are two times

more likely to report sexual violence when their husbands/partners abuse

alcohol than when they do not. An odd ratio of 2.15 shows that there is

a small effect size for the alcohol-sexual violence link in sub-Saharan

Africa. The overall effect Z=7.87 (0.00001) is highly significant

indicating that the effect of alcohol on IPV is highly significant.

These results imply that the strength of the alcohol-sexual IPV link is

weak in sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 9: Effect of Alcohol on Sexual Intimate Partner Violence in sub-Saharan Africa.

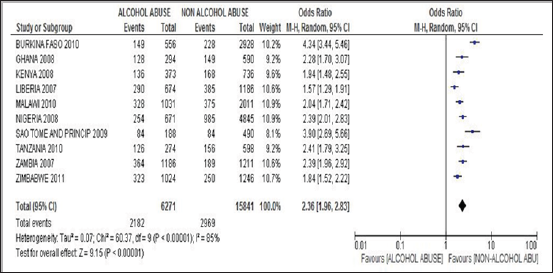

c. Effect of Alcohol on Emotional Intimate Partner Violence

A total of 22,112 respondents took part in the study to deter-mine

the effect of alcohol on emotional intimate partner violence. A total of

5,151 participants reported experiencing emotional intimate partner

violence. Of this number, 2,182 reported that their husbands abuse

alcohol while 2,969 reported that their husbands never abuse alcohol.

The result of the meta-analysis is presented in Figure 10 below. The

results above show that women whose husbands abuse alcohol are 2.36

times more likely to report emotional intimate partner violence in

sub-Saharan Africa OR=2.36 (95%1.96-2.83). This means that there is a

moderate effect size for the association between alcohol and emotional

intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa. An I2 value of 85%

indicates high heterogeneity between studies. The overall effect Z was

highly significant (Z=9.15, p<0.00001)

Discussion

Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence in SSA

In this study, the prevalence of physical intimate partner violence

is 44.9% in Zambia, 28.9% in Zimbabwe and 19.9% in Mala

wi. These values are similar to the 45%, 28% and 20% reported by Hindin

et al. [15] for Zambia, Zimbabwe and Malawi respectively. On the other

hand, the 32% and 32.2% prevalence rates reported for Kenya and Tanzania

herein are lower than the 39% reported by Hindin et al. [15] and the

48% observed by Tumwesigye et al. [16] for Uganda which is a neighboring

East African country. The percentage of physical IPV in other countries

in this study ranged from between 11.5% in Burkina Faso to 28.5% in Sao

Tome and Principe.

While some of these rates are similar to figures reported in other

sub-Saharan African countries, others are less. For instance, the 28.5%

prevalence reported here is similar to the 29% reported for Rwanda [15].

However, the 11.5% reported for Burkina Faso is lower than rates

reported anywhere in sub-Saharan Africa but similar to the 12% reported

for Haiti [3]. These differences in prevalence rates may be as a result

of the questions used to assess physical IPV.

Figure 10: Effect of Alcohol on Emotional Intimate Partner Violence in SSA.

This study asked respondents whether husband/partner has ever

threatened or attacked them with a gun/knife or other weapons while the

Hindin et al. [15] separated this question into threat and actual

attack. Combining these two questions would mean that women who have

experienced both threat and the act can only give one response to both

questions leading to the lower rates obtained in this study. In this

study, 16.1% of women in Nigeria re-ported physical IPV. This is

slightly higher than the 15% reported by Antai et al. [17] using the

same study data. While the Antai et al. [17] study used the individual

recode which is a sample of legally married women, the present study

used a sample of currently married/cohabiting women. This is consistent

with findings that the prevalence of IPV is higher in currently married

than legally married women [15]. In spite of these observed differences

in the prevalence of physical IPV in some sub-Saharan African countries

in this study, the observed prevalence of 11.5 to 44.9% in this study is

consistent with that reported in other studies [2,3,16-18].

Apart from physical IPV, the prevalence of sexual and emotion-al IPV

was also examined. Results indicated that the rates of sexual IPV ranged

from 1.2% in Burkina Faso to 15.8% in Zimbabwe. These rates are similar

to the 3 to 16% prevalence rates reported in existing literatures for

sub-Saharan Africa [15,17]. The prevalence of emotional IPV in this

study ranged from 10.8% in Burkina Faso to 36.3% in Liberia. This is

higher than the prevalence rates of 10.4 to 22.7% reported elsewhere

[19]. When all three forms of IPV were considered, the prevalence rates

increased for all ten countries and were higher than that reported in

previous studies. For example, Hindin et al. [15] reported a prevalence

of 45% for Zambia in their studies while this study shows a prevalence

of 51.9% for Zambia when all forms of IPV were considered. It can thus

be argued that studies investigating only one form of IPV result in an

under estimation of the magnitude of IPV. Overall, the prevalence of

sexual violence in this study was consistently lower than that reported

for physical and emotional violence across all countries included in

this work.

Prevalence of Alcohol-Related Intimate Partner Violence

The prevalence of alcohol IPV was between 29.9% to 60.1% when of

physical, sexual or emotional IPV is considered. These rates are higher

than the 33.9 to 49.5% reported for countries in sub-Saharan Africa

[15,16] and 10.5 to 55% reported elsewhere [2]. However, this is lower

than the 65% rate reported in South Africa [2]. The higher rates

reported in this study is as a result of the fact that this study

investigated the experience of all three forms of IPV indicating that

previous studies may have been subject to an under reporting of

prevalence rates of IPV as only physical or sexual IPV are usually

investigated. The lower prevalence of alcohol-related IPV in this study

compared to the 65% prevalence reported in South Africa can be explained

by the fact that while the present study investigated the prevalence of

women ever experiencing alcohol-related IPV, the South African study

reported prevalence for the past twelve months.

Following the same trend as IPV, it is possible that the occur-rence

of current alcohol-related violence may be higher than past occurrence.

Women who have experienced alcohol-related violence may recall these

incidents more since they are more recent than if they took place a long

time ago. Another possible explanation for this is that in South

Africa, it is believed that alcohol causes aggres-sion and this has led

men to drink in order to carry out violent acts [2] thereby increasing

the rate of alcohol-related violence in South Africa compared to other

sub-Saharan African countries.

The Relationship between Alcohol and Intimate Partner Violence in SSA

In all ten countries, alcohol was consistently linked to women's

experience of intimate partner violence with the nature of the

re-lationship varying across different countries. The findings of this

study showed that in seven out of the eleven countries (Ghana, Ken-ya,

Liberia, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe), there was no

significant difference in the odds of experiencing IPV in women whose

husbands/partners never consumed alcohol and those whose

husbands/partners never got drunk. This is consistent with the findings

in several literatures [2,3,16]. This can be explained by the fact that

for alcohol to significantly increase the odds of perpetrating intimate

partner violence, alcohol consumption has to surpass a particular amount

or rate of consumption.

This explanation is consistent with that put forward by propo-nents

of the threshold effect who argue that it is not alcohol con-sumption

per se that contributes to intimate partner violence but alcohol abuse.

Conversely, in Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Sao Tome and Principe, women

whose husbands consumed alcohol but never got drunk were significantly

more likely to experience any of physical, sexual or emotional intimate

partner violence than women whose husbands never consumed alcohol. This

is similar to the report of Bangdiwala et al. [20] who reported a strong

linear re-lationship for the alcohol-IPV link. These results are in

agreement with the justification put forward by the proponents of the

linear effect conceptualization who maintain that alcohol abuse

increases the odds of intimate partner violence and that these odds

increases with increase in the quantity of alcohol consumed.

In Kenya alone, the odds of alcohol increasing the odds of in-timate

partner violence only reached statistical significance in the women

whose husbands/partners often got drunk. This indicates that in Kenya,

it is the frequency of alcohol abuse and not abuse alone that

contributes to the alcohol-IPV link. Drawing from the multiple threshold

conceptualisation [21], it is possible that the likelihood of

experiencing intimate partner violence in Kenya is already very high

that alcohol consumption or less frequent alcohol abuse does not

significantly contribute to an increased odd of intimate partner

violence while more frequent alcohol abuse may increase the frequency

and severity of intimate partner violence in this sample thereby

increasing the likelihood of intimate partner violence in this group.

The findings of this study support both the linear and threshold

conceptualisation of the alcohol-IPV link. This suggests that the type

of relationship between alcohol and intimate partner violence varies

across countries in sub-Saharan Africa with most countries showing a

threshold effect. This observed difference could be as a result of

differences in drinking pattern. In the seven countries where threshold

effects were observed, large percentages (86.3 to 99.1%) of men who

drink get drunken showing drinking cultures that are supportive of

alcohol abuse.

Strength of Alcohol-Intimate Partner Violence Link in SSA

A meta-analysis of the ten countries included in this study showed an

odds ratio of 2.91 (95%CI, 2.24-3.39) for physical IPV which shows that

women whose husbands abuse alcohol are almost thrice as likely to

experience IPV than women whose husbands do not abuse alcohol. This

shows a strong association between alcohol and intimate partner violence

in sub-Saharan Africa. This is consistent with the strong association

reported in a meta-analysis by Gil-Gonzalez et al. [22]. The strong

association between alcohol and physical IPV in this study can be

explained by the culture of masculinity in sub-Saharan Africa. It is

considered masculine for men to drink and it is also seen as a thing of

pride for a man to be feared and respected by his wife. It is also

generally acceptable for men to physically reprimand their wives if they

feel that the women have erred in anyway.

On the other hand, a small but significant relationship was observed

for alcohol and sexual intimate partner violence in this study. This is

similar to the report of Tang and Lai [23] who report-ed a significant

but weak association between alcohol abuse and sexual intimate partner

violence. This weak association could be as a result of the fact that in

African society, sex is considered a private matter not to be discussed

with strangers. There is also shame as-sociated with being raped and

made to perform unwanted sexual acts and women are often blamed for it

and this may result in under reporting. Women may also consider that

being made to perform any form of sexual act is acceptable so long as it

is within a marriage or committed relationship and may not consider

this as IPV. For example, it is commonly believed in Africa that a man

cannot rape his wife. Hence forced sexual intercourse in a marriage is

not considered rape but seen as a normal part of the relationship. When

the severity of intimate partner. Based on the results from this

re-search, it can be argued that the strength of the alcohol-IPV link in

sub-Saharan Africa depends on the type of IPV measured.

Conclusion

The purpose of this research work is to identify the relationship,

strength of relationship between alcohol and intimate partner violence

in sub-Saharan Africa. Results of this study show that alcohol is

consistently associated with intimate partner violence in all ten

countries included in this study with the strength of this relationship

depending on the form of intimate partner violence. While a linear

relationship was found between alcohol and intimate partner violence in

Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Sao Tome and Principe, a threshold effect was

observed in the remaining seven countries with the odds of

alcohol-related intimate partner violence increasing with increase in

alcohol consumption and alcohol abuse. The strength of the

alcohol-intimate partner violence link was also found to be dependent on

the effects of other variables in some countries with the direction of

moderation different in the countries where these moderation effects are

present.

The results also show that when the three forms of IPV were measured,

the prevalence of both IPV and alcohol-related IPV were higher than

that of existing literatures suggesting that studies of IPV estimating

only one or two forms of IPV are subject to under es-timation of the

magnitude of his huge public health problem. These findings have

potentially important implications for public health promotion, policy

and practice. The implication of the findings of this research is that

interventions for tackling alcohol-related IPV should be multifaceted

and should address behavioural, cultural and social change

Study Limitations

Despite the above strengths, the result of this study should be

interpreted bearing in mind several limitations. First, because the

information on problem drinking was provided by women, there is the

possibility of misclassification bias. Responses were not taken from men

about their drinking and IPV perpetration and this would have been

valuable in corroborating the women report. There is also a tendency for

recall bias as IPV may have taken place at a different time from

alcohol abuse. Classification of drinking as sometimes or often drunk

makes the report subjective rather than objective and may have led to

results showing a stronger relationship between alcohol and IPV in

sub-Saharan Africa. This is because studies have shown that studies

assessing alcohol abuse is more associated with IPV than those measuring

quantities [24].

Even though the results of this research are to a great extent

consistent with those reported for community samples in other studies,

it cannot be generalised to clinical samples of alcohol abusers or IPV

perpetrators because studies have shown that the magnitude of the

association between alcohol and IPV is stronger in clinical than

community samples [24]. Finally, because this study analysed data from

cross sectional studies which are ecological in nature, it is difficult

to know if problem drinking took place before IPV or vice versa. It is

possible that perpetrators of IPV are more likely to misuse alcohol or

that individual's use alcohol to cope with stressful life events hence

causality cannot be assumed.

Read More about Lupine Publishers Journal of Research & Reviews Please Click on below Link:

https://lupine-publishers-research.blogspot.com/