Lupine Publishers | Journal of Food and Nutrition

Abstract

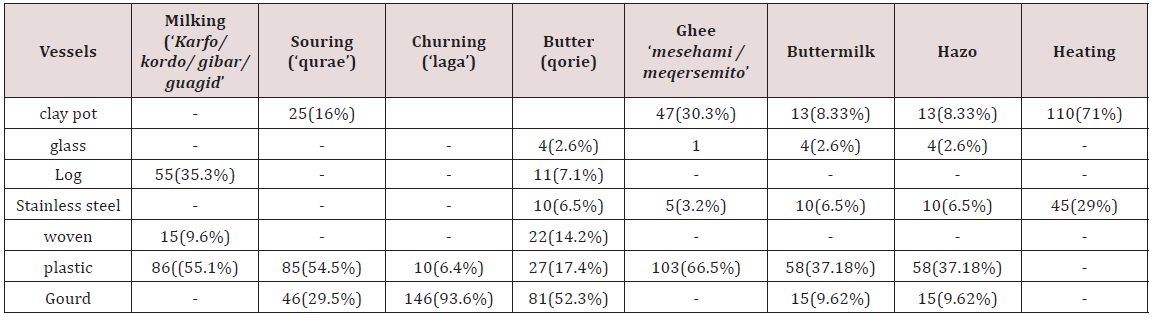

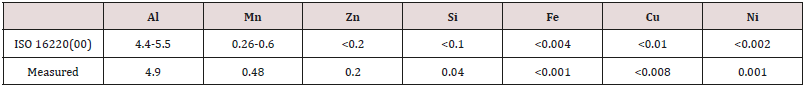

Cross-sectional study conducted with the aim of assessing milk products handling, processing and to characterize utilization practices in dairy farmers of Ofla, Endamekoni and Embalaje highlands of Southern Tigray, Ethiopia. A total of 156 households possessing a dairy farmers, of which 47 urban, 20 periurban and 89 rural were studied using Probability proportional to size approach sample determination. Using butter as hair ointment and custom of dying white close. About 42.31% respondents sell fresh milk, 1.92% buttermilk and yoghurt, 98.08% butter to consumers of which 93.26% of them were rural respondents. Local vessels were treated with different plant materials by cleaning and smoking. Milking vessels used ‘gibar’, plastic materials and ‘karfo’, milk souring utensils ‘qurae’ made of clay pot, plastic vessels or gourd; ghee storing 66.03% respondents in plastic, 30.13% used ’qurae’ and 3.21% use stainless steel vessels. There was significant (p<0.05) difference in the use of churning vessels in the study area where 93.6% of respondents use ‘Laga’ while the others use water tight plastic vessel.

Butter handling practice, is using ‘qorie’ :- Glass, stainless steel, log, ‘gibar’, plastic and gourd. The log ‘qorie’ was best butter handling. Butter milk (‘awuso’) and spiced butter milk ‘hazo’ stored in clay pot, plastic and stainless steel of the different milk products. Plants species used to improve milk products shelf life, cleaning and smoking of utensils includes: Olea europaea, Dodoneae angustifohia and Anethum graveolens; while Cucumis prophertarum, Zehneria scabra sonder and Achyranthes aspera were naturally rough to clean grooves of the clay pot and churner. The practice could be a base line study to cope up the problems in health risks, quality, taste and shelf life of milk products. Due attention for indigenous practices could be vital to improve livelihood of farmers’.

Keywords: Milk handling and Processing, Preservative plants

Introduction

In Ethiopia, the traditional milk production system, which is dominated by indigenous breeds of low genetic potential for milk production, accounts for about 98% of the country’s total annual milk production. Processing stable marketable products including butter, low moisture cheese and fermented milk provided smallholder producers with additional cash source, facilitate investment in milk production, yield by products for home consumption and enable the conservation of milk solids for future consumption [1]. According to Lemma [2], storage stability problems of dairy products exacerbated by high ambient temperatures and distances that producers travel to bring the products to market places make it necessary for smallholders to seek products with a better shelf-life/ modify the processing methods of existing once to get products of better shelf-life. Smallholders add spices in butter as preservative and to enhance its flavour for cooking [3]. Farmers rely on traditional technology to increase the storage stability of milk products either by converting the milk to its stable products like butter or by treating with traditional preservatives [4]. Identification and characterization of these traditional herbs and determination of the active ingredients and methods of utilization could be very crucial in developing appropriate technologies for milk handling and preservation in the country [2].

The contribution of milk products to the gross value of livestock production is not exactly quantified (Getachew and Gashaw, 2001). The factors driving the continued importance of informal market are traditional preferences for fresh raw milk, which is boiled before consumption, because of its natural flavour, lower price and unwillingness to pay the costs of processing and packaging. By avoiding pasteurizing and packaging costs, raw milk markets offer both higher prices to producers and lower prices to consumers (Thorpe et al. 2000; SNV 2008). Packaging costs alone may add up to 25% of cost of processed milk depending on packaging type used. Polythene sachets are cheaper alternatives (SNV, 2008). ‘When there is no bridge, there is always other means!’ [5], that the highland dairy farmers coping mechanisms to exploit their milk products rely up on local plant endowments even though it is not quantified.

Unlike the ‘Green Revolution’ in crop production, which was primarily supply- driven, the ‘White Revolution’ in developing economies would be demand-driven [6]. In Ethiopia, particularly, the highlands of Southern Tigray, where previous research is very meagre, the dairy products, mainly milk, butter and cheese are peculiarly exploited products than any other areas since long period of time but the doubt is their extent of production in comparison to their demand, nutritional needs and economic values, that is why the objective of this paper has targeted on the main dairy products exploitation degree in relation to the livestock resource potential. Thus research objectives are :

To identify milk production practices and constraints in the study area, and

To assess milk products handling, processing and utilization practices and methods.

Materials and Methods

Description of the Study Area

The research was conducted in Embalaje, Endamekoni and Ofla Wereda of Southern Tigray, from December, 2011-February 2012. The districts are located from 90-180 km south of Mekelle city & 600-690Km north of Addis Ababa. The study area is categorized as populated highland of the country where land/household is 0.8ha. Maichew is located at 12° 47’N latitude 39° 32’E longitude & altitude of 2450 m.a.s.l, and has 600-800mm rainfall, 12-24oC temperature, and 80% relative humidity. Korem is sited on 120 29’ N latitude, 39o 32’E longitude and Adishehu is located on 120 56’N latitude and 390 29’E longitude [7].

Study Population and Sampling Procedures

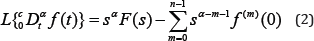

Data was analyzed using SPSS & excel. Household respondent used as sampling unit in the study and sample size determination was applied according to the formula recommended by

Arsham [8] for survey studies: SE = (Confidence Interval)/ (Confidence level) = 0.10/2.58 = 0.04, n= 0.25/SE2 = 0.25 / (0.04)2= 156

Where, confidence interval=10% and confidence level=99%

Where: N- is number of sample size

SE=Standard error, that SE is at a maximum when p=q =0.5,

With the assumption of 4% standard error and 99% confidence level.

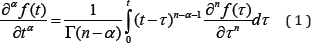

Figure 1: Act of milk processing a) Cucumis prophertarum milk vessel scrubbing b) and c), churner smoking using Anethum graveolens d) Act of churning ; e) A grass inserted in to churner (‘Laga’) to determine ripeness of butter f) g) and h) Butter separation and i) Butter bathing in water.

Result

Milk Processing and Utilization Practices in Highlands of Southern Tigray

Churning: The dairy farmers practiced traditional milk processing to increase shelf life and diversify the products as soured milk, buttermilk, hazo, whey, butter and ghee that have significant nutritional, socio-cultural and economical values. ‘Laga’ hamaham (Cucurbita pepo) gourd was used in 93.6% of respondents of the study areas to churn, that could hold about 10-15 litres of accumulated milk. Procedurally Laga is washed and smoked, they heated the yoghurt to speed up butter fat globule formation, pour to the churner for churning and then let air from the churner in 15 minutes interval rest then finally, they insert a grass to check up its ripeness and pour in widen vessel to squeeze out the fat globules formed from butter milk (Figure 1). Fermented milk- yogurt “Ergo”, a traditionally fermented milk product, semi solid with a cool pleasant, aroma and flavour, used as unique medicine “tsimbahlela” during emergence and revive a person from shock and dehydration that’s why a cow is respected and considered as common resource of the surrounding in the study areas.

Buttermilk (‘awuso or huqan’) is a by-product of butter making from fermented milk. Buttermilk is either directly consumed within the family or heated to get whey/‘mencheba/aguat’ for children and calf consumption and cottage cheese known as ‘Ajibo/ayib’ for family. hazo-Fermented buttermilk with spices to extend shelf life and to provide special aroma and flavour for special occasions like socio-cultural festivals termed ‘hazo’. In holidays, 96% of dairy owners practice hazo gifts to their neighbours about a litre to each household. Even a widow who engaged in herding calves to earn weekly rebue milk, give hazo to neighbours with no milking cows. Ghee (‘Sihum’) or butter oil prepared from cows or goats milk was a special ingredient of holiday dish in majority of the dairy farmer respondents. Besides to its nutritional, ease of storage, ghee is more preferred asset for its nutrional content, ease of storage and longest shelf life, with minimum spoilage followed by butter 6 months, while shelf life of hazo is 2 weeks.

Fresh milk, yoghurt, buttermilk, whey, cottage cheese (‘Ajibo’), hazo (spiced fermented butter milk), butter and ghee (‘Sihum’) were among the common dairy products in the area with varying degree, that of fresh milk and yoghurt, were reserved for further processing, while hazo and ghee were consumed occasionally. Concerning to milk utilization, the rural household dairy farmers dominantly used the available milk for family food consumption. Dairy farmers were categorized based on marketable milk products that 98.08% of them sell butter, 77.56% of them sell fresh milk, 4.49% of them sell buttermilk and 1.92% of the respondents sell yoghurt .where as none of the respondents sell ghee, cheese, whey and hazo milk products. A farmer remarked as “honey is for a day while milk is for a year!” indicating the nutritional significance to invest for beloved family. Majority of the dairy owners were intimated with their neighbours for they do have social ties and they share animal products like the priceless life saving ‘tsimbahlela’- yoghurt during emergencies.

Milk Products Handling and Processing Vessels: Clay pot, gourds, some unreliable sourced iron and plastic containers are used for liquid milk while broad leaves like castor oil and grass weaved could serve as butter handling materials, which have sanitation problems because of grooved and irregular shapes. However, dairy farmers adapted and appreciate the rough nature of the gourds (qorie for butter storage, qurae for souring, Laga for churning and karfo for milking) and clay pots as souring and heating vessels for it absorb smoke (the disinfectant and preservative).

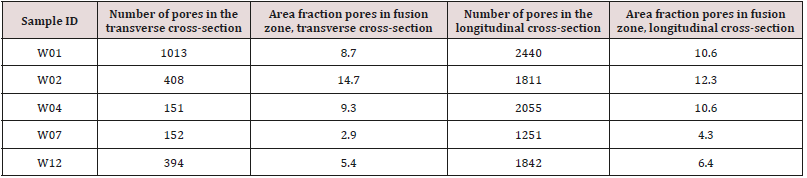

Milking vessels used in the study area were gibar (woven grass smeared by Euphorbia tirucelli sabs) in 9.62%, plastic jogs in 55.13% and log ‘karfo’ in 35.26% respondents. Souring vessel used by respondents was 16% clay pot, 54.5% plastic, and 29.5% gourd made of Cucurbita pepo (hamham). Ghee storage practice of the respondents was also 66.03% in plastic/ glass vessels, followed by 30.13% in clay pot termed as ‘qurae or tenqi’ and 3.21% in stainless steel vessels. gibar or agelgil was more used in Embalaje Wereda followed by Endamekoni and Ofla areas. There was significant (P<0.05) difference in churning vessel use in the study area that gourd ‘Laga’ user respondent were 93.6% while other water tight plastic vessel churner user respondents were 6.4%.

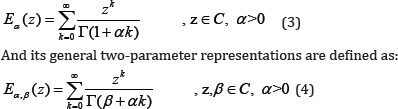

Butter handling practiced in general in ‘qorie’ type of material. Based on the respondents’ information where to store butter is stored in 2.6% glass, 6.5%)stainless steel, 7.1%log, 14.2% woven grass termed locally as ‘gibar /‘agelgil’, 17.4% plastic vessels and 52.3% gourd. Respondent remarked gourd as well insulated but difficult to in and out butter than woven grass. The log qorie was best butter handling, but not easily accessible these days because of deforestation problems that some do get from Afar region. Butter milk termed as ‘Awuso or huqan’ and spiced butter milk ‘hazo’ vessel practiced in clay pot, plastic and stainless steel. Fresh milk and butter milk boiled in stainless steel (71%) or clay pot (29%) while butter extracted in to ghee using clay pot (Table 1).

Data in bracket indicate proportion of respondents who used the milk product vessels.

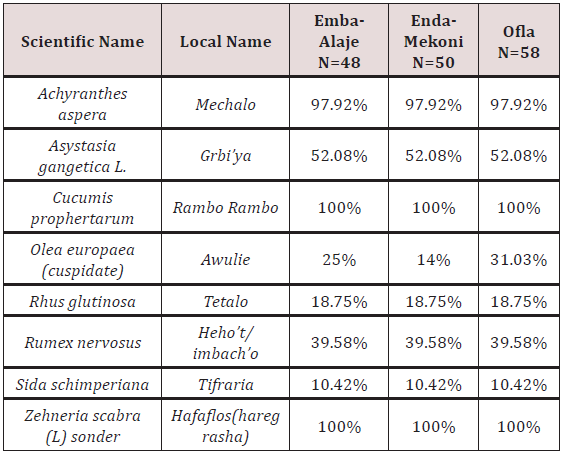

Plants used to Clean (Scrub) Vessels of Milk Products

The dominant milk vessel washing herbs used in all the study areas were Cucumis prophertarum (‘ramborambo’) that prevent defragmentation of yoghurt from rarely souring problems and multi-medicinal value of their livestock, Zehneria scabra (L. fil) sonder (‘hafafelos or hareg rasha’) and Achyranthes aspera (‘mechalo’) were all rough in nature to clean the grooves of the clay pot (‘qurae’) and churner (‘Laga’) besides to their disinfectant nature. Rumex nervosus, Rhus glutinosa, and Asystasia gangetica were alternatively used. Sida schimperiana was blamed to wash clay pot which used for local brewery vessels alone, but very rare respondent argued as alternatively scrubbing vessels of milk products (Table 2).

N= Number of respondent used to practice.

Many respondent prefer Cucumis prophertarum to speed up fermentation and uniform fat texture of yoghurt. Zehneria scabra is a multifunctional herb used by many people, women in particular exploited for its medicinal value, could act as disinfectant. Olea europaea was a multifunctional tree, its leaf alternatively served to clean milk vessels that rural dairy farmers in particular 31.03% of respondents from Ofla followed by 25% respondents of Emba- Alaje, dominantly used it for scrubbing while the urban dairy respondents do have access of the dry wood to smoke. The usage of such plants along with the locally available vessels led the tradition of milk utilization practices, preferable more than technological innovation, for the immense natural aroma and flavour.

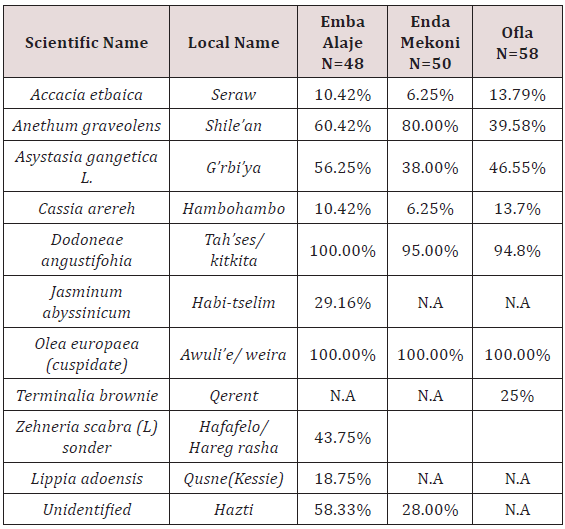

Plants used for Smoking the Milk Vessels: Three dominant plants exploited for smoking milk vessels were Olea europeana, Dodoneae angustifohia and Anethum graveolens in decreasing order in the study areas, just for fumigation, extend shelf-life, aroma and flavour due to scent scenario of the plants. Household preference and agro-ecology difference could contribute to the variety plant usage that Emba-Alaje Wereda respondents alternatively used smoke of Jasminum abyssinicum (‘habi-tselim’), ‘hazti’ and ‘qusne’ that were distinctive to the peak highlands of Tsibet and Alaje mountain chains. Accacia etbica, Asystasia gangetica and Cassia arereh were also another resource to all study sites. Optionally Terminalia brownie (‘qerenet’) was typical to Ofla Wereda (Table 3).

NA.= Not Available

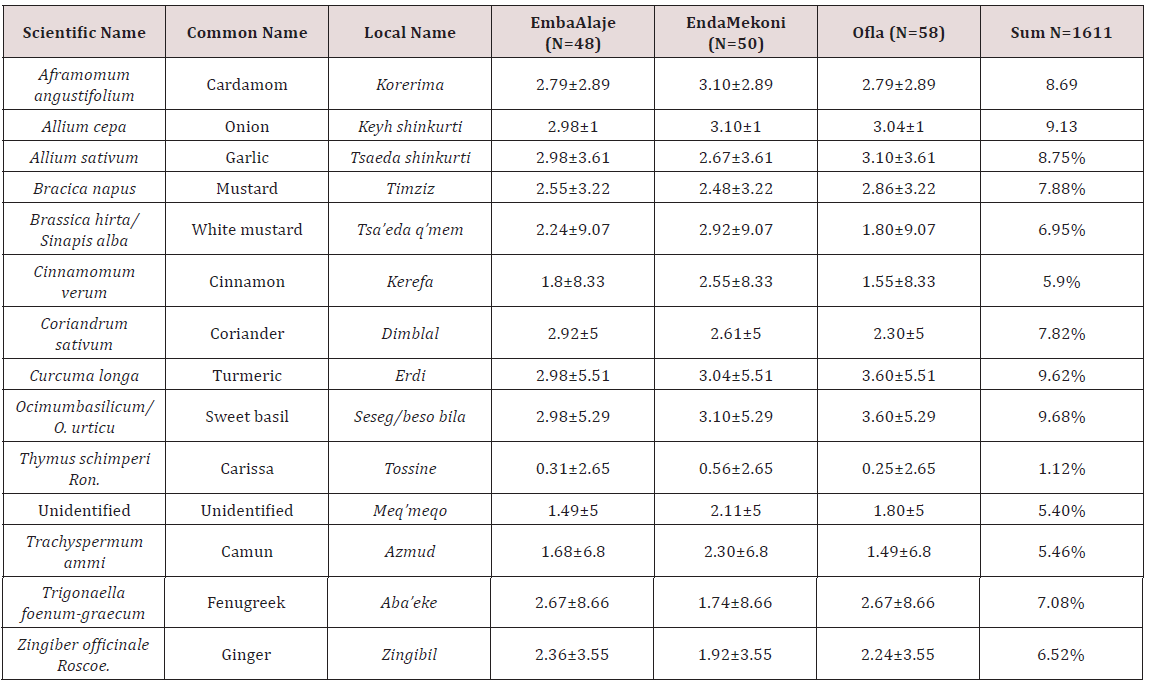

Plant Species used in Ghee (‘Sihum’) Making: The amount of spice ingredients used in ghee preparation varies from household to household according to experience and access. Curcuma longa (‘erdi’) served as colouring agent of ghee that majority of respondents deemed yellowish ghee colour is attractive. The ghee spices add value in terms of shelf-life, scene (aroma & flavour) and nutritional combinations of special ingredients (Table 4).

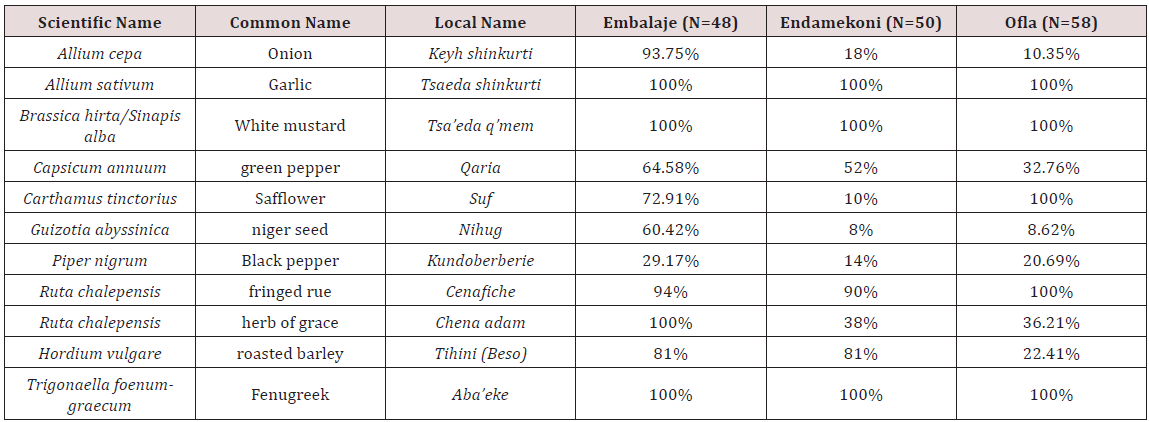

Spices used in hazo Preparation: Out of 1088 citation for hazo preparation spices (Table 5) recorded according to priority were: Allium sativum (14.34%), Brassica hirta/Sinapis alba (14.34%), Trigonaella foenum-graecum (14.34%), Ruta chalepensis (13.6%), Carthamus tinctorius (9.01%), Ruta chalepensis (8.9%), Hordium vulgar (7.26%), Capsicum annuum (6.99%), Allium cepa (5.52%), Guizotia abyssinica (3.49%) and Piper nigrum (33). Besides to ingredient value, the spices added in hazo enhance shelflife through fermentation of buttermilk.

Butter Packaging Practices: Based on respondents’ preference of butter packaging leaves 62.18% of the respondents used Racinus communis, 1.92% used Cassia arereh and 1.28% used Cordia africana plant leaf used as butter packaging material in the study areas. 34.62% of the respondents from urban and periurban prefer plastic package than leaves. According to some respondents the leaves were used culturally and practically for no effect over all butter property, being smooth and larger size uniformly, no butter wastage remains there, moreover, the leaf provide protection from heat. Concerning to utensil ‘qorie-log /gourd or gibar was mentioned according to their preferences based on heat protection for the butter. However, butter traders do prefer to hold on larger sized plastic pail or other stainless vessels. The effect of the packaging leaf on the quality and characteristics of butter deserves further investigation.

Discussion

The mean value of family size in the study areas 4.6±1.84 persons was comparable to CSA [7] report which was 4.5 for Endamekoni, 4.29 for Ofla and 4.36 persons for Embalaje. With the poor access of technological preservatives and processing utensils, milk products could have been perished, but many thanks to the indigenous knowledge practices of plant uses to speed up fermentation, to prevent milk spoilage and to enhance butter colour, milk products aroma and flavour supported with reports of Lemma [2]; Asaminew [3] and Hailemariam & Lemma [9].

Based on the keen observation, dauntless courage and optimism of the dairy farmers’ information, some plant such as Asystasia gangetica L. ‘giribia’ used in smoking milk utensils, just to give reddish colour of the butter, was blamed for milk bitterness that should be further investigated. Three dominant plants exploited for smoking milk vessels were Olea europaea, Dodoneae angustifohia and Anethum graveolens and the dominant milk vessel washing herbs used were Cucumis prophertarum that prevent fat defragmentation & souring problems and multi-medicinal value of their livestock, Zehneria scabra sonder and Achyranthes aspera were all rough in nature to clean the grooves of the clay pot and churner besides to their disinfectant nature. This agrees with the finding of Amare (1976); Ashenafi [4]; Lemma [2]; Asaminew [3]; Hailemariam & Lemma [9] that smoking reduced undesirable microbial contamination and enhances the rate of fermentation.

The study is similar in souring as stated by Ashenafi [4] that dairy processing, in Ethiopia, from naturally fermented milk, with no defined starter cultures used to initiate it. In many parts of Ethiopia, milk vessels are usually smoked using wood splinters of Olea europaea to impart desirable aroma to the milk. Smoking of milk containers is also reported to lower the microbial load of milk. Plant leaves of Racinus communis (‘gulei’) followed by Cassia arereh (‘hambohambo’) and Cordia africana (‘awuhi’) used as butter packaging material dominantly. The present study shows that Racinus communis and Cassia arereh are typical plant leaves to the study areas unlike Cordia africana that was reported in Hailemariam & Lemma [9] in East Shoa. Spices used in ‘hazo’ preparation were Allium cepa, Allium sativum, Brassica hirta/Sinapis alba, Capsicum annuum, Carthamus tinctorius, Guizotia abyssinica, Piper nigrum, Ruta chalepensis, Sativium vulgar, and Trigonaella foenum-graecum. Asaminew [3] reported about ‘metata ayib’ in Bahir-Dar that is relevant utilization practice of milk products.

Storage materials preference was based on their ability to retain flavour of fumigants and herbs used. Gourd ‘Laga’ or rarely water tight plastics were churning vessels of the study area unlike to clay pot churner reported by Alganesh [10] for East Welega and Asaminew [3] in Bahirdar. Alganesh reported that gourds were used commonly for storage and even for milking purpose. This indicates that the utensils used for milking, processing and storage were different from place to place and even from household to household. Efficient churning materials could contribute to lesser time and energy requirement besides to the economic return of higher butter yield for small holder dairy who do suffer from discouraging market during fasting of lent. Inefficient churner use contributed to less butter exploitation as stated by researchers (O Conner [11]; Alganesh [10]; Zelalem [5]).

Fresh milk, yoghurt, buttermilk, whey (mencheba), cottage cheese (Ajibo), hazo, butter and ghee (‘Sihum’) were among the common dairy products in the area with varying degree, that of fresh milk and yoghurt, were reserved for further processing, while hazo and ghee were consumed occasionally. The result is consistent with many of the research findings Lemma [2]; Asaminew [3] & Zelalem [5]. The limited consumption of butter may be due to the higher price associated with it and the need for cash income to buy some necessities. Butter can fetch them a good price compared to other milk products. Butter was consumed only during holidays and special occasions in rural low-income households because it fetches routine cash income Asaminew [3].

Different spices were used in ghee making. The finding was consistent with the reports of Alganesh [10] in East Wellega, Lemma [2] and Hailemariam and Lemma (2010) in East Shoa. Ghee was not marketed in the areas surveyed due to consumers’ preference to make their own ghee depending on their test and preference for different spices that the finding has close affinities with Hailemariam & Lemma [9]. Compatibly with Asaminew [3], consumers /traders consider the colour, flavour, texture and cleanness of the products during transaction, that butter quality requirements fetch a good price. During the dry seasons butter price increase, this is related to abridged milk yield of cows due to the insufficient feed supply. Higher price was also paid for yellow coloured and hard textured butter that deemed to be higher in dry matter or solid non fat for extraction consistent with reports Asaminew [3].

In the districts those smallholders who do not sell fresh milk had different reasons. These were small daily production of fresh milk, cultural barrier, lack of demand to buy fresh whole milk and preference to process the milk into other products. Similar reports were made by Alganesh [10] and Lemma [2]. Besides, it is difficult to find a market. Typical to the research observation on milk marketing problems, the Ethiopian highland smallholder produces a small surplus of milk for sale. The informal system where the smallholder sells surplus supplies to neighbours or in the local market, either as liquid milk or butter but contradict in cottage-type cheese called ayib. Sintayehu [12] selling that was unusual including buttermilk, ‘hazo’, whey, cottage cheese and ghee. In the vicinity of larger towns the milk producer has a ready outlet for his liquid milk. However, in rural areas outlets for liquid milk are limited due to the fact that most smallholders have their own milk supplies and the nearest market is beyond the limit of product durability like to many of the studies done (Getachew and Gashaw (2001); Sintayehu [12]; SNV (2008); Tesfaye et al. (2010)) besides to cultural traditions and lower talents entrepreneurship of the farmers.

Many research findings similarly stated that there were several constraints to the dairy in particular to milk marketing development, e.g. lack of infrastructure and finance, seasonality of supplies and lack of market structure and facilities [3]. Because of the lack of cooling facilities or even suitable utensils for milking and storing, milk deteriorates rapidly [11]. Milk is often sold for less than its full value due to lack of access to markets, poor road infrastructure, lack of co-operatives, inability to transport long distances due to spoilage concerns, and unscrupulous traders who add water or other fillers the study was consistent with PPLPI (2009) and cultural taboos and discouraging market [3]. Contrary to perceived public health concerns, the marketing of raw milk does not pose public health risks as most consumers boil milk that consistent was Kurwijila [13] and exploit local herbal resources to smoke and clean the milk products vessels that served as disinfectant, preservative, tasteful with natural aroma and flavour Asaminew [3] ; Desalegn [14] & Zelalem [5] before drinking it.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Livestock production plays an important role in the socioeconomic and cultural life of the people inhabiting in the mountainous chains of the area. The cows fulfil an indispensable role for the dairy farmers serving as sources drought ox, milk food, income from sale of butter, the only determinant women hair lotion, source of dunk cake fuel and served as prestige and confidence to avert risks. The respondent remarked “Wedi Lahimika -for own bull and no one could cheer you what a cow could do indeed” to mean reliable resource and do have special dignity for the cow.

Milk produced every day was collected in the collection clay pot, plastic vessels or ‘Laga’ smoked with woods called Olea europeana, Dodoneae angustifohia, Anethum graveolens Acacia etbaica, Terminalia brownie, and in some cases Cassia arereh and the dominant milk vessel washing herbs used were Cucumis prophertarum that prevent yoghurt from defragmentation during rarely souring problems and multi-medicinal value of their livestock, Zehneria scabra (L. fil) sonder and Achyranthes aspera were all rough in nature to clean the grooves of the clay pot and churner besides to their disinfectant nature. As reported by respondents, the purpose of smoking was to minimize products spoilage during storage and to give good aroma and flavor. Keeping milk or milk product for longer period without spoilage and flavor was indicated as main reasons for using plants in washing (scrubbing) dairy utensils [15].

Materials Commonly used for Milk Collection Storage and Processing included Clay Pot, Glass Container, Wooden Container, Plastic Container, Woven Materials, Plastic Container and Gourd

1. The emerging markets of buttermilk and yoghurt in farm gates should be expanded to other means of marketing systems via integrated awareness creation

2. The effect of these materials on the shelf- life of stored or preserved butter deserves further investigation. The impact of local herbs used as preservatives should be further studied [15].

3. Facilities for cleaning and overnight storage, milk churns and dairy utensils are rudimentary, requiring intervention.

Read More Lupine Publishers Journal of Food and Nutrition Please Click on Below Link:

https://lupine-publishers-food-and-nutrition.blogspot.com/