Lupine Publishers | Current Investigations in Agriculture and Current Research

Abstract

Food safety has always been and continues to be a major concern for all countries of the world. This concern is all the more perennial in the developing countries like Benin with a low economic level and still rudimentary and extensive agriculture. To reduce a little bit of food insufficiency, is developed urban and peri-urban agriculture based mainly on market gardening. This study focused particularly on the production of onion in southern Benin. It aims to analyze its performance, to understand the importance of this activity but also to see what are the obstacles faced by these producers. Three municipalities were investigated: Grand-Popo, Cotonou and Sèmè-Kpodji. A total of 60 farmers were surveyed at 20 per municipality. Quantitative and qualitative tools were combined for the analysis of data collected through individual and group interviews. A joint analysis approach was used to achieve specific objectives. It consists to combine speech analysis, participant observation with statistical tools such as the frequency distribution, the regression model and calculation of performance indicators. It follows from all of these analyzes that onion production is profitable from a financial point of view. This performance is enhanced by factors such as age, experience and membership of a producer group. Similarly, the farmers claimed for majority that onion occupies a special place in their market garden production. This production improves their socio-economic and food situations. However, the constraints that undermine the more onion production and thus constitute important producer concerns are financial, institutional, organizational, property constraints and those directly related to production. Farmers therefore, expect a little more effort from agricultural policies to improve the development of this sector.

Keywords: Onion, Performance, Importance, Barriers, Southern Benin

Introduction

The agricultural sector provides essentially food security and livelihood in Benin, with 70% of the population earning their income from agriculture [1]. This sector is even more important for developing countries like Benin, where it is one of the pillars of the economy [2]. Nowadays, it is increasingly recognized that in the developing world, nearly three billion people live on less than US $2 per day [3]. Majority of this population are smallholder farmers producing staple food crops with little prospects of generating higher incomes. Hence, diversification into high-value horticulture is essential for increasing farm incomes, alleviating poverty and improving livelihoods [4,5]. Globally, food production is still a challenge [6,7], especially with the projected rise in world population to over 9 billion by 2050 and increased urbanization in cities [8]. There is therefore still some justification for increasing agricultural production in the coming years [9,10]. Urban vegetable production is an intensive agricultural strategy through which urban dwellers secure income and improve their livelihoods [11].Urban and periurban agriculture (UPA) has been defined differently by Mougeot [12,13], Moustier [14], and Van Veenhuizen [15], but they all lay stress on agriculture’s relationship with the city as a resource and destination for outputs [16].

Onion (Allium cepa L.) is one of the most important commercial spice crops of the world belongs to Amaryllidaceae family [17]. Moreover, essential oil and sulfur compounds have been found in onion which is responsible for unique odour, flavour, and taste [18]. Based on the interested situation in health food development, the properties of onion and its extract as a functional agent have been demonstrated in many previously [19]. Onion (Allium cepa L.) has been valued as food and medicinal plant since ancient times [20]. It is widely cultivated secondly to tomato, and is a vegetable bulb crop known to most cultures and consumed worldwide [21]. The major onion producing countries of the world are China, India, USA, Turkey, Japan, Spain, Brazil, Poland and Egypt [22]. In Benin West African country, this culture has become very important especially in urban areas where the market gardeners devote more land to the production of onion. It is in order to make an inventory and understand onion production in southern Benin that this study was conducted. Specifically, the study aims to analyze firstly the profitability of onion production, secondly to appreciate the importance of onion production in southern Benin and ending by identifying the difficulties facing the farmers.

Materials and Methods

Study zone

The municipalities of Grand-Popo, Sèmè-Kpodji and Cotonou are located in south of Benin and cover respectively 289km², 250km² to 79km². The town of Grand Popo is located in the southwestern department of Mono. It is limited to the north by the Athiémé, Comé and Houéyogbé communes, south by the Atlantic sea, to the southwest by the communes of Ouidah and Kpomassè and west by the Republic of Togo. Located between the parallel 6° 22 ‘and 6° 28’ north latitude and the meridian 2° 28 ‘and 2° 43’ east longitude, the commune of Sèmè-Kpodji is in the Department of Ouémé, the Southeast of the Republic of Benin on the Atlantic coast. It is limited to the north by the city of Porto Novo and Aguégué, south by the Atlantic sea, to the east by the Federal Republic of Nigeria and to the west by the city of Cotonou. The town of Cotonou in turn is located on the barrier beach that stretches between Nokoué Lake and the Atlantic sea, consistitued of alluvial sands of about five meters maximum height. It represents the only municipality in the Littoral department is bounded to the north by the municipality of Sô-Ava and Nokoué Lake, south by the Atlantic sea, to the east by the town of Seme-Kpodji and West by that of Abomey-Calavi. These towns are from a set that has a sub-equatorial climate except Sèmè-Kpodji bathed in a Guinean Sudanese climate. We find in these areas, the sandy type of soil, leached and hydromorphic. The municipalities of Grand-Popo, Sèmè-Kpodji and Cotonou have various socio-cultural group included the mina, the Goun, the Xwla and Toffins.

Methodology

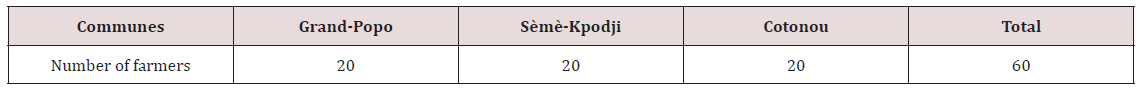

To conduct this research, three (03) municipalities were selected in southern Benin. These towns were chosen partly because of their significant contribution to the onion production of the department to which they belong, and secondly because of the large number of onion producers they contain. We have Grandpopo, Sèmè-Kpodji and Cotonou. Therefore, (60) producers made object of investigation at the rate of twenty (20) producers per commune. This sample consists only of onion producers. Note that the sample was achieved in a simple random in order to give all producers the same probability of being selected. Table 1 show the composition of the sample per commune: The collected data is related not only to the characteristics of the producers, but also to expenditure and revenue of producers. The information has been collected on the basis of a questionnaire and a pre-prepared interview guide.

Source: Results of investigation, 2018.

Data analysis

In this study, the performance of onion production in southern Benin was assessed using several indicators of financial performance. To this end, it is inspired by the work of Dédéwanou [23]. Several profitability indicators were therefore calculated, namely: Gross Product Value (PBV), Added Value (VA), the Gross Operating Income (RBE) and Net Operating Income (RNE). From Adégbola [24] and Bockel [25] studies, these indicators can be calculated as follows:

a) Product Gross Value (PBV): Denoting by Q the quantity of onion obtained and PU the selling price of the kilogram, the Gross Product Value (PBV) is given by: PBV = Q*PU.

b) The PBV is for this purpose the revenue made by the producer.

c) Added Value (VA): It corresponds to the difference between the Raw Product Noise Value and the value of intermediate inputs (CI). Intermediate consumption represents expenses related to the acquisition of insecticides, herbicides, and baskets. Its formula is given by: VA=PBV-CI.

d) The added value is obtained by deducting from the PBV, all expenses directly related to the production. Note that the added value is the wealth that the producer creates. This wealth contributes to the Gross Domestic Product of the country.

e) Gross Operating Income (RBE): It is given by the formula: RBE=VA-(Labor compensation + financial expenses + taxes). To estimate the RBE, it was considered only the hired labor.

f) Net Operating Income (RNE) This indicator represents the balance of RBE less the value of depreciation. Its formula is given by: RNE=RBE-Amortization.

g) The RNE expresses the gain (or loss) Economic agent once acquitted all current operating expenses. RNE, expresses the economic gain (or loss) given the investments made previously. Therefore RNE is obtained by deducting from the PBV all expenses related to production.

h) This study is also proposed to analyze the determinants of the profitability of onion production. For this purpose this study was based on the work of Tovignan [26] and Allagbe [27]. A multiple linear regression model has been developed on the basis of sixty (60) onion producers. Thus, the multiple linear regression formula can be written as follow:

y =α0 +α1xi+ εi

Where: y is the dependent variable, xi the explanatory variables, α is a constant called “intercept” and Ɛi the error term of the model.

The evaluation of the importance of onion production consists to determine changes in socio-economic and food orders induced by this production in the three investigated municipalities. To do this, in a collection of producer’s speeches about perceived improvements since they produce onion was done. The analysis fundamentally was based on the discourse of these producers and through participant observation. More simply, the analysis consists to explain the effects induced by the production of onion in a social context through producer’s speeches and participant observation. These explanations were supported by the comments of some significant producers. The frequency distribution and the farmer’s speeches allowed identifying the barriers of onion production in the study areas.

Presentation of the variables included in the model

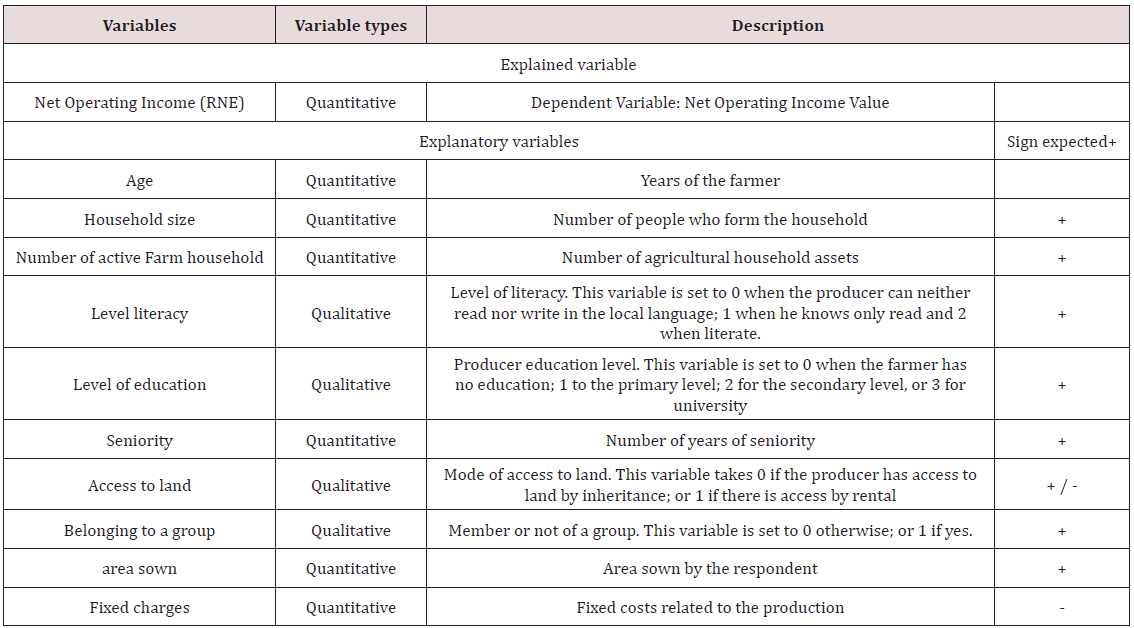

Two types of variables are included in the regression model turned. We have on the one hand, the dependent variable and the other explanatory variables. The dependent variable is the Net Operating Income of producers. It was therefore question of identified and analyzed the factors influencing the income of onion producers. So many variables called ‘’ explanatory ‘’ were introduced in the regression model. The explanatory variables included in the model are: age of the producer (Age), household size (Mena), the number of agricultural household assets (ActifM), the level of literacy (Alpha), educational level (Inst), seniority (Anc), membership of a group (APPG), the cultivated area (Sup), the mode of land access (ACCT) and fixed costs (CF).

There are a lot of reasons for the incorporation of these variables in the regression model.

a) Age: Age is a variable expressed in years. Several studies identify age as a parameter determining the profitability of agricultural production. Indeed, the more the producer is aged, the more he gains experience enabling him to improve the financial performance of its operations. This variable has been introduced into the model to see if it has an influence on the net income of onion producers in South Benin. The age would have a positive effect on the financial performance of onion production.

b) Mena: This variable refers to the number of persons who form the household of the producer. Household size is a potential source of labor and allows producers to increase production. It therefore positively influences the net income of the onion producer.

c) ActfM: This variable represents the number of agricultural workers of producer household. The number of assets would have a positive effect on the profitability of production because the market garden production, especially onions requires a lot of labor.

d) Alpha and Inst: Education can acquire a base regarding the management of a exploitation. So, educated onion producers will have a higher income than their uneducated counterparts. The effect of literacy and education on the net income would be positive.

e) Old: This is the number of the producer seniority year. Over the producer has a number of high year of seniority, the more he has strengths and knowledge that will enable him to improve his onion production. It therefore positively influences the net income of the onion producer.

f) APPG: This variable represents the membership or not of the producer to a group. It is a binary variable taking the values 1 if the producer is a member of an onion producer group or 0 if not. This variable could have a positive effect on financial performance of the production, in the sense that the producer’s group members have the support of extension services as well as that of some development programs and projects in order to improve their performance.

h) ACCT: This variable represents the farmer’s access mode to the ground. This variable is set to 0 if the producer has access to land by inheritance; 1 if access rental. The fact that the onion producer owns the piece of land to his work, it could have an influence on his income because the latter will invest the necessary capital. A positive or negative sign of the coefficient for this variable would be expected.

i) CF: Fixed costs represent costs of production. Over were these expenses less producers take advantage of his farm. These variables will therefore have a negative effect on net income of onion producers.

Source: Results of literature searches, 2018.

Table 2 shows a summary of all the variables included in the model with their expected signs. Note that two software’s were used in this section. SPSS has achieved descriptive statistics and STATA software was used to perform econometric regression.

Results and Discussion

A zoom on onion production and consumption

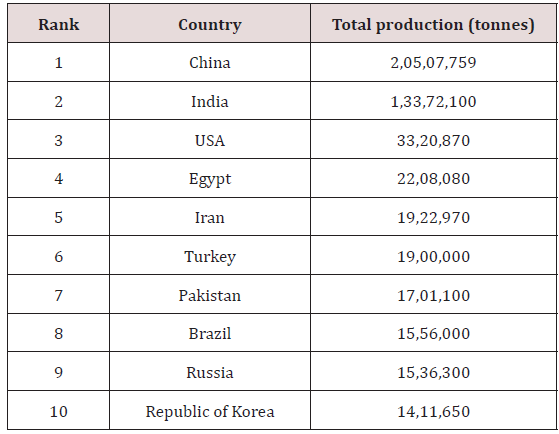

The following Table 3 shows the countries that produce most of onion in the world. China and India are the primary onion growing countries, followed by the USA, Egypt, Iran, Turkey, Pakistan, Brazil, the Russian Federation, and the Republic of Korea [21]. Onion productivity is highest in the Republic of Korea (66.16t/ ha), followed by the USA (56.26t/ha), Spain (53.31t/ha), and the Netherlands (51.64t/ha). With world production of 74,250,809 tonnes from an area of 4,364,000 hectare, the average productivity across the world is 19.79t/ha. The international trade in onion exports is 6.77 million tonnes. The Netherlands is the highest onion exporter (1.33 million tonnes) followed by India, China, Egypt, Mexico, USA, Spain, and Argentina. Bangladesh, Malaysia, the Russian Federation, the UK, Japan, and Saudi Arabia are the major onion importing countries in the world [21]. According to Bethesda [28], West Africa represents less than 2% of the world output of onion. However, it represents 10±25% of the vegetables consumption in West Africa: its culture is ancient in the region and extends through several agro-ecological zones, ranging from arid Sahelian countries to humid coastal countries [29]. In Benin particularly, the production of the onion is relatively young (40-50 years) [30].

Source: FAO, 201221.

If there is no recent and clear statistics of the volume of domestic onion production, it should be noted that the production has been in galloping development of around 70,000 tonnes against 15,000 just 20 years ago. According to Baco [31] and Affomasse [32], the average area of onion production is 1 ha in Benin representing 57% of total area under vegetable crops. Onion is the market garden predominant crop in Benin since it is grown by more than 80% of vegetable growers. Similarly, the onion is a product consumed by all the urban and rural beninese. Urban consumption is estimated at 3.3kg of onions per year per person. This demand represents a commercial demand for 7000 tonnes per year. The consumption of rural populations against is estimated at 1.1 kg of onions per year per person, a rural consumption of about 14 000 tonnes. Although the production of onion is growing, the country is unable to meet domestic demand of around 45,000 tonnes [33] throughout the year, which explains the need to import the remaining, mainly by Niger, Gaya-Malanville border [34].

Source of supply and sector’s actors

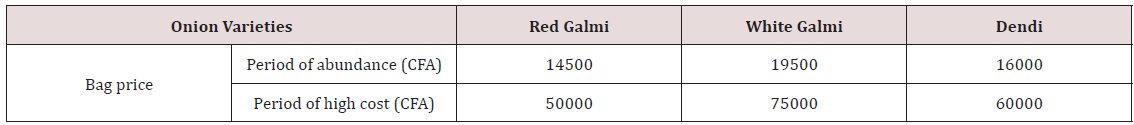

Niger, Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Benin are the biggest onion supply sources to West African consumers. Niger is the largest producer and exporter of onion in West Africa and its commercial network allows to supply the major coastal markets of the sub region. In Benin, for against the import of this speculation is more important because domestic production cannot meet the needs of people. However, nationally the most productive zones are Malanville, Karimama and Grand-Popo followed by large cities (Cotonou, Sèmè-Kpodji, Ouidah, Dassa and Glazoué) that also produce a considerable quantity of onion as urban or suburban vegetable. The production of onion, like most agricultural crops in Benin knows two periods: a period of abundance (January to May) characterized by high availability of onions on the market. Currently, importers of other countries (Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Nigeria) are sourcing local onion to neighboring countries. The second period, that of solder (August to December) is characterized by the scarcity of onions and increasing the product price on the market. In Benin, onion varieties are encountered onion Galmi (or white Galmi onion), purple Galmi (or onion Agades) and Dendi onion of Malanville (red onion or local onion). Of these varieties, the white Galmi remains the favorite onion for Beninese consumers. Besides his characteristics that one knows (bigger than the red onion, relatively smooth, easier to maintain, less spicy (less acidic)), it is its organoleptic qualities that are most appreciated (the pleasant flavor that it gives to the sauce and the fact that it does not blacken). Regarding the sale price of onions, it knows a big fluctuation depending on the period as specified above. Thus, the bag of 100kg of acceptable quality onion (red onion Galmi) and the most appreciated (white Galmi onion) respectively cost 14,500 CFA and 19,500 CFA in times of plenty against respectively 50,000 CFA and 75.000 CFA in lean period. Table 4 shows the selling price of 100 kg bag of different onion varieties in the study area.

Source: Results of investigation, 2018.

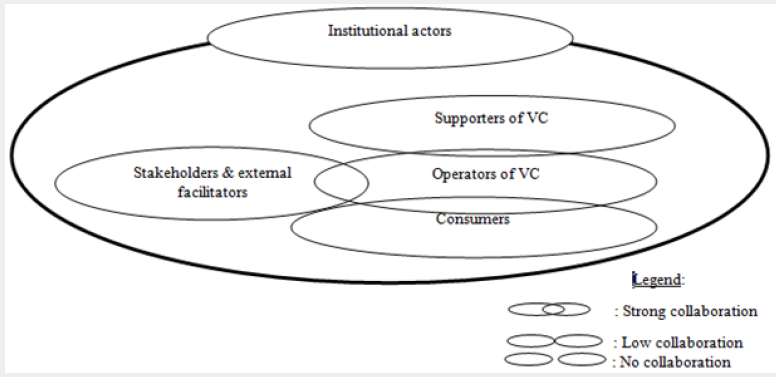

The actors in the Value Chain (VC): a multitude of stakeholders

The onion sector is composed of a large number of actors can be subdivided into four groups. It is the operators of the value chain; supporters of the chain; institutional actors; stakeholders and external facilitators

a) The operators of the value chain are most concerned. They are upstream of the value chain and are for the most part the first owners of the product. They represent producers, sellers or resellers, customers or buyers, processors, intermediaries, wholesalers and retailers.

b) The supporters of the chain are those that are not directly related to the process of production or marketing. They are actors who sell their services to producers, processors and traders. This is usually suppliers of inputs (seeds, fertilizers, pesticides), moneylenders or credit providers, pumps sellers and gasoline retailers, MFIs, intermediaries, carriers, of agricultural laborers, carters to transport the onion over a short distance etc.

c) Institutional actors are the actor’s group that provides institutional support in the context of a continuous improvement and regulation of the sector activities. These include state structures (MAEP, CECPA, SCDA, customary chiefs, customs, police, gendarmerie, research and extension services etc.). The finding done is that these groups of actors do not really invest in the development of the sector.

d) Stakeholders and external facilitators are actors who aim to improve the socio-economic life of rural populations. They provide financial and technical support primarily to producers. These are NGOs, development projects and programs, and specific fund donors.

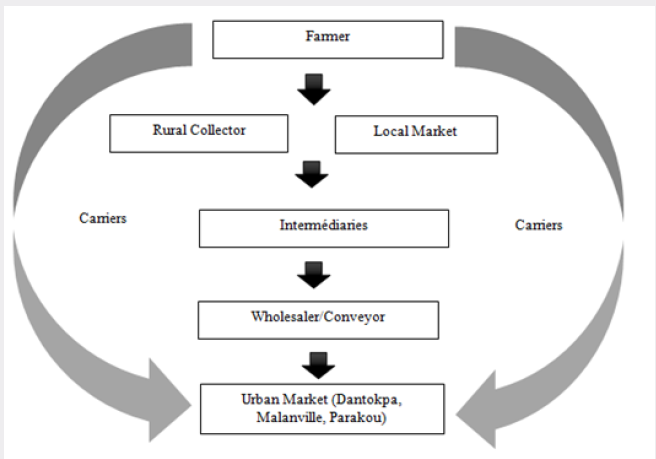

Downstream of the chain, there is a last group of actors which is relatively large: The consumers. Onion Consumers can be at any level of the chain. He may be the producer and in this case he practices subsistence farming or firm that process onion for example. It is important to note that in this sector, the actors play complementary roles. The value chain would not be good if each group of actors not playing its role effectively. The following Figure 1 shows schematically the various actors in the onion value chain in Southern Benin: In fact, some of the onions harvested by farmers are sold to rural collectors or directly to local markets. Intermediaries and wholesalers, for their part, buy onion for the most part from rural collectors or local markets. The purchased stock is then transported to urban markets (for example the Dantokpa,Malanville and Parakou markets). However, it should be noted that some producers sell their crops directly in these urban markets. The following circuit (Figure 2) shows the onion commercialization process described by respondent’s producers. All actors in the chain are present and the complementary relationship they have in the onion value chain.

Figure 1: Groups of actors in the Onion value chain in Benin.

Source: Results of investigation, 2018.

Potential and motivations of onion producers

The onion production in both North and South Benin is favored by some natural assets available in the country. It is:

a) Agro-ecological potential of Benin (soils, climate, topography, vegetation, drainage network).

b) The geographical location of Benin (proximity to other producing countries such as Niger, Nigeria, Burkina Faso and other countries onion importers like Togo).

In addition to the natural potential, certain provisions promote onion production in Benin. We can talk about:

a) Mechanized irrigation through pumps for irrigation, from the shallow groundwater.

b) Interventions of many projects to support the intensification and promotion of fruit and vegetable crops.

c) Applied search to identify ways of improving vegetable production.

d) The producer’s enthusiasm for onion cultivation due to its high profitability.

e) The supply in specific inputs (Improved seeds, products pesticides, fertilizers...) from the 2000s.

f) Existence of market garders communal groups.

g) The existence of an international market and many village markets.

Especially for urban producers surveyed (Cotonou, Seme- Kpodji and Grand Popo) these are the following benefits that motivate these market gardeners to engage in the cultivation of onion.

a) The high financial profitability of onion production

b) More favorable conditions for the intensification of production systems, due to land pressure and pluriactivity that promote the enhancement of complementarities.

c) The geographical proximity to markets (Dantokpa market for example) reduces transportation costs compared to remote rural areas.

d) The reduction of energy and time in getting goods to consumers: transport, storage, especially for fresh produce.

e) The reduction of post-harvest losses due to the proximity of production areas.

f) Better product quality in terms of freshness for perishable products.

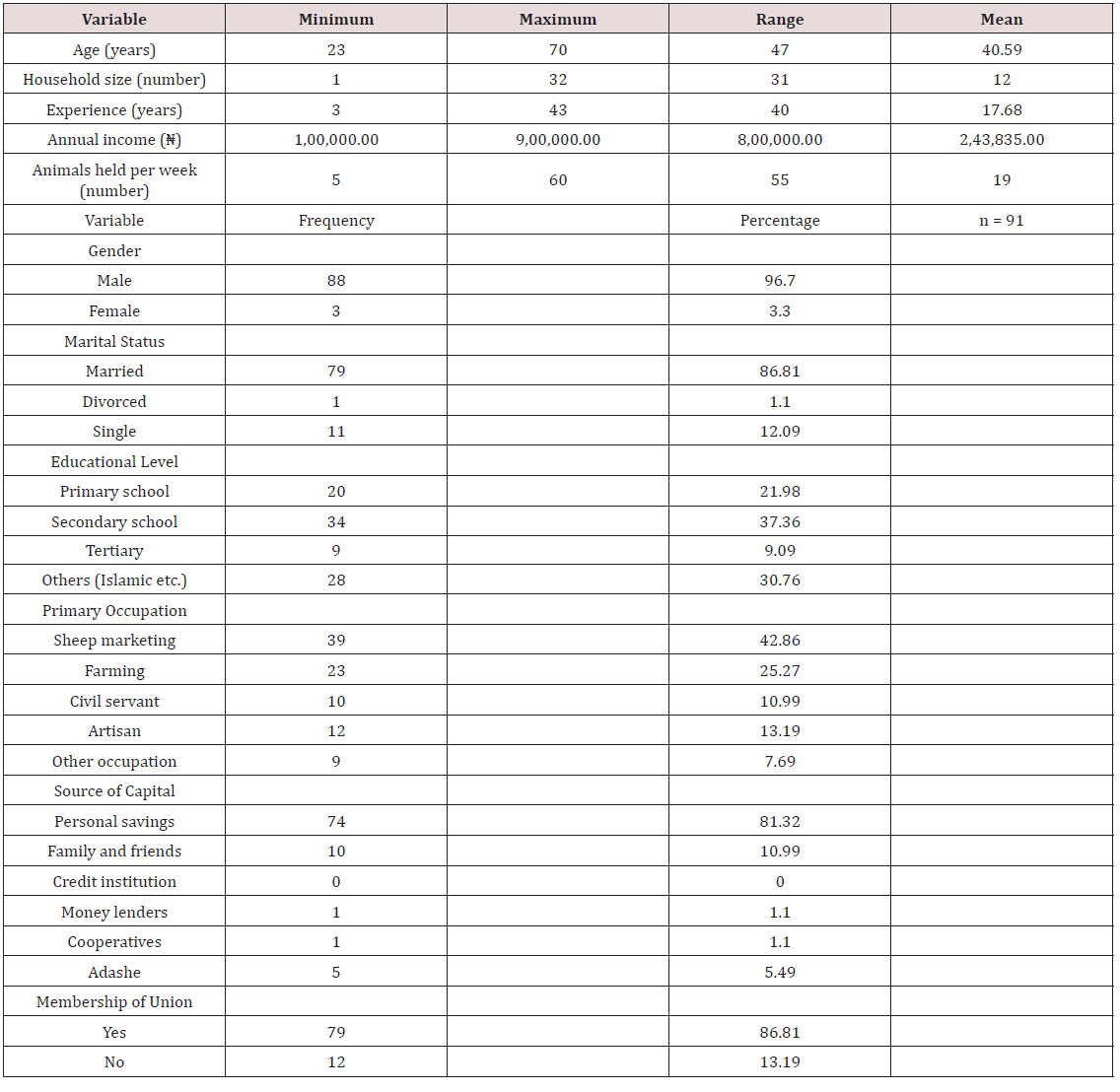

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the surveyed producers

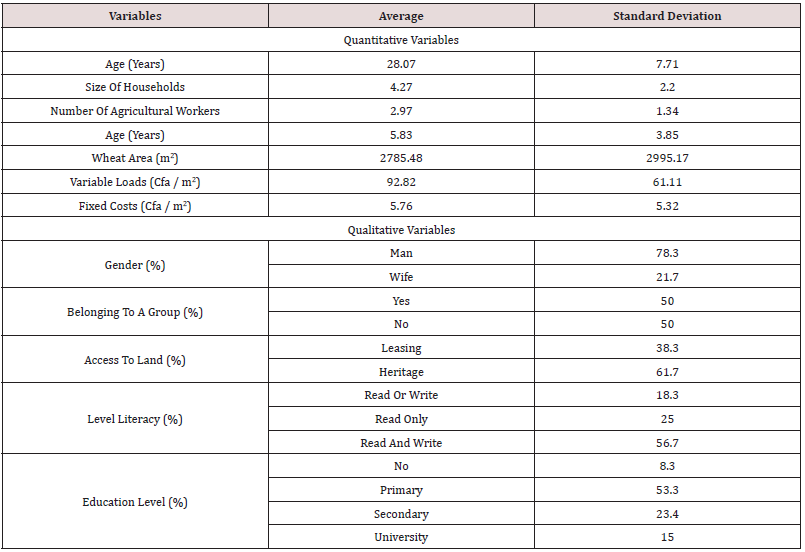

In southern Benin, specifically in the municipalities of Grand-Popo, Sèmè-Kpodji, and Cotonou onion production is predominantly male (78.3% of men against 21.7% of women). These producers have an average age of 28 (±08) with a tenure of 06 years (±04). Moreover, in the study area average household has 04 persons (±02) and 03 (±01) agricultural assets. Levels of literacy and education of the surveyed producers are more or less acceptable in public Grand-Popo, Sèmè-Kpodji and Cotonou. Note also that 50% of producers are active members of a group against a second half not belonging to a producer group. Overall, there are 81.7% literate farmers and 91.7% educated farmers. In the study zone, onion producers have an average area under crop of 2785.48 m2. These areas are obtained either legacy (61.7%) or rent (38.3%). To operate their farms, producers face two types of loads in their exploitations. These called ‘’variables’’ and those ‘’fixed’’. These charges are respectively 93 CFA/m2 and 5.76 CFA/m2. Table 5 shows the statistical variables characterizing respondents.

Source: Results of investigation, 2018.

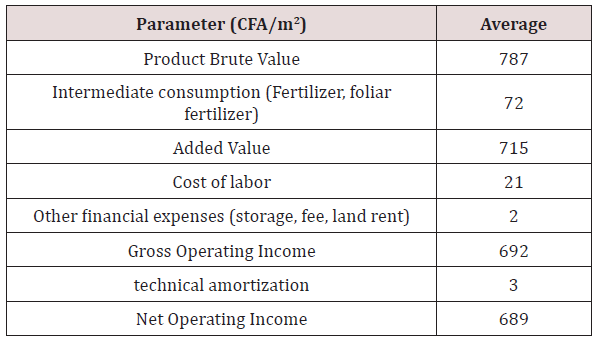

Financial Performance of onion production

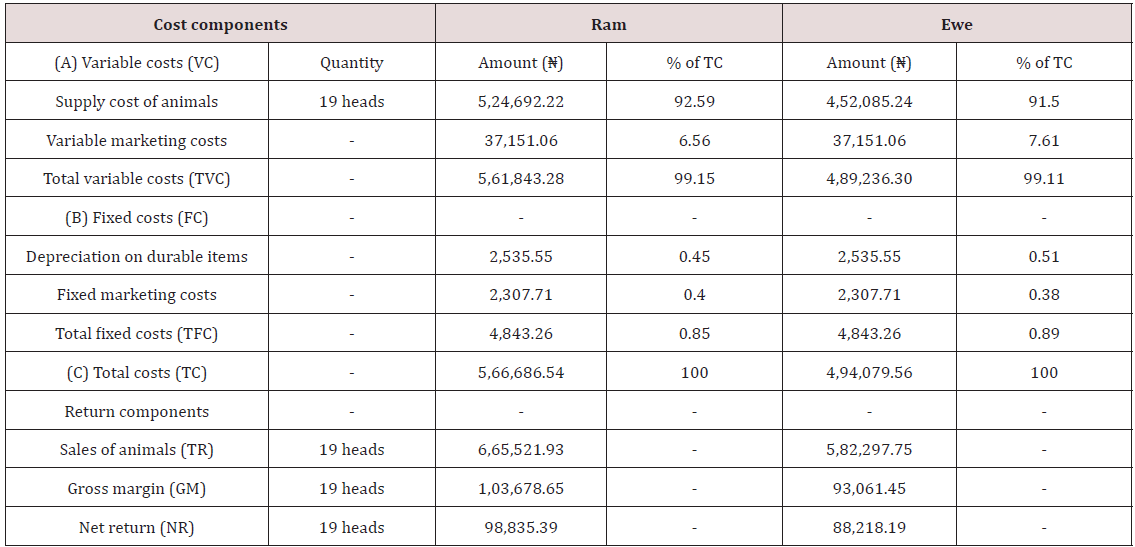

To assess the financial performance of onion production, analysis of operating farmers account was made. Thus, the results of the analysis reported in Table 4 shows that onion production is profitable in southern Benin as the average Net Operating Income calculated is positive (689 CFA/m2>0). These results are consistent with those of MAHRH [35] and Fanou [36] whose studies finally led to the conclusion that onion production is profitable. Table 6 below shows the operating account of onion producers. Note that the financial performance indicators used were calculated in CFA/m2.

Source: Results of investigation, 2018.

Determinants of onion production profitability

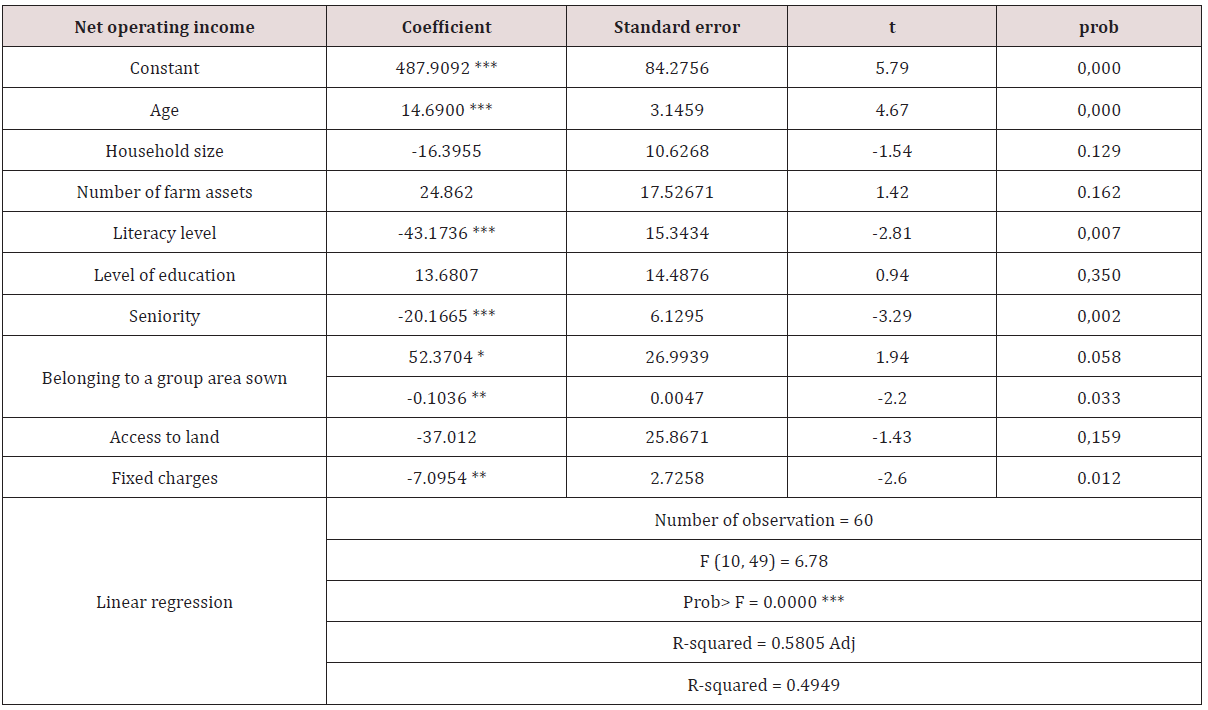

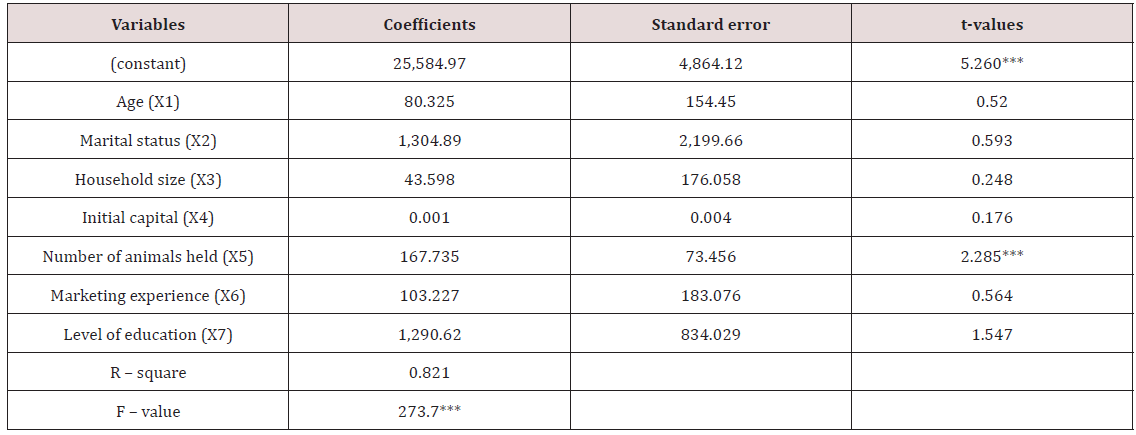

The multiple linear regression model performed to identify the determinants of the onion production profitability is generally significant at the 1% level (p=0.0000<1%). Variables such as age of the producer, the cultivated area, the level of literacy, membership in a group, the experience, and fixed costs are those which influence the onion production profitability in southern Benin. The variables of the model that are not significant are: household size, the number of farm assets, access to land and the level of producer instruction. Age has a positive significant effect on the threshold of 1% on the profitability of onion production. We therefore deduce that more the producer is old, more sometimes he took advantage of its business. The producer thus gains experience with time. Which experience allows him to improve the financial performance of his exploitations? However, these producers are very few open to new technologies that are proposed to improve their income. They therefore remain conservative. This conclusion stems from the fact that seniority has a negative significant effect on the threshold of 1% on the profitability of onion production. It is the same for literacy that has a negative and significant effect on the threshold of 1% on the profitability of onion production in southern Benin. These results are contrary to those obtained by Labiyi [37] which identify education as a determinant of economic efficiency of resource allocation in soybean production in Benin. Membership of the producer group has a positive and significant effect at the 10% threshold on the profitability of onion production.

Thus, onion producers who are members of a group have higher net profits than the others because they will benefit from certain advantages. We can highlight the sharing of information, mutual assistance and the expertise that a producer can take the other being a member of an onion producer group. These results are consistent with those of Tovignan [26] who found that producers who are members of a group have a higher net profit than others who do not belong to any group. Unlike the membership of a producer group, the wheat area has a negative and significant effect on the threshold 5% on the profitability of his exploitations. Thus, over the cultivated area, the less the onion producer benefits from his activities. The producers do not manage to meet the obligations belong to large farms. Note that these results contradict those obtained by Tovignan [26] who deduced that producers who have a large area under cotton production have a higher net profit than those having a small area. It is the same for the fixed charges that have a negative effect and significant at the 5% level on the profitability of the production of onion. Therefore, the more these expenses amounted less the producer benefits from his plantation. Table 7 shows the results of estimation of multiple linear regression model performed.

*** = Significant at 1%; ** = significant at 5%; * = Significant at 10%

Source: Estimation Results, 2018.

Source: Estimation Results, 2018.

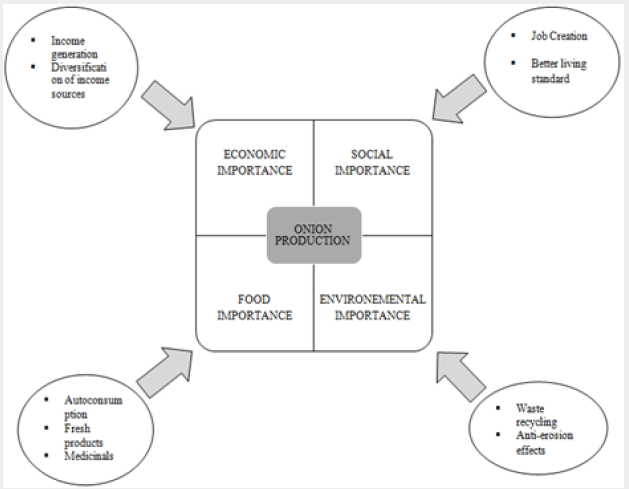

Onion importance for farmers: The onion producers constitute the largest actors group in the in the sector. Therefore, this production contributes to job creation for over 75% of agricultural assets during market gardening seasons in different regions of the study area. At the household level, onion cultivation is an important source of income and contributes to food and income security for producers. The onion is often the biggest source of cash income and helps to meet the needs of families. At Grand-Popo, as in all the investigated cities (Cotonou, Seme-Kpodji), deferred selling garden products, particularly onion is a powerful lever to support the food security of urban populations. As an activity of counter-season, onion belts allow producers not only to self-employed, to ensure household food security but also to receive significant revenue.

98% of surveyed producers recognized that onion production has resulted in many changes in their socio-economic life. In general, improving purchasing power has had a positive impact on food security, education and health situation of farmers. The onion income often also generates new income-generating activities such as petty trading, farming and others. Culturally, onion helps to prepare for marriage or pilgrimage to Mecca. Woman A and Man B two onion producers of Grand Popo and Cotonou asserted: ‘Onion production is very important to us. With this production I am more and more autonomous. I depend less on my husband. I don’t expect him anymore before buying coal or kitchen utensils. I do all my small expenses through this production income and I can even pay my tontine which was very difficult for me when I was not market gardner’ (A).’Onion is very profitable. I produce a lot of vegetables but little counter-season onion i produce, I can invest in my livestock and it is the same money that allow me paying my three children’s scholar fees each year’ (B).

Importance for input suppliers and other service providers

To carry out their activities, onion producers have much contact with a range of actors that are upstream in the value chain. Producers purchase pumps and pipes, gasoline, seeds, plows and small equipment, fertilizers and pesticides. Then, there is all kinds of economic relations between producers and suppliers, including the informal credit provision. The majority of the production costs regarding labor. Indeed, the onion sector creates many jobs, often for the poor. There is a redistribution of income from large producers to small producers, landless people in rural exodus through the agricultural labor. In most cases, producers raise funds to run production without financial institutions credit. Man C a Cotonou seed seller confirms these observations through these words:

‘In general market garden production allows us seed sellers to us to quickly sell our products in the city. Most of the time, people come to take the seeds of garden crops like onion and tomato. Many people feed through production. Carriers, agricultural equipment vendors, laborers ... ‘ (C)

Health and nutritional importance for producers-self consumer

Some market gardeners (6%) produce the onion just for its nutritional and health importance. For these producers, onion is a valuable culture that they not only produce for sale but also and especially for its therapeutic properties, organoleptic qualities and anti-erosive effect. Three onion self-consumers Men D, E and Woman F justify the importance of the Niger’s purple gold in their diet and their health situations.

‘The onion gives the taste and flavor. You can prepare a good sauce without putting a little onion. It is sometimes used to garnish the food or mitigate the effect of spicy chili’ (D)

‘The onion comes in many herbal tea in traditional therapies. When crushed with other products such as garlic, Goussi and others that can heal digestive problems, cancer, liver, rheumatism. It also helps to regulate menstruation cycle of women. My grandfather suffered from high blood pressure but with the adequate consumption of onions, it’s much better for a while ‘ (E)

‘The onion can be used in all forms: raw for salads, for example, cooked for frying or sauce, cut, beads, rapped or crushed. Onion juice can treat skin acne and provides a smooth and beautiful skin, as well as for hair growth and maintenance, colds, coughs, to sexual arousal’ (F). Figure 3 presents the advantages of onion production in southern Benin.

Figure 3: Importance of onion production in southern Benin.

Source: RResults of investigation, 2018.

Obstacles and expectations of onion producers in south benin

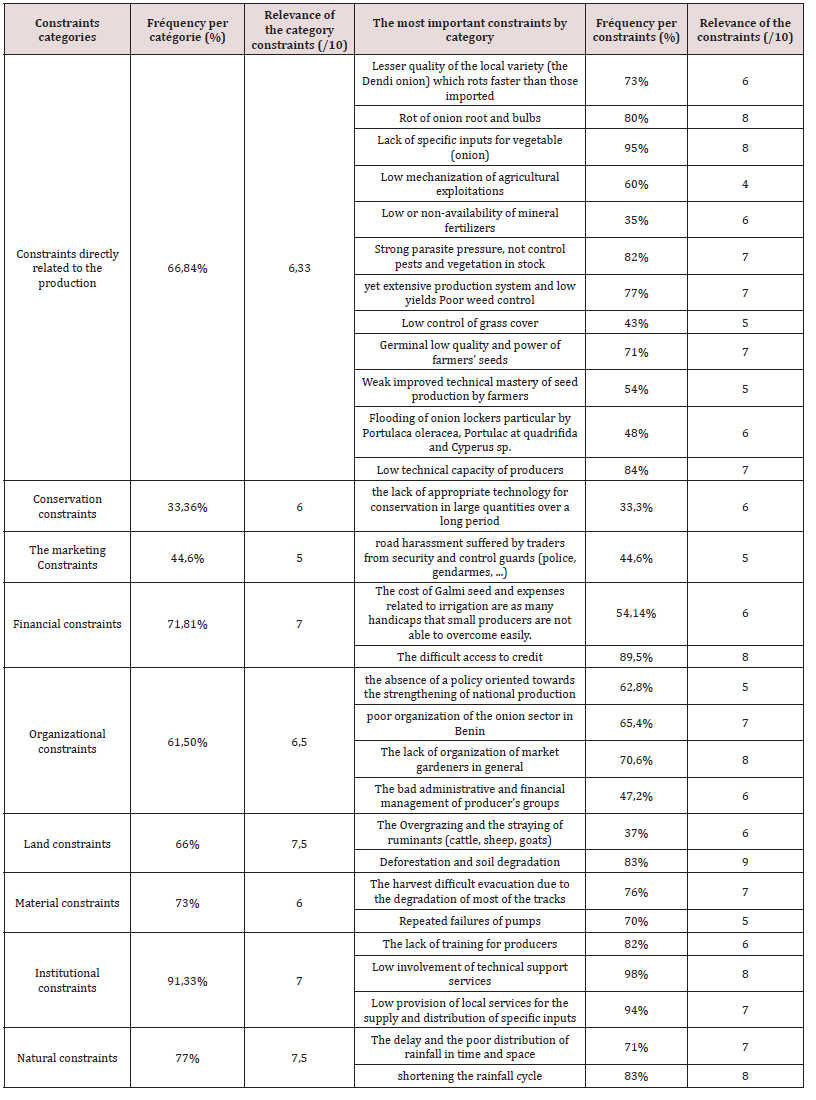

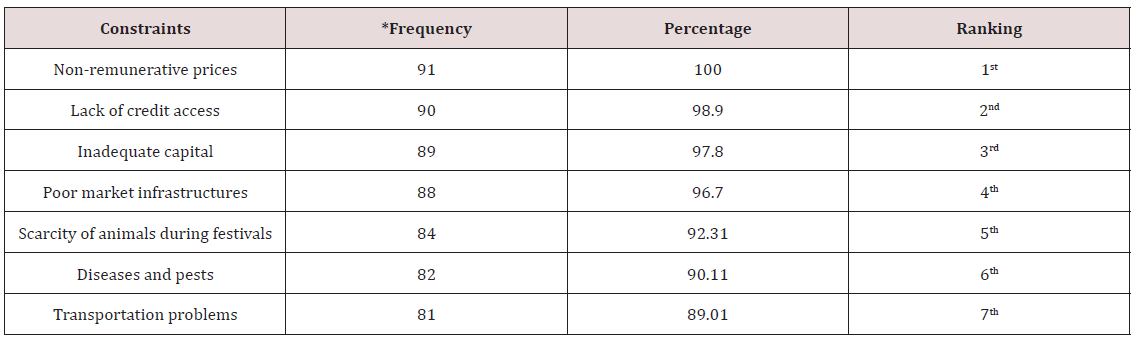

Onion production despite the many benefits that it brings to market gardeners, is facing various difficulties. Analysis of the Table 8 shows that the major constraints identified in onion production in southern Benin are institutional organizational, financial, land orders, and those directly related to production. The market gardeners interviewed affirmed that these constraints were also those for which it was essential that one find solutions. Among the most relevant constraints mentioned by farmers are: the lack of specific inputs for vegetable (onion), strong parasite pressure not control pests and vegetation in stock, the still extensive production system and low yields, low technical capacity of producers, difficult access to credit, poor organization of the onion sector in Benin, the lack of organization of market gardeners in general, deforestation and soil impoverishment, difficult harvest evacuation due to the degradation of most of the tracks, the low involvement of technical extension services, low supply of local services for the supply and distribution of specific inputs, lack of arable land, delay and poor distribution of rainfall in time and space and finally shortening the rainfall cycle.

Source: Results of investigation, 2018.

These results are in the same direction as those obtained by Gotoechan-Hodonou [38] in northern Benin, attic of the onion production. Baco [31] also identified similar constraints in their studies in the field of seed production. The context of the difficulties faced by onion farmers in southern Benin is similar to the case of Niger where the constraints identified were the poor quality and availability of inputs and equipment, problems of access to certified seeds, low financial capacity producers, poor access and insufficient agricultural credit, poor mastery of production techniques, a lack of modern storage infrastructure and huge losses in stock, the traditional character of the transformation, the lack of appropriate packaging the variability of the weight of the bag, the existence of different methods of fixing and price volatility, weak infrastructure and road harassment [39], market saturation after the third cycle of production, the lack of regulatory mechanism supply and demand and competition from foreign imports in the sub-region39. However, among the identified constraints, are institutional, organizational and financial coming to the forefront. It is therefore imperative that the public and private agricultural institutions orient their policies in a process of facilitation and development of onion production in Benin. Despite the efforts, the producers of South Benin still face enormous difficulties that significantly hamper production. Producers have issued many approaches that could improve production conditions and therefore their living conditions. The most important approaches proposed by the producers were related to the main constraints mentioned. Man X and Woman Y, two onion producers argued about it, respectively:

‘We know that we are in cities, so with regard to the land is lacking but we did not complain too much. But there are things the government can do to make our job easier. For example, they can create agricultural credit services for onion producers, they can put us in group; can also be formed on the most effective technologies of production. It is necessary that the state helps.’ (X)

‘It is difficult to produce in cities, but we mostly need help. We receive no government support. Nobody supervises us, we cope alone. We would like the state begins to take us for help. The state focuses on cotton or cashew forgetting that gardening provides food security especially those urban populations. I don’t know if they know but especially gardening onion production is more profitable than cotton. I have produced cotton in the North before coming south for work. But finally I gave myself to the production of onion because it gives me more revenue especially against season. I strongly urge agricultural institutions to find us improved varieties of onion seeds, financing for irrigation and the launch of activities, organizing into cooperatives and especially we organize training courses.’ (Y)

Conclusion

Onion production is a very important sector which may be considered not only to ensure food security of urban populations but also to improve the living conditions of the producers. This production proves very financially profitable for producers in southern Benin. In addition to its financial performance, it also impacts on social, health, nutritional and environmental producers living. It allows a large number of producers and a considerable number of actors as service providers to have substantial income. However, it would be interesting for agricultural policies to develop actions to limit constraints of this production in southern Benin.

Read More Lupine Publishers Agriculture Journal Articles: