To identify the effect of risk factors on diabetic patients. a study

was conducted among diabetic patients attending the outdoor

at the Sheikh Zaid Hospital, Lahore. Data was collected by interviewing

the patients using a structured questionnaire after the

approval of synopsis. SPSS 23.0 was used for data entry and analysis. A

sample of 100 respondents was selected by nonprobability

convenient sampling. The risk factors were analyzed in a gender study of

100. Tabular form was used to represent the

finding. Graphs shows the response of respondents. The Chi-Square test

has been used to assess the statistical significance of risk

factors for the diabetic patients. The check the normality of risk

factors and then apply Mann-Whitney test to check the effect of each

risk factor on diabetic patients w.r.t gender and marital status. The

result found that in sheikh Zaid hospital patients only physical

exercise, complications and environmental factors are affected in

diabetic patients.

Keywords: Diabetic patient; questionnaire; risk factors; chi square test; mann whitney test

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus

The word “diabetes” stems from a Greek term for passing through, a

reference to increased urination (polyuria), a common symptom of the

disease. “Mellitus” is the Latin word for honeyed, a reference to

glucose noted in the urine of diabetic patients. Diabetes mellitus is

sometimes referred to as sugar diabetes but usually is simply called

diabetes. Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease caused by inherited or

acquired deficiency of insulin production or resistance to action of the

produced insulin. Diabetes occurs when the pancreas does not produce

enough insulin (a hormone that regulates blood sugar) or alternatively,

when the body cannot effectively use the insulin it produces. The

overall risk of dying among people with diabetes is at least double the

risk of their peers without diabetes (Setter et al., 2000). Insulin is

more of an anabolic hormone rather than catabolic. Insufficient amounts

of insulin or poor cellular response to insulin as well as defective

insulin leads to improper handling of glucose by body cells or

appropriate glucose storage in the liver and muscles. This ultimately

leads to persistently high levels of blood glucose, poor protein

synthesis, and other metabolic derangements. When there will be no

insulin production or insulin become resistant then glucose will not be

supply to the cells and remain as it is in the body. When it will not

utilize by the cells then glucose level elevates in the body and cause

hyperglycemic conditions in the body and the person is said to be

diabetic. Following may be the reason of increased level of glucose in

diabetic patients

- No production of insulin by pancreas

- Not enough insulin production that help in glucose supply to the cells

- Misfunctioning of insulin known as insulin resistance

The disease has been considered as one of the major health concerns

worldwide today. The increase in incidence of diabetes in developing

countries follows the trend of urbanization and lifestyle changes,

perhaps most importantly diet [1]. Diabetes Mellitus is the common

endocrine disease and affects nearly 10% of world population. At

present, 347 million people worldwide have diabetes. In 2004, an

estimated 3.4 million people died from consequences of fasting high

blood sugar. A similar number of deaths have been estimated for 2010.

More than 80% of diabetes deaths occur in low- and middle-income

countries . Many experts continued to advise strict carbohydrate

restriction, with the result that most people with diabetes adopted a

high fat, low carbohydrate diet. Diabetes mellitus (DM) could be a risk

factor for the development and progression of liver disease.

- Weight loss: Overly high blood sugar levels can

also cause rapid weight loss, say 10 to 20 pounds over two or three

months-but this is not a healthy weight loss. Because the insulin

hormone is not getting glucose into the cells, where it can be used as

energy, the body thinks it's starving and starts breaking down protein

from the muscles as an alternate source of fuel.

- Hunger: Recessive pangs of hunger, another sign of

diabetes, can come from sharp peaks and lows in blood sugar levels. When

blood sugar levels plummet, the body thinks it has not been fed and

craves more of the glucose that cells need to function.

- Slow healing: Infections, cuts,

and bruises that do not heal quickly are another classic sign of

diabetes. This usually happens because the blood vessels are being

damaged by the excessive amounts of glucose traveling the veins and

arteries. This makes it hard for blood-needed to facilitate healing-to

reach different areas of the body.

- Increased urination, excessive thirst:

If you need to urinate frequently-particularly if you often must get up

at night to use the bathroom-it could be a symptom of diabetes. The

kidneys kick into high gear to get rid of all that extra glucose in the

blood, hence the urge to relieve yourself, sometimes several times

during the night. The excessive thirst means your body is trying to

replenish those lost fluids.

- Causes of diabetes:

The causes of diabetes are complex and only partly understood. This

disease is generally considered multifactorial, involving several

predisposing conditions and risk factors. In many cases genetics, habits

and environment may all contribute to a person’s diabetes. Weight and

body type, Family medical history, Lack of physical activity,

Carbohydrate intake, Chemical exposure, Smoking, Alcohol intake. This is

blamed largely on the rise of obesity and the global spread of

Western-style habits: physical inactivity along with a diet that is high

in calories, processed carbohydrates, and saturated fats and

insufficient in fiber rich whole foods. The aging of the population is

also a factor. However, other factors, such as environment may also be

contributing, because cases of autoimmune diabetes (type 1) are also

becoming more common [2-10]. Experts are urging people to help stem this

epidemic by getting regular exercise and controlling their diet and

weight. Humans are not the only species that can develop diabetes. This

disease also occurs in dogs, cats and other animals, as increasing

numbers of pet owners are discovering.

Diabetic complications

The direct and indirect effects on the human vascular tree are the

major source of morbidity and mortality in both type 1 and type 2

diabetes. Generally, the injurious effects of hyperglycemia are

separated into macrovascular complications (coronary artery disease,

peripheral arterial disease, and stroke) and microvascular complications

(diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy). More than half of

all individuals with diabetes eventually develop neuropathy. Long-term

metabolic complications of diabetes mellitus include retinopathy,

nephropathy, peripheral neuropathy, amputations, and Charcot joints as

well as autonomic neuropathy causing gastrointestinal, genitourinary,

cardiovascular symptoms and sexual dysfunction. Diabetics are also at a

greater risk atherosclerotic, cardiovascular, peripheral arterial and

cerebrovascular disease. Hypertension and abnormalities of lipoprotein

metabolism also accompany uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. These

cardiovascular disorders are the leading cause of death in people with

diabetes. Diabetes is the chief cause of end-stage renal disease, which

requires treatment with dialysis or a kidney transplant. These include

diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma and cataracts. Diabetes is a leading

cause of visual impairment and blindness. This includes peripheral

neuropathy, which often causes pain or numbness in the limbs, and

autonomic neuropathy, which can impede digestion (gastroparesis) and

contribute to sexual dysfunction and incontinence. Neuropathy may also

impair hearing and other senses. Many studies have linked diabetes to

increased risk of memory loss, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and other

cognitive deficits. Recently some researchers have suggested that

Alzheimer’s disease might be “type 3 diabetes,” involving insulin

resistance in the brain. Foot conditions and skin disorders, such as

ulcers, make diabetes the leading cause of nontraumatic foot and leg

amputations. People with diabetes are also prone to infections including

periodontal disease, thrush, urinary tract infections and yeast

infections [11-16]. Diabetes increases the risk of malignant tumors in

the colon, pancreas, liver and several other organs. Conditions ranging

from gout to osteoporosis to restless legs syndrome to myofascial pain

syndrome are more common in diabetic patients than nondiabetics.

Diabetes increases the risk of preeclampsia, miscarriage, stillbirth and

birth defects. Many but not all the studies exploring connections

between diabetes and mental illness have found increased rates of

depression, anxiety and other psychological disorders in diabetic

patients. In addition to chronic hyperglycemia, diabetic patients can

experience acute episodes of hyperglycemia as well as hypoglycemia (low

glucose).

Gestational diabetes

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as any degree of

glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy.

The definition applies whether insulin or only diet modification is used

for treatment and whether the condition persists after pregnancy.

Approximately 7% of all pregnancies are complicated by GDM, resulting in

more than 200,000 cases annually.

Type 1 diabetes

In type 1 diabetes, hyperglycemia occurs because of a complex disease

process where genetic and environmental factors lead to an autoimmune

response that remains to be fully elucidated. During this process, the

pancreatic B-cells within the islets of Langerhans are destroyed,

resulting in individuals with this condition relying essentially on

exogenous insulin administration for survival, although a subgroup has

significant residual C- peptide production. Type 1 diabetes is a disease

in which the pancreas does not produce any insulin. Insulin is a hormone

that helps your body to control the level of glucose (sugar) in your

blood. Without insulin, glucose builds up in your blood instead of being

used for energy. Your body produces glucose and gets glucose from foods

like bread, potatoes, rice, pasta, milk, and fruit. An autoimmune

disease in which the immune system mistakenly destroys the

insulin-making beta cells of the pancreas. It typically develops more

quickly than other forms of diabetes. It is usually diagnosed in

children and adolescents, and sometimes in young adults. To survive,

patients must administer insulin medication regularly. This form of

diabetes previously encompassed by the terms insulin–dependent diabetes,

Type 1 diabetes, or juvenile– onset diabetes, results from autoimmune

mediated destruction of the beta cells of the pancreas. The rate of

destruction is quite variable, being rapid in some individuals and slow

in others. The rapidly progressive form is commonly observed in

children, but also may occur in adults. The slowly progressive form

generally occurs in adults and is sometimes referred to as latent

autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) [17-26]. Markers of immune

destruction, including islet cell autoantibodies, and/or autoantibodies

to insulin, and autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) are

present in 85–90 % of individuals with Type 1 diabetes mellitus when

fasting diabetic hyper glycaemia is initially detected.

Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is the result of failure to produce sufficient

insulin and insulin resistance. Elevated blood glucose levels are

managed with reduced food intake, increased physical activity, and

eventually oral medications or insulin. Type 2 diabetes is believed to

affect more than 15 million adult Americans, 50% of whom are

undiagnosed. It is typically diagnosed during adulthood. However, with

the increasing incidence of childhood obesity and concurrent insulin

resistance, the number of children diagnosed with type 2 diabetes has

also increased worldwide Type 2 diabetes is Caused by insulin resistance

in the liver and skeletal muscle, increased glucose production in the

liver, over production of free fatty acids by fat cells and relative

insulin deficiency. Insulin secretion can be decreases with gradual

failure of beta cells.

Contributing factors of type 2 diabetes: Obesity,

Age (onset of puberty is associated with increased insulin resistance)

Lack of physical activity, Genetic predisposition, Racial/ethnic

background (African American, Native American, Hispanic and

Asian/Pacific Islander), Conditions associated with insulin resistance,

(e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome).

Causes of type 2 diabetes: Obesity,

Excess glucorticoid, Excess growth hormone, Gestational diabetes,

Polycystic ovary disease, Lipodystrophy, Mutation of insulin receptor,

Hemochromatosis, Blurry vision, Tingling or numbness. The most

significant contributors to or causes of type 2 diabetes are diet and

exercise. Obesity is a major risk-factor for diabetes.

Blurry vision: Having distorted vision and seeing

floaters or occasional flashes of light are a direct result of high

blood sugar levels. "Blurry vision is a refraction problem. Diabetes

mellitus is group of metabolic disorders characterized by hyper

glycemia, glycosuria and hyperlipemia”. In 2000 almost 177 million

inhabitants of the world were affected by diabetes and in future (2025)

predictable range of the people which are going to effect by the

diabetes is 300 million. Type 2 diabetes is the type of diabetes in

which insulin is produced but cells don’t take insulin for glucose

uptake. Inactive sittings, fatness is the main cause of type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes is a global problem, and its occurrence is continuously

increasing in the world. Pakistan is at 7th rank in list of countries

and it expected to have on 4th rank in future. Therefore, for research

purpose diabetes is selected because the ratio of this disease is

continuously increasing. Serum samples were collected from Sheik Zayed

hospital Lahore because this hospital was nearer to Punjab University

Lahore and have a separate diabetes department.

Methodology:

Study design: It was a cross-sectional study.

Setting: The Study was conducted at Diabetes Centre, Sheikh Zaid Hospital Lahore.

Selection of hospital: Shaikh Zayed

Hospital is a tertiary care hospital located in Lahore, Punjab,

Pakistan. It is attached with Shaikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Al-Nahyan Medical

and Dental College as a teaching hospital and is part of Shaikh Zayed

Medical Complex Lahore. And hospital is under Government of Pakistan.

Their management will be very fine as compared other government

hospitals. People believes that hospital is better than other so mostly

people are coming in this hospital for their treatments so that why I

use this hospital.

Target Population: All the patient came to the outpatient diabetes department of Sheikh Zaid Hospital Lahore. Who have Type 2 diabetes?

Duration of study: The duration of study was two months (02-05-2018 to 02-07-2018) after the approval of synopsis.

Sample Selection: Sample selection

is one of the most vital steps for conducting a research. As the

conclusion of the study is based on sample and all the inference are

consequently referred to whole the population it should be a good

representative to the target population.

Sampling technique: Non-probability convenient sampling technique was used for collection of data.

Sample size: 1000 cases were used in this study.

Data collection procedure: The

success of the survey depends upon accuracy of the data collection. The

correction of the accurate data depends upon the correct choice of

survey method. After questionnaire, the next step was data collection.

Face to face method was used for the collection of data keeping in mind

the difficulty of locating the respondent after giving them the

questionnaire. So, it was the best way to give the questionnaire to the

respondent and be there for a while until the respondent fill and give

it back. Respondent asks the purpose of the survey, meaning of the

questions which they do not completely understand. Data were collected

by suing a Performa/Questionnaire. The first part of the Performa

contained information’s about the demographic characteristic of the

patients while the second part contained information regarding risk

factors of the disease. The collection of the accurate data depends upon

the careful construction of a tool of data collection. There are some

difficulties in field experience [27-34]. The respondent’s behavior was

good, but some respondents refused to fill up the questionnaire. After

explaining the objective of the study, they agreed to cooperate. Though

at some places of the behavior of the respondents were not encouraging

but it was a great experience overall.

- Inclusion criteria: The patient came to the outpatient diabetes department agreed to provide information.

- Exclusion criteria: Patients who are not agreeing to provide information.

Data Analysis:

Software package: Data were entered and analyzed by using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) version 23.

Statistical Technique

- Descriptive Analysis: For descriptive of variables

frequency were shown in tables. Charts and graphs were given for

percentages in qualitative variables.

- Analytical Analysis: To find the risk variable of diabetes gender wise the current section is divided in the two main components.

- Bivariate Analysis

- Logistic Regression

Results

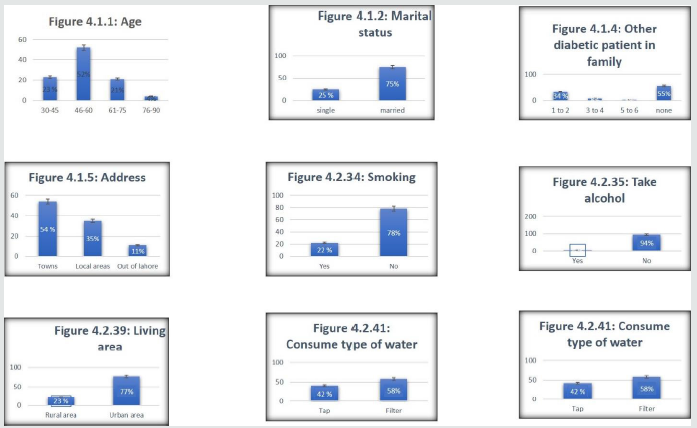

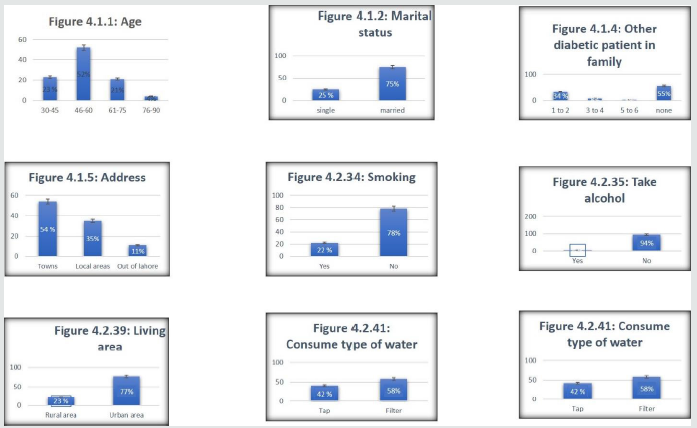

Figure 1: Shows the perecentage variation among the diabetic patients with various factors from figure 4.1.1 to 4.2.41.

This study consists of 1000 subjects in which both male and female

are included. There are 53 variables age, other diabetic patients in

family, family members, address, marital status, gender, regarding

follow doctor, type of meal, skip meal, gain weight, vision problem,

wound problem, sugar fluctuation, social life, smoking, alcohol, alcohol

frequently use, sanitary area, regularly use of medicine, fact of

necessary exercise, fact of routine walk, daily walk, exercise, kind of

exercise, time of exercise, day spend in exercise, walking time, Meals,

hoteling, frequently of hoteling, use of fruits, use of milk, take care

of yourself, loss weight, kidney problem, skin problem, regularly check

sugar, sugar check time in a day, sugar record, sugar level, routine

work, hobbies, effect of diabetes, industry area, industry type, living

area, type of water, kind of medicine, use of vitamins, check-up,

discuss problem with doctor, satisfaction from treatment. Figure 1 shows

that out of 1000 respondents, 23(23.0%) persons have 30-45 age,

52(52.0%) persons have 46-60, 21(21.0%) persons have 61-75 and 4(4.0%)

persons have 76-90. Among 23 persons who have the 30-45 age, the count

(percentages) for male and female were 7(30.4%) and 16(69.6%)

respectively and among 52 persons who have the 46-60 age, the count

(percentages) for male and female were 16(30.8%) and 36(69.2%)

respectively and among 21 persons who have 76-90 age , the count

(percentages) for male and female were 4(100.0%) and 0(0.0%)

respectively . Figure 1 shows that out of 1000 respondents, 25 (25.0%)

persons have single while 75(75.0%) persons have married. Among 25

persons who are single , the count (percentages) for male and females

were 11(44.0) and 14(56.0%) respectively and among 75 persons who are

married, the count (percentages) for male and females were 28(37.3%) and

47(62.7%) respectively. Figure 1 shows that of out of 1000 respondents,

37(37.0%) persons have 1-5 family members, 47(47.0%) persons have 6-10

family members, 12(12.0%) have 11-15 family members and 4(4.0% have

16-20 family members. Among 37 persons have 1-5 family members, the

count (percentages) for male and females were 18(49.6%) and 19(51.4%)

respectively and among 47 persons have 6-10 family members, the count

(percentages) for male and females were 19(40.4%) and 28 (59.6%)

respectively and among 12 persons have 11-15 family members, the count

(percentages) for male and females were 1(8.3%) and 11(91.7%)

respectively and among 4 persons have 16-20 family members, the count

(percentages) for male and females were 1(25.0%) and 3(75.0%). Figure 1

shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 34(34.0%) persons have 1-2

diabetic patient in family members, 8(8.0%) persons have 3-4 diabetic

patient in family members, 3(3.0%) have 5-6 diabetic patient in family

members and 55(55.0%) have no diabetic patient in family members. Among

34 persons have 1-2 diabetic patient in family members, the count

(percentages) for male and females were 12(35.3%) and 22(64.7%)

respectively and among 8 persons have 3-4 diabetic patient in family

members, the count (percentages) for male and females were 0(0.0%) and

8(100.0%) respectively and among 55 persons have no diabetic patient in

family members, the count (percentages) for male and females were

27(49.1%) and 28(50.9%) respectively [35-46]. Figure 1 shows that of out

of 1000 respondents, 54(53.0%) persons address of towns, 3535.0%)

persons have address of local areas and 11(11.0%) persons address out of

Lahore. Among 54 persons address of towns, the count (percentages) for

male and females were 20(37.0%) and 34(63.0%) respectively and among 35

persons address of local areas, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 16(45.7%) and 19(54.3%) respectively and among 11 persons

address of out of Lahore, the count (percentages) for male and females

were 3(27.3%) and 8(72.7%) respectively Figure 1 shows that of out of

1000 respondents, 22(22.0%) persons that are doing smoking and 78(78.0%)

persons that are not doing smoking. Among 22 that are doing smoking,

the count (percentages) for male and female were 20(90.0%) and 2(9.1%)

respectively and among 78 persons that are not doing smoking, the count

(percentages) for males and females were 19(24.4%) and 59(75.6%)

respectively Figure 1 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 6(6.0%)

persons that are taking alcohol and 94(94.0%) persons that are not

taking alcohol. Among 6 that are taking alcohol, the count (percentages)

for male and female were 6(100.0%) and 0(0.0%) respectively and among

94 persons that are not taking alcohol, the count (percentages) for

males and females were 33(35.1%) and 61(64.5%) respectively Figure 1

shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 23(23.0%) persons that are living

in rural area and 77(77.0%) persons that are living in urban area

[47-53]. Among 23 that are living in rural area, the count (percentages)

for male and female were 6(26.1%) and 17(73.9%) respectively and among

77 persons that are living in urban area, the count (percentages) for

males and females were 33(42.9%) and 44(57.1%) respectively. Figure 2

shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 27(27.0%) persons that their area

sanitary system is very good and 45(45.0%) persons that their area

sanitary system is good and 17(17.0%) persons that there are a sanitary

system is bad and 11(11.0%) persons that their area sanitary system is

very bad. Among persons that their area sanitary system is very good,

the count (percentages) for male and female were 4(14.8%) and 23(85.2%)

respectively and among 45 persons that their area sanitary system is

good, the count (percentages) for males and females were 27(60.0%) and

18(40.0%) respectively and among persons that there are a sanitary

system is bad, the count (percentages) for male and female were 7(41.2%)

and 10(58.8%) and 11 persons that their area sanitary system is very

bad, the count (percentages) for male and female were 1(9.1) and

10(90.9%) respectively Figure 1 shows that of out of 1000 respondents,

42(42.0%) persons that consume tap water and 58(58.0%) persons that are

consume filter water. Among 42 that are consume tap water, the count

(percentages) for male and female were 15(35.7%) and 27(64.3%)

respectively and among 58 persons that are consume filter water, the

count (percentages) for males and females were 24(40.0%) and 36(60.0%)

respectively. Figure 2 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 25(25.0%)

persons that are living in industrial area and 75(75.0%) persons that

are not living in industrial area. Among 26 that are living in

industrial area, the count (percentages) for male and female were

10(40.0%) and 15(60.0%) respectively and among 75 persons that are not

living in industrial area, the count (percentages) for males and females

were 29(38.7%) and 46(61.3%) respectively Figure 2 shows that of out of

1000 respondents, 80(80.0%) persons think that exercise is necessary

for diabetic patients, 17(17.0%) persons thought that exercise is not

necessary for diabetic patients and 3(3.0%) persons have no idea that

exercise is suitable or not for diabetic patients. Among 80 persons

think that the exercise is necessary for diabetic patients, the count

(percentages) for male and females were 31(38.8%) and 49(61.3%)

respectively and among 17 persons think that exercise is not necessary

for diabetic patients, the count (percentages) for male and females were

6(35.3%) and 11(64.7%) respectively and among 3 persons don’t know that

exercise is necessary for diabetic patients, the count (percentages)

for male and females were 2(66.7%) and 1(33.3%) respectively. Figure 2

shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 88(88.0%) persons think that

routine Walk is helpful for diabetic patients, 9(9.0%) persons think

that walk is not helpful for diabetic patients and 3(3.0%) persons have

no idea that walk is helpful or not. Among 88 persons think that the

routine walk is helpful for diabetic patients, the count (percentages)

for male and females were 32(36.4%) and 56(63.6%) respectively and among

9 persons think that routine is not helpful for diabetic patients, the

count (percentages) for male and females were 5(55.6%) and 4(44.4%)

respectively and among 3 persons don’t know that routine walk is helpful

or not for diabetic patients, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 2(66.7%) and 1(33.3%) respectively.

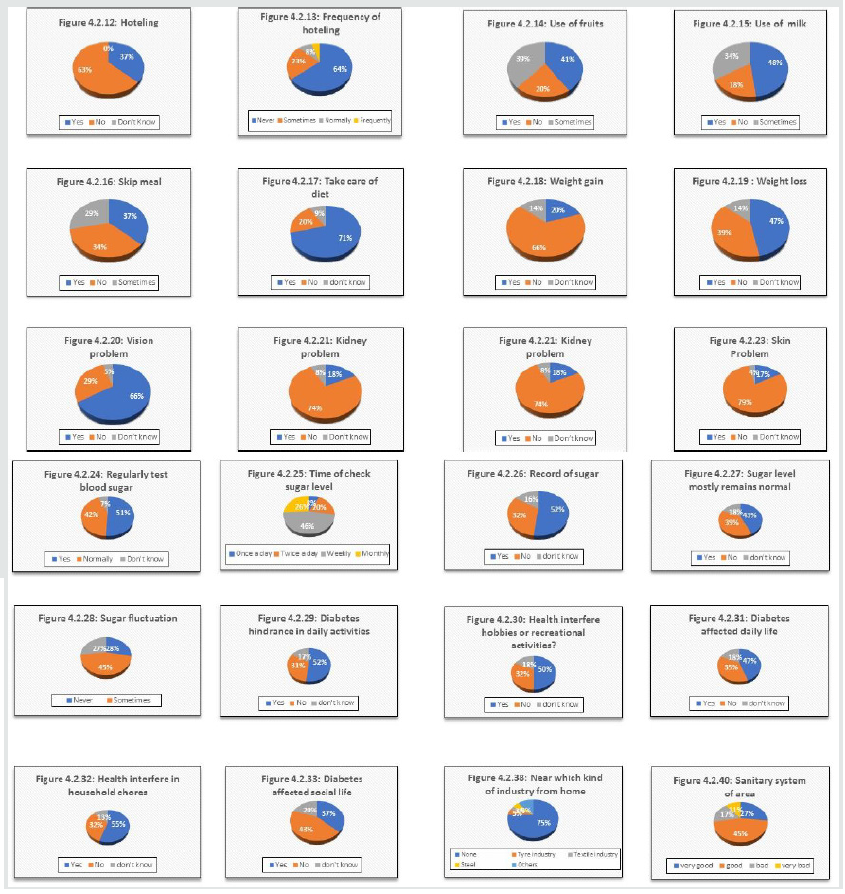

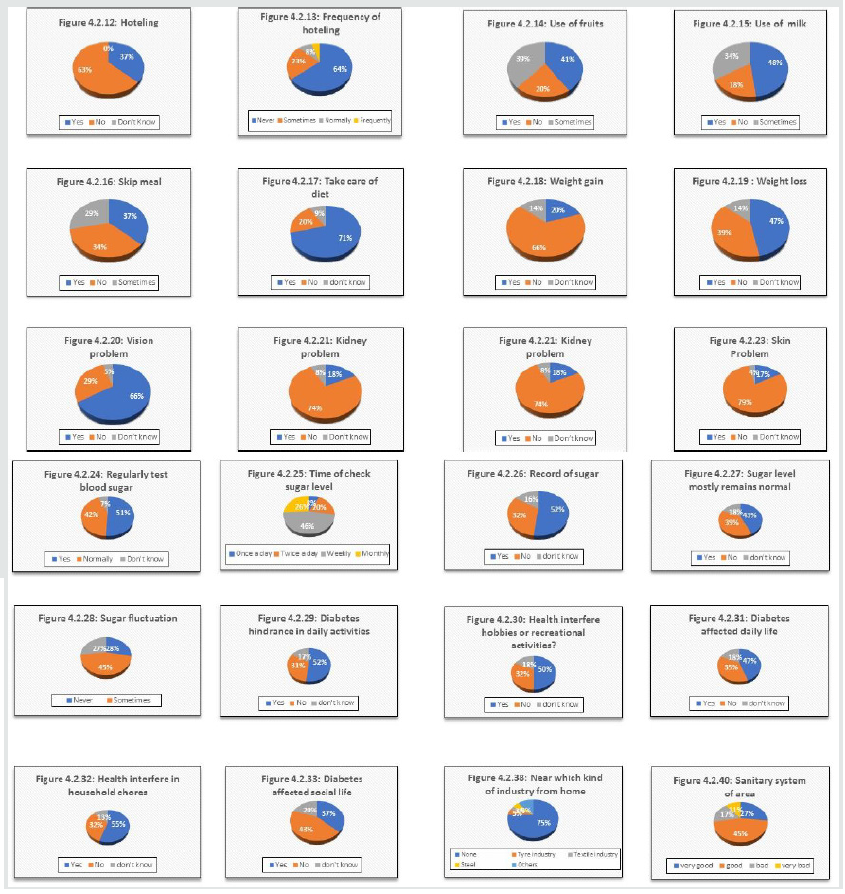

Figure 2: this shows percentage variation in pi charts form from 4.2.1 to 4.2.11.

Figure 2 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 67(67.0%) persons

follow doctor regarding to exercise, 32(32.0%) persons do not follow

doctor regarding to exercise, and 1(1.0%) persons don’t know about

follow doctor regarding to exercise. Among 67 persons follow doctor

regarding to exercise, the count (percentages) for male and females were

21(31.3%) and 46(68.7%) respectively and among 32 persons don’t follow

doctor regarding to exercise, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 18(56.3%) and 14(43.8%) respectively and among 1 persons

don’t know about follow doctor regarding to exercise, the count

(percentages) for male and females were 0(0.0%) and 1(100.0%)

respectively Figure 2 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 79(79.0%)

persons go for daily walk, 21(21.0%) persons do not go for daily walk.

Among 79 persons go for daily walk, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 34(43.0%) and 45(57.0%) respectively and among 21 persons

do not go for daily walk, the count (percentages) for male and females

were 5(23.8%) and 16(76.2%) respectively. Figure 2 shows that of out of

1000 respondents, 80(80.0%) persons follow any kind of exercise,

20(20.0%) persons do not follow any kind of exercise. Among 80 persons

follow any kind of exercise, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 31(38.8%) and 49(61.3%) respectively and among 20 persons

do not follow any kind of exercise, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 8(40.0%) and 12(60.0%) respectively Figure 2 shows that of

out of 1000 respondents, 67(67.0%) persons that follow manual exercise ,

15(15.0%) persons that follow electrical exercise and 18(18.0) persons

that don’t follow any manual or electrical exercise. Among 67 persons

that follow manual exercise, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 25(37.3%) and 42(62.7%) respectively and among 15 persons

that follow electrical exercise, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 6(40.0%) and 9(60.0%) respectively and among 18 persons

don’t follow any manual or electrical exercise, the count (percentages)

for male and females were 8(44.4%) and 10(55.6%) respectively Figure 2

shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 17(17.0%) persons that spend time

in exercise 15 min, 37(37.0%) persons that spend time in exercise 30

min, 25(25.0) persons that spend time in exercise 1 hour , 6(6.0)

persons that spend time in exercise 1.5 hour and 15(15.0) persons that

spend no time on exercise. Among 17 persons that spend time in exercise

15 min, the count (percentages) for male and females were 3(17.6%) and

14(82.4%) respectively and among 37 persons that spend time in exercise

30 min, the count (percentages) for male and females were 19(51.4%) and

18(48.6%) respectively and among 25 persons that spend time in exercise 1

hour, the count (percentages) for male and females were 9(36.0%) and

16(64.0%) respectively and among 6 persons that spend time in exercise

1.5 hour, the count (percentages) for male and females were 1(16.7%) and

5(83.3%) respectively and among 15 persons that spend no time in

exercise, the count (percentages) for male and females were 7(46.7%) and

8(53.3%) respectively

Figure 2 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 42(42.0%) persons

that spend morning in exercise, 4(4.0%) persons that spend afternoon in

exercise, 31(31.0) persons that spend evening in exercise and 23(23.0%)

persons spend no part of day in exercise. Among 42 persons that spend

morning in exercise, the count (percentages) for male and females were

15(36.7%) and 27(64.3%) respectively and among 4 persons that spend

afternoon in exercise, the count (percentages) for male and females were

2(50.0%) and 2(50.0%) respectively and among 31 persons that spend

evening in exercise, the count (percentages) for male and females were

11(35.5%) and 20(64.5%) respectively and among 23 persons spend no part

of day in exercise, the count (percentages) for male and females were

11(47.8%) and 12(52.2%) respectively. Figure 2 shows that of out of 1000

respondents, 52(52.0%) persons that spend morning for walk, 4(4.0%)

persons that spend afternoon for walk, 23(23.0%) persons that spend

evening for walk and 21(21.0%) persons spend no time for walk. Among 52

persons that spend morning for walk, the count (percentages) for male

and females were 24(46.2%) and 28(53.8%) respectively and among 4

persons that spend afternoon for walk, the count (percentages) for male

and females were 1(25.0%) and 3(75.0%) respectively and among 23 persons

that spend evening for walk, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 8(39.1%) and 14(60.9%) respectively and among 23 persons

spend no time for walk, the count (percentages) for male and females

were 5(23.8%) and 16(76.2%) respectively. Figure 2 shows that of out of

1000 respondents, 1(1.0%) persons that 1 time take meal in day,

19(19.0%) persons that 2 times take meal in a day, 71(71.0%) persons

that 3 times take meal in a day, and 9(9.0%) persons that 4 times take

meal in a day. Among 1 persons that 1 time take meal in a day, the count

(percentages) for male and females were 0(0.0%) and 1(100.0%)

respectively and among 19 persons that 2 times take meal in a day, the

count (percentages) for male and females were 8(42.1%) and 11(57.9%)

respectively and among 71 persons that 3 times take meal in a day, the

count (percentages) for male and females were 25(35.2%) and 46(64.8%)

respectively and among 9 persons that 4 times take meal in a day, the

count (percentages) for male and females were 6(39.0%) and 3(33.3%)

respectively. Figure 2 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 74(74.0%)

persons that use wheat in meal, 17(17.0%) persons that use rice in meal

and 9(9.0%) persons that use fiber in meal. Among 74 persons that use

wheat in meal, the count (percentages) for male and females were

33(44.6%) and 41(55.4%) respectively and among 17 persons that use rice

in meal, the count (percentages) for male and females were 2(11.8%) and

15(88.2%) respectively and among 9 persons that use fiber in meal, the

count (percentages) for male and females were 4(44.4%) and 5(55.6%)

respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 37(37.0%)

persons that go out for meal, 63(63.0%) persons that do not go out for

meal. Among 37 persons that go out for meal, the count (percentages) for

male and females were 15(40.5%) and 22(59.5%) respectively and among 63

persons that not go for meal, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 24(38.%) and 39(61.9%) respectively .

Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 64(64.0%) persons

that never go out for meal, 23(23.0%) persons that sometimes go out for

meal, 8(8.0%) persons that normally go out for meal, and 5(5.0%) persons

that have frequently go out for meal. Among 64 persons that never go

out for meal, the count (percentages) for male and females were

25(39.1%) and 39(60.9%) respectively and among 23 persons that sometimes

go out for meal, the count (percentages) for male and females were

7(30.4%) and 16(69.6%) respectively and among 8 persons that normally go

out for meal, the count (percentages) for males and females were

5(62.5%) and 3(37.5%) respectively and among 5 persons that frequently

go out for meal, the count (percentages) for male and female were

2(40.0%) and 3(60.0%). Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents,

41(41.0%) persons that regularly use of fruit, 20(20.0%) persons that

are not use of fruit, 39(39.0%) persons that sometimes use the fruits.

Among 41 persons that regularly use of fruit, the count (percentages)

for male and females were 16(39.0%) and 25(61.0%) respectively and among

20 persons that are not use of fruit, the count (percentages) for male

and females were 7(35.0%) and 13(65.0%) respectively and among 39

persons that sometime use of fruit, the count (percentages) for males

and females were 16(41.0%) and 23(59.0%) respectively Figure 3 shows

that of out of 1000 respondents, 48(48.0%) persons that regularly use of

milk, 18(18.0%) persons that are not use of milk, 34(34.0%) persons

that sometimes use the milk. Among 48 persons that regularly use of

milk, the count (percentages) for male and females were 21(43.8%) and

27(56.3%) respectively and among 18 persons that are not use of milk,

the count (percentages) for males and females were 4(22.2%) and

14(77.8%) respectively and among 34 persons that sometime use of milk,

the count (percentages) for males and females were 14(41.2%) and

20(58.8%) respectively Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents,

37(37.0%) persons that skip their meal, 34(34.0%) persons that are not

skip their meal, 29(29.0%) persons that response is don’t know means

that persons have not in mind that they skip meal or not in routine.

Among 37 persons that skip their meal, the count (percentages) for male

and females were 7(18.9%) and 30(81.1%) respectively and among 34

persons that are not skip their meal, the count (percentages) for males

and females were 19(55.9%) and 15(44.1%) respectively and among 29

persons that have not in mind that they skip meal or not in routine, the

count (percentages) for males and females were 13(44.8%) and 16(55.2%)

respectively.

Figure 3: This also shows the percentage variation in pi chart form from 4.2.12. to 4.2.40.

Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 71(71.0%) persons

that take of their diet, 20(20.0%) persons that are not take of their

diet, 9(9.0%) persons that response is don’t know means that persons

have not in mind that they take of diet or not. Among 71 persons that

skip their meal, the count (percentages) for male and females were

25(35.2%) and 46(64.8%) respectively and among 20 persons that are not

take of their diet, the count (percentages) for males and females were

11(55.0%) and 9(45.0%) respectively and among 9 persons that have not in

mind that they take of their diet or not, the count (percentages) for

males and females were 3(33.3%) and 6(66.7%) respectively. Figure 3

shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 20(20.0%) persons that weight

gain, 66(66.0%) persons that not weight gain, 14(14.0%) persons that

response is don’t know means that persons have not know that about their

weight that gain or not. Among 20 persons that gain weight, the count

(percentages) for male and females were 2(10.0%) and 18(90.0%)

respectively and among 66 persons that are not gain weight, the count

(percentages) for males and females were 31(47.0%) and 35(53.0%)

respectively and among 14 persons that don’t know that weight gain or

not, the count (percentages) for males and females were 6(42.9%) and

8(57.1%) respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents,

47(47.0%) persons that weight loss, 39(39.0%) persons that not weight

loss, 14(14.0%) persons that response is don’t know means that persons

don’t know that about their weight that loss or not. Among 47 persons

that loss weight, the count (percentages) for male and females were

18(38.3%) and 29(61.7%) respectively and among 39 persons that are not

lose weight, the count (percentages) for males and females were

15(38.5%) and 24(61.5%) respectively and among 14 persons that don’t

know that weight gain or not, the count (percentages) for males and

females were 6(42.9%) and 8(57.1%) respectively Figure 3 shows that of

out of 1000 respondents, 66(66.0%) persons that have vision problem,

29(29.0%) persons that have no vision problem and 5(5.0%) persons that

response is don’t know means that persons don’t know that about their

vision problem. Among 66 persons that have vision problem, the count

(percentages) for male and females were 18(27.3%) and 48(72.2%)

respectively and among 29 persons that have no vision problem, the count

(percentages) for males and females were 17(58.6%) and 12(41.4%)

respectively and among 5 persons that don’t know about their vision

problem, the count (percentages) for males and females were 4(80.0%) and

1(20.0%) respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents,

18(18.0%) persons that have kidney problem, 74(74.0%) persons that have

no kidney problem and 8(8.0%) persons that response is don’t know means

that persons don’t know that about their kidney problem. Among 18

persons that have kidney problem, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 4(22.2%) and 14(77.8%) respectively and among 74 persons

that have no kidney problem, the count (percentages) for males and

females were 30(40.5%) and 44(59.5%) respectively and among 8 persons

that don’t know about their kidney problem, the count (percentages) for

males and females were 5(62.5%) and 3(37.5%) respectively. Figure 3

shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 36(36.0%) persons that have wound

healing problem, 56(56.0%) persons that have no wound healing problem

and (8.0%) persons that response is don’t know means that persons don’t

know that about their wound healing problem. Among 36 persons that have

wound healing problem, the count (percentages) for male and females were

5(13.9%) and 31(86.1%) respectively and among 56 persons that have no

wound healing problem, the count (percentages) for males and females

were 29(51.8%) and 27(48.2%) respectively and among 8 persons that don’t

know about their wound healing, the count (percentages) for males and

females were 5(62.5%) and 3(37.5%) respectively.

Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 17(17.0%) persons

that have skin problem, 79(79.0%) persons that have no skin problem and

4(4.0%) persons that response is don’t know means that persons don’t

know that about their skin problem. Among 17 persons that have skin

problem, the count (percentages) for male and females were 5(29.4%) and

12(70.6%) respectively and among 79 persons that have no skin problem,

the count (percentages) for males and females were 32(40.5%) and

47(59.5%) respectively and among 4 persons that don’t know about their

skin problem, the count (percentages) for males and females were

2(50.0%) and 2(20.0%) respectively Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000

respondents, 51(51.0%) persons check their sugar level regularly,

42(42.0%) persons that are not check their sugar level regularly and

7(7.0%) persons that response is don’t know means that persons don’t

know that check their sugar level regularly. Among 51 persons that check

their sugar level regularly, the count (percentages) for male and

females were 15(29.4%) and 36(70.6%) respectively and among 42 persons

that are not check their sugar level regularly, the count (percentages)

for males and females were 22(52.4%) and 20(47.6%) respectively and

among 7 persons that don’t know about check their sugar level regularly,

the count (percentages) for males and females were 2(528.6%) and

5(71.4%) respectively Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents,

8(8.0%) persons check their sugar level once a day, 20(20.0%) persons

that check their sugar level twice a day, 46(46.0%) persons that check

their sugar level weekly and 8(8.0%) that check their sugar level

monthly. Among 8 persons that check their sugar level once a day, the

count (percentages) for male and female were 4(50.0%) and 4(50.0%)

respectively and among 20 persons that check their sugar level twice a

day, the count (percentages) for male and female were 7(35.0%) and

13(65.0%) respectively and among 46 persons that check their sugar level

weekly, the count (percentages) for male and female were 20(43.5%) and

26(56.5%) respectively and among 8 person that check their sugar level

monthly, the count(percentages) for male and female were 8(30.8%) and

18(69.2%) respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents,

52(52.0%) persons record their sugar level , 32(32.0%) persons that are

not record their sugar level and 16(16.0%) persons that response is

don’t know means that have not in mind that record their sugar level.

Among 52 persons that record their sugar level, the count (percentages)

for male and female were 19(36.5%) and 33(63.5%) respectively and among

32 persons that are not record their sugar level, the count

(percentages) for males and females were 16(50.0%) and 16(50.0%)

respectively and among 16 persons that don’t know means that have not in

mind that record their sugar level, the count (percentages) for male

and female were 4(25.0%) and 12(75.0%) respectively. Figure 3 shows that

of out of 1000 respondents, 43(43.0%) persons mostly their sugar level

remain normal , 39(39.0%) persons that are not their sugar level remain

normal and 18(18.0%) persons that response is don’t know means that have

not in mind that their sugar level remain normal. Among 43 persons that

their sugar level remain normal, the count (percentages) for male and

female were 18(41.9%) and 25(58.1%) respectively and among 39 persons

that are not their sugar level remain normal, the count (percentages)

for males and females were 14(35.9%) and 25(64.1%) respectively and

among 18 persons that don’t know means that have not in mind that their

sugar level remain normal, the count (percentages) for male and female

were 7(38.9%) and 11(61.1%) respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of

1000 respondents, 28(28.0%) persons never fluctuate their sugar level,

45(45.0%) persons sometimes fluctuate their sugar level and 27(27.0%)

persons every time fluctuate their sugar level Among 28 persons never

fluctuate their sugar level, the count (percentages) for male and female

were 16(57.1%) and 12(42.9%) respectively and among 45 persons

sometimes fluctuate their sugar level, the count (percentages) for males

and females were 18(40.0%) and 27(60.0%) respectively and among 27

persons that every time fluctuate their sugar level, the count

(percentages) for male and female were 5(18.5%) and 22(81.5%)

respectively.

Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 52(52.0%) persons

that agree that diabetes hindrance in daily activities, 31(31.0%)

persons that not agree that diabetes hindrance in daily activities and

17(17.0%) persons that response answer in don’t know means they have no

idea that diabetes hindrance in daily activities. Among 52 that agree

that diabetes hindrance in daily activities, the count (percentages) for

male and female were 20(38.5%) and 32(61.5%) respectively and among 31

persons that not agree that diabetes hindrance in daily activities, the

count (percentages) for males and females were 11(35.5%) and 20(64.5%)

respectively and among 17 persons that response answer in don’t know

means they have no idea that diabetes hindrance in daily activities, the

count (percentages) for male and female were 8(47.1%) and 9(53.9%)

respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 50(50.0%)

persons that agree that health interfere hobbies or recreational

activities, 32(32.0%) persons that not agree that health interfere

hobbies or recreational activities and 18(18.0%) persons that response

answer in don’t know means they have no idea that health interfere

hobbies or recreational activities. Among 50 that agree that health

interfere hobbies or recreational activities, the count (percentages)

for male and female were 16(32.0%) and 34(68.0%) respectively and among

32 persons that not agree that health interfere hobbies or recreational

activities, the count (percentages) for males and females were 16(50.0%)

and 16(50.0%) respectively and among 18 persons that response answer in

don’t know means they have no idea that health interfere hobbies or

recreational activities, the count (percentages) for male and female

were 7(38.9%) and 11(61.1%) respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of

1000 respondents, 47(47.0%) persons that agree that diabetes affected

daily life, 35(35.0%) persons that not agree that diabetes affected

daily life and 18(18.0%) persons that response answer in don’t know

means they have no idea that diabetes affected daily life. Among 47 that

agree that diabetes affected daily life, the count (percentages) for

male and female were 15(31.9%) and 32(68.1%) respectively and among 35

persons that not agree that diabetes affected daily life, the count

(percentages) for males and females were 17(48.6%) and 18(51.4%)

respectively and among 18 persons that response answer in don’t know

means they have no idea that health diabetes affected daily life, the

count (percentages) for male and female were 7(38.9%) and 11(61.1%)

respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 55(55.0%)

persons that agree that health interfere in household chores, 32(32.0%)

persons that not agree that health interfere in household chores and

13(13.0%) persons that response answer in don’t know means they have no

idea that health interfere in household chores. Among 55 that agree that

health interfere in household chores, the count (percentages) for male

and female were 16(29.1%) and 39(70.9%) respectively and among 32

persons that not agree that health interfere in household chores, the

count (percentages) for males and females were 16(50.0%) and 16(50.0%)

respectively and among 13 persons that response answer in don’t know

means they have no idea that health interfere in household chores, the

count (percentages) for male and female were 7(53.8%) and 6(46.2%)

respective. Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 37(37.0%)

persons that agree that diabetes affected social life, 43(43.0%) persons

that not agree that diabetes affected social life and 20(20.0%) persons

that response answer in don’t know means they have no idea that

diabetes affected social life. Among 37 that agree that diabetes

affected social life, the count (percentages) for male and female were

6(16.2%) and 31(83.8%) respectively and among 43 persons that not agree

that diabetes affected social life, the count (percentages) for males

and females were 26(60.5%) and 17(39.5%) respectively and among 20

persons that response answer in don’t know means they have no idea that

health diabetes affected social life, the count (percentages) for male

and female were 7(35.0%) and 13(65.0%) respectively.

Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 0(0.0%) persons that

are taking alcohol daily and 2(2.0%) persons that are taking alcohol

weekly and 5(5.0%) persons that are taking alcohol monthly and 93(93.0%)

persons are taking no alcohol. Among 0 that are taking alcohol daily,

the count (percentages) for male and female were 0(0.0%) and 0(0.0%)

respectively and among 2 persons that are taking alcohol weekly, the

count (percentages) for males and females were 2(100%) and 0(0.0%)

respectively and among 5 persons that are taking alcohol monthly, the

count (percentages) for male and female were 4(80.0) and 1(20.0) and 93

persons that are not taking alcohol, the count (percentages) for male

and female were 33(35.5) and 60(64.5) respectively. Figure 3 shows that

of out of 1000 respondents, 75(75.0%) persons that are living in non-

industrial area and 5(5.0%) persons that are living near the tyre

industry and 3(3.0%) persons that are living near the textile industry

and 5(5.0%) persons that are living near the steel mill and 12(12.0%)

persons are living near the other industries. Among 75 that are living

in non- industrial area, the count (percentages) for male and female

were 29(38.7%) and 46(61.3%) respectively and among 5 persons that are

living near the tyre industry, the count (percentages) for males and

females were 3(60.0%) and 2(40.0%) respectively and among 3 persons that

are living near the textile industry, the count (percentages) for male

and female were 2(66.7%) and 1(33.3%) and 5 persons that are living near

the steel mill, the count (percentages) for male and female were

1(20.0) and 4(80.0%) respectively and among 12 persons are living near

the other industries, the count (percentages) for male and female were

4(33.3) and 8(66.7%) respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000

respondents, 27(27.0%) persons that their area sanitary system is very

good and 45(45.0%) persons that their area sanitary system is good and

17(17.0%) persons that there area sanitary system is bad and 11(11.0%)

persons that their area sanitary system is very bad. Among persons that

their area sanitary system is very good, the count (percentages) for

male and female were 4(14.8%) and 23(85.2%) respectively and among 45

persons that their area sanitary system is good, the count (percentages)

for males and females were 27(60.0%) and 18(40.0%) respectively and

among persons that there area sanitary system is bad, the count

(percentages) for male and female were 7(41.2%) and 10(58.8%) and 11

persons that their area sanitary system is very bad, the count

(percentages) for male and female were 1(9.1) and 10(90.9%)

respectively. Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 60(60.0%)

persons that taking pills in medicine, 20(20.0%) persons that are taking

insulin in medicine and 20(20.0%) persons that taking combination of

pills and insulin in medicine. Among 60 persons that taking pills in

medicine, the count (percentages) for male and female were 24(41.4%) and

34(58.6%) respectively and among 20 persons that are taking insulin in

medicine, the count (percentages) for males and females were 24(40.0%)

and 36(60.0%) respectively and among 20 persons that taking combination

of pills and insulin in medicine, the count (percentages) for male and

female were 5(25.0%) and 15(75.0%) respectively.

Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 77(77.0%) persons

that taking medicine regularly, 17(17.0%) persons that are not taking

medicine and 6(6.0%) persons that miss sometime medicine. Among 77

persons that taking medicine regularly, the count (percentages) for male

and female were 25(32.5%) and 52(67.5%) respectively and among 17 %)

persons that are not taking medicine, the count (percentages) for males

and females were 10(58.8%) and 7(41.2%) respectively and among 6 persons

that miss sometime medicine, the count (percentages) for male and

female were 4(66.7%) and 2(33.3%) respectively. Figure 3 shows that of

out of 1000 respondents, 56(56.0%) persons that use of vitamins or

supplements, 43(43.0%) persons that are not use of vitamins or

supplements and 1(1.0%) persons that sometime use of vitamins or

supplements. Among 56 that use of vitamins or supplements, the count

(percentages) for male and female were 20(35.7%) and 36(64.3%)

respectively and 43 persons that are not use of vitamins or supplements,

the count (percentages) for males and females were 18(41.9%) and

25(58.1%) respectively among 1 persons that sometime use of vitamins or

supplements, the count (percentages) for males and females were

1(100.0%) and 0(0.0%) respectively . Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000

respondents, 5(5.0%) persons that meet their doctor weekly, 70(70.0%)

persons that meet their doctor monthly and 25(25.0%) persons that meet

their doctor yearly. Among 5 that persons that meet their doctor weekly,

the count (percentages) for male and female were 2(40.0%) and 3(60.0%)

respectively and 70 persons that meet their doctor monthly, the count

(percentages) for males and females were 28(40.0%) and 42(60.0%)

respectively among persons that meet their doctor yearly, the count

(percentages) for males and females were 9(36.0%) and 16(64.0%)

respectively . Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 86(86.0%)

persons that discuss problem in detail with doctor, 6(6.0%) persons

that are not discuss problem in detail with doctor and 8(8.0%) persons

that answer is don’t know means they don’t want to share that discuss in

detail with doctor or not. Among 86 persons that discuss problem in

detail with doctor, the count (percentages) for male and female were

34(39.5%) and 52(60.5%) respectively and among 6%) persons that are not

discuss problem in detail with doctor, the count (percentages) for males

and females were 2(33.3%) and 4(66.7%) respectively and among 8 persons

that answer is don’t know means they don’t want to share that discuss

in detail with doctor or not, the count (percentages) for male and

female were 3(37.5%) and 5(62.5%) respectively.

Figure 3 shows that of out of 1000 respondents, 78(78.0%) persons

that satisfied with their treatment, 12(12.0%) persons that are not

satisfied with their treatment and 10(10.0%) persons that response is

don’t know means they don’t want to share that are satisfied or not.

Among 78 persons that satisfied with their treatment, the count

(percentages) for male and female were 28(35.9%) and 50(64.1%)

respectively and among 12 persons that are not satisfied with their

treatment, the count (percentages) for males and females were 6(50.0%)

and 6(50.0%) respectively and among 10 persons that response is don’t

know means they don’t want to share that are satisfied or not, the count

(percentages) for male and female were 5(50.0%) and 5(50.0%)

respectively

Descriptive Analysis

In this section the frequency and percentages of the

demographic, different variable of diabetes will be discussed with

respect to diabetes gender. We will discuss here the frequency and

percentages of demographic variables There are 1000 subjects. The

debate of the results will base on the frequency, percentages.

Discussion

There were 39 males and 61 female’s people in sample of 1000.

Percentage of male persons=39.0%, Percentage of female persons=61.0%.

Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of marital status in

single and married group was 25(25.0%) and 75(75.0%) respectively. Out

of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of family members in 1-5,

6-10, 11-15 and 16-20 group was 37(37.0%),47(47.0%),12(12.0%) and

4(4.0%). Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of other

diabetic patient in family in 1-2, 3-4, 5-6 and No group was 34(34.0%),

8(8.0%), 3(3.0%) and 55(55.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the

number(percentage) of Persons address in towns, local areas and out of

Lahore group was 54(54.0%), 35(35.0%) and 11(11.0%) respectively. Out of

1000 respondents the number(percentage) of persons that following any

exercise in yes and no group was 80(80.0%) and 20(20.0%) respectively.

Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that have skin

problem after diabetes in yes, no and don’t know group was 17(17.0%),

79(79.0%) and 4(4.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the

number(percentage) of Persons that have wound healing problem after

diabetes in yes, no and don’t know group was 36(36.0%), 56(56.0%) and

8(8.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of

Persons that have kidney problem after diabetes in yes, no and don’t

know group was 18(18.0%), 74(74.0%) and 8(8.0%) respectively. Out of

1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that have vision

problem after diabetes in yes, no and don’t know group was 66(66.0%),

29(29.0%) and 5(5.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the

number(percentage) of Persons have weight loss after diabetes in yes, no

and don’t know group was 47(47.0%), 39(39.0%) and 14(14.0%)

respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons

have weight gain after diabetes in yes, no and don’t know group was

20(20.0%), 66(66.0%) and 16(16.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents

the number(percentage) of Persons that hoteling in yes and no group was

37(37.0%), 63(63.0%) respectively.

Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that taking

kind of meal in Wheat, Rice and Fiber group was 84(84.0%), 13(13.0%)

and 3(3.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage)

of Persons that number of taken meal in a day in 1, 2, 3 and 4 group

were 1(1.0%) 19(19.0%), 71(71.0%) and 9(9.0%) respectively. Out of 1000

respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that are frequently

hoteling in Never, Sometimes, Normally and Frequently group was

64(64.0%), 23(23.0%) ,8(8.0%) and 5(5.0%) respectively. Out of 1000

respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that regularly test their

blood sugar level in yes, no and don’t know group was 51(51.0%),

42(42.0%) and 7(7.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the

number(percentage) of Persons that check their sugar in a day in once a

day, twice a day, Weekly and Monthly group was 8(8.08%), 20(20.0%),

46(46.0) and 26(26.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the

number(percentage) of Persons that fluctuate their sugar in never,

sometimes and every time group was 28(28.0%), 45(45.0%), 27(27.0)

respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons

living in industrial area Yes and NO group was 25(25.0%) and 75(75.0%)

respectively. Out of 100 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons

living near the which factory in None, Tyre industry, Textile industry,

Steel and Others group was 75(75.0%), 5(5.0%), 3(3.0%), 5(5.0%),

12(12.0%) respectively .Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage)

of Persons living area in rural area and urban area group was 23(23.0%)

and 77(77.0%) respectively.

Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons satisfied

their sanitary system in very good, good, bad and very bad group was

27(27.0%), 45(45.0%), 17(17.0%) and 11(11.0%) respectively .Out of 1000

respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that use which type of

water in tap and filter group was 42(42.0%), 58(58.0%) respectively. Out

of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that taking kind

of medicine pills, insulin and combination group was 60(60.0%),

20(20.0%) and 20(20.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the

number(percentage) of Persons that regularly take medicine in yes, no

and miss sometimes group was 77(77.0%), 17(17.0%) and 6(6.0%)

respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons

that are used vitamin or supplements in yes, no and sometime group was

56(56.0%), 43(43.0%) and 1(1.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents

the number(percentage) of Persons that meet their doctor in Weekly,

Monthly, and yearly group was 5(5.0%), 70(70.0%) and 25(25.0%)

respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons

take alcohol in yes and no group was 6(6.0%) and 94(94.0%). Out of 1000

respondents the number(percentage) of Persons smoking in yes and no

group was 22(22.0%) and 78(78.0%). Out of 1000 respondents the

number(percentage) of Persons that are going for daily walk in yes, no

and do not know group was 79(79.0%), 21(21.0%) respectively.

Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that think

the exercise is necessary for diabetic patients in yes, no and do not

know group was 80(80.0%), 17(17.0%) and 3(3.0%) respectively. Out of

1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that think routine

walk is helpful for diabetic patients in yes, no and do not know group

was 88(88.0%), 9(9.0%) and 3(3.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents

the number(percentage) of Persons follow doctor regarding exercise in

yes, no and don’t know group was 67(67.0%), 32(32.0%) and 1(1.0%)

respectively Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons

that take proper fruit in yes, no and sometime group was 41(41.0%),

20(20.0%) and 39(39.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the

number(percentage) of Persons that take milk regularly in yes, no, and

sometime group was 48(48.0%), 43(43.0%) and 34(34.0%) respectively. Out

of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that skip their

meal in yes, no and sometime group was 37(37.0%), 34(34.0%) and

29(29.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage)

of Persons that take care of their diet in yes, no and don’t know group

was 71(71.0%), 20(20.0%) and 9(9.0%) respectively. Out of 1000

respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that affected their daily

life from diabetes in yes, no and don’t know group was 47(47.0%),

35(35.0%) and 18(18.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the

number(percentage) of Persons that their household chores affected form

health in yes, no and don’t know group was 55(55.0%), 32(32.0%) and

13(13.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage)

of Persons that spend the day for exercise in morning, afternoon,

evening and no group was 42(42.0%), 4(4.0%).31(31.0) and 23(23.0%)

respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons

that walking time in morning, afternoon, evening and no group was

52(52.0%), 4(4.0%). 23(23.0) and 21(21.0%) respectively. Out of 1000

respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that record their sugar

levels in yes, no and do not know group was 52(52.0%), 32(32.0%) and

16(16.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage)

of persons that their sugar remains normal in yes, no and don’t know

group was 43(43.0%), 39(39.0%) and 18(18.0%) respectively. Out of 1000

respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that think diabetes become

hindrance in their daily walk activities in yes, no and do not know

group was 52(52.0%), 31(31.0%) and 17(17.0%) respectively. Out of 1000

respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that their health

interferes in their hobbies and recreational activities in yes, no and

don’t know group was 52(52.0%), 32(32.0%) and 18(18.0%) respectively.

Out of 1000 respondents the number(percentage) of Persons that their

social life affected from diabetes in yes, no and don’t know group was

47(47.0%), 35(35.0%) and 18(18.0%) respectively. Out of 1000 respondents

the number(percentage) of Persons that are frequently use alcohol in

daily, weekly, monthly and none group was 0(0.0%), 2(2.0%),5(5.0%) and

93(93.0%) respectively. Out of 100 0respondents the number(percentage)

of Persons that discuss their problems in detail with the doctor in yes,

no and don’t know group was 86(86.0%), 6(6.0%) and 8(8.0%)

respectively.

Read More About Lupine Publishers Journal of Current Trends on Biostatistics & Biometrics Please Click on the Below Link:

https://lupine-publishers-biostatistics.blogspot.com/