Lupine Publishers | Journal of Clinical & Community Medicine

Abstract

This essay suggests three ways in which compulsory vaccination can be taken forward should the UK Government decide to do so. It addresses the question of; how can we ensure that public concerns about compulsory vaccination are considered if compulsory vaccination is to be introduced by the UK Government? Arguments for and against compulsory vaccination from the literature ate provided. However, the interest here is not whether compulsory vaccination should be adopted or not but how best to take this forward should the UK Government decide to take this forward.

Background

On the 29th of September 2019, the United Kingdom (UK) Government suggested that it was “looking very seriously” into the introduction of compulsory vaccination for school children [1]. This follows the recommendation of four London senior National Health Service (NHS) GP’s including Sir Sam Everington, Dr Mohini Parmar, Dr Andrew Parson and Dr Josephine Sauvage [1]. The UK Health Secretary, Matt Hancock, speaking at the Tory conference, said: “I’m very worried about falling rates of vaccinations, especially measles” ... “For measles, the falling vaccination rates are a serious problem, and it is unbelievable that Britain has lost its measles-free status.” [2]. Earlier this year, the UK lost it ‘measles eradicated’ status with the World Health Organisation (WHO) [3]. Worldwide, figures show a rise of 300% reported cases of measles in the first three months of 2018 when compared the same time period of the previous [4]. MMR vaccine rates in England has been in the decline since the last five years [5] and according to figures from the Childhood Vaccination Coverage Statistics England 2018-2019 – there was a decline from 91.2% of vaccinated children to 90.3% when data was compared with the previous year.

Compulsory vaccination has previously been introduced in other countries such as the United States and Australia [6]. The main argument is that compulsory vaccination protects other children who cannot be vaccinated for other medical reasons. Compulsory vaccination is neither new in the UK, for example, when compulsory smallpox vaccination was introduced for all children born after 1853 [7]. Childhood vaccination programmes have seen successful eradication of diseases such as smallpox in the UK and brought under control other diseases such polio, diphtheria, whooping cough, and meningitis, and they extend back to the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, vaccination remains voluntary in the UK, and as such, public communication, education and trust have been relied upon [8] as a means to maintain high uptake to ensure herd immunity [9].

Other concerns for health authorities, is the rise in unproven theories linking vaccines to diseases such as autism, multiple sclerosis and diabetics; and the rise of anti-vaccination movement on social media on the other hand. For example, Wakefield et al. [10] published in ‘The Lancet’ described twelve children aged between three and ten, suffering from developmental regression and gastrointestinal problems. Andrew Wakefield in a press conference prior to this publication suggested a possible link between measle, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism. However, the study could not be replicated elsewhere. The Lancet paper was retracted and Andrew Wakefield was struck off the British medical register by the General Medical Council for serious professional misconduct in 2010 [11]. Nevertheless, this false hypothesis continues to shape the MMR vaccine debate especially with the rise of social media anti-vaccine movement. According to the UK Health Secretary, “If you don’t vaccinate your child and you can, then the person you are putting at risk is not only your own child, but it is also the child who can’t be vaccinated for medical reasons”. He called those who spread anti-vaccine messages as having “blood on their hands” asking social media platforms to do more to curb the ant—vaccination movement on social media [12].

Compulsory vaccination to a wide range of childhood diseases such as polio, measles, mumps, and rubella and pertussis have in the past met with fierce legal and legislative challenges justified by ideological, scientific, religious and political philosophies. Thus, it is expected that moves to make the vaccine compulsory in the UK would generate a new round of emotionally charged debates. In response to Government suggestion of the possibility of introducing compulsory vaccination, the British Society for Immunology chief executive Dr Doug Brown said: “to make this compulsory in the UK, there are concerns that it could increase current health inequities and alienate parents with questions on vaccination” [13]. Dr Brown noted that more can still be done in terms of information campaigns and the delivery of local immunisation in communities. The Royal Society for Public Health noted that “compulsory vaccination should be a last resort.

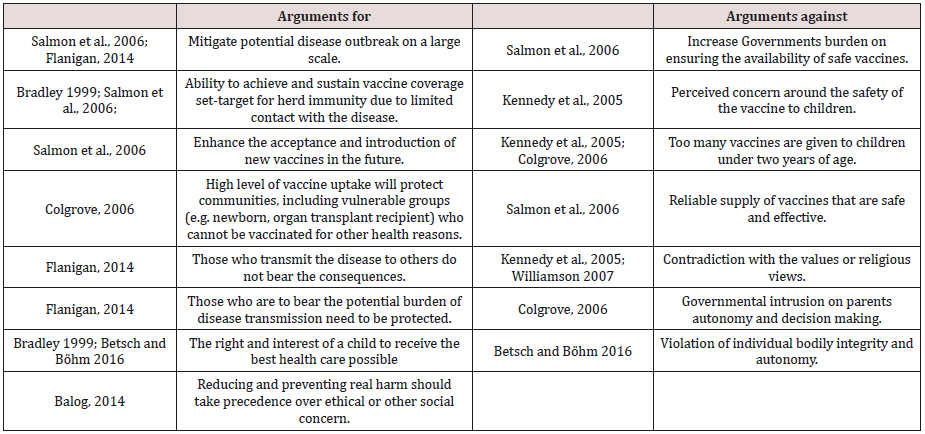

Table 1 below set out arguments for and against compulsory vaccination. This review is not meant to be exhaustive, but rather, it is a selection of literature that illustrates some of the core arguments for or against compulsory vaccination debate. The focus of this opinion essay is not whether compulsory vaccination should be adopted or not but how best to take this forward should the UK Government decides to take this forward.

Compulsory Vaccination and Public Engagement

An interesting question therefore is; how can we ensure that public concerns about compulsory vaccination are considered if compulsory vaccination is to be introduced by the UK Government? Research on risk communication has shown that simply understanding the rationale and the science behind such policy intervention does not necessarily translate to trust and acceptance of public health policy interventions. Often times, the public would have concerns and questions which they would want to be answered even if the science is settled, see for example. This essay, therefore, suggests three ways in which compulsory vaccination can be taken forward should the UK Government decide to do so.

Firstly, debates about new public health policy interventions are never just about science and evidence. This is especially the case where science conflict with group beliefs, values or religious convictions as proven by psychometric and social theories of risk. People will interpret public health policy interventions in a range of different contexts including their situational context. Therefore, the Government must be willing to understand the variety of political, ethical, scientific, cultural, religious and ideological context that exist and how this would affect the interpretation that will be brought to bear on the compulsory vaccination intervention by the Government. This way, the Government could set out exceptions and boundaries, in a way that would effectively ease any backlash or resistance that could arise if the policy is implemented.

Secondly, there is a need for Government to understand what people’s hopes and concerns about compulsory vaccination are. This is important as the public, who are adopters of policy intervention, should have a say in how, where and who is affected by mandatory vaccination. Important questions that could potentially arise here are - would the public value their autonomy than been compelled? This sits within the libertarian or nannystate arguments where some critic would see this as a step too far into family matters. Other questions are: who decides who is compelled or not and in what conditions? What evidence decides this parameter? Can parents delay child vaccination should they have concerns? It would also be good for the Government to set out how public concern raised will be considered and addressed. This will ease the burden and pressure around public acceptability of any compulsory vaccination policies.

An example of a recent public engagement on public health interventions can be seen in the case of the electronic cigarette (EC) debate; even if the public engagement tended to be limited to the acceptability debate and not necessarily the technical debate [14]. The EC debate was triggered by the sharp rise in the use of EC in the UK, and a call by the WHO in 2008 who raised concerns that ECs were being marketed as a safer alternative to tobacco cigarettes despite a lack of, or insufficient, scientific understanding of the safety and efficacy of ECs at the time (WHO, 2008). EC is currently being regulated under the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) following public consultation carried out in 2010 on whether to bring nicotine-containing products (NCPs), including ECs, within the medicines licensing regime. This regulation came into effect in May of 2016 and according to the directive, ECs containing up to 20mg/ml of nicotine will be regulated by the TPD. However, whether this regulation will change in light of recent EC health concern (vaping illness) in the US [2] and following Britain’s exit from the European Union, remains unknown as at the time of writing this article.

Finally, like much other public engagement, the Government will need to be clear and honest if, why and when they want to engage with the public if there are to take compulsory vaccination forward. Risk communication research has shown that public engagement can open up areas of agreement and conflict that can have implications for trust and risk acceptability. However, they must be used in ways that challenge, rather than reinforce powerful incumbent societal structures [15,16]. If compulsory vaccination is to be introduced, then public engagement will be beneficial to empower and give voice to concerned public groups. Then, the objective of this engagement should guide when and how the public debate should take place. In the case of the electronic cigarette debate, for example, the MHRA-led public consultation was influential in shaping the questions and arguments that were brought to bear on the vaping debate [17-24].

Read More About Lupine Publishers Clinical and Community Medicine Please Click on Below Link:

https://journalofclinicalcommunitymedicine.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.