Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry

Abstract

Beckwith – Wiedemann syndrome is congenital, genetic and epigenetic pathologies with low prevalence and diverse clinical presentations. It is characterized by triad of omphalocele, macroglossia and gigantism. This syndrome has been widely studied with a current emphasis on improvement of prenatal diagnostic techniques and a multidisciplinary approach towards treatment. We report a case of BWS from Saudi Arabia, with unique presentations and misleading history which delayed diagnosis, due to cultural and religion constraints.

Keywords:Congenital; Epigenetic; Genetic; Prenatal

Introduction

Genetic and epigenetic changes or a human genomic imprinting disorder is characterized by phenotypic variability which might shows its occurrence either as sporadic or inherited. The pathology presents wide range of effect on psychological and social wellbeing of patients and families. One such congenital, multigenic, multisystem human genomic imprinting disorder with complex molecular etiology and variable complex phenotype is Beckwith – Wiedemann Syndrome (BWS). Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome is most common overgrowth syndrome described by Beckwith in 1963 and Wiedemann in 1964 with similar findings. It is rare congenital deformity with low prevalence but at same time have high prevalence within genetic abnormalities of overgrowth [1]. The presentation of triad features of omphalocele (exomphalos), macroglossia and gigantism was described earlier as EMG syndrome which now is referred as Beckwith – Widemann Syndrome. The incidence of BWS reported is approximately 1:13700 births and the major cause is thought till date is genetic and epigenetic defects within the chromosome 11p15.5 regions [2].

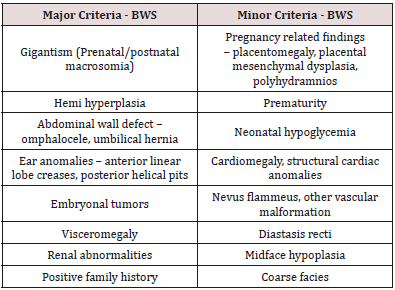

BWS presents wide array of clinical manifestations such as congenital abdominal wall defects as hernia (exomphalos), gigantism, macroglossia, nevus flammeus, ear pits/hearing loss, midface hypoplasia, cardiac anomalies, hemihypertrophy, genitourinary anomalies and musculoskeletal abnormalities. To standardize the diagnostic criteria various attempts have been made to classify the major and minor criteria. Elliot et al described the diagnosis of BWS with the presence of either three major features (abdominal wall defect, macroglossia, gigantism) or two major and three minor features (ear pits, nevus flammeus, hemi hyperplasia, nephromegaly, neonatal hypoglycemia) [3]. In spite of diverse clinical presentations of BWS, most of the cases do not show characteristic features at birth but develop later in life. Also, children with BWS have significantly increased risk of cancer during early childhood which need strict follow up and monitoring. Here, we present a case of BWS with unique dental and medical presentation and its differential diagnosis with literature review.

Case Report

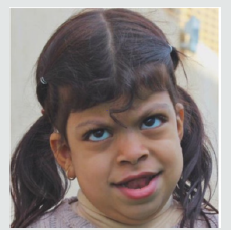

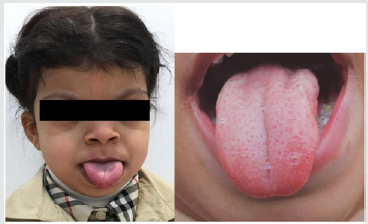

A 5-year-old female patient, accompanied by her mother, presented to the dental unit with complaint of decay tooth in upper front region of mouth. Extra oral examination revealed dysmorphic features, coarse facies and developmental problems (Figure 1). Intra oral examination of hard tissue showed high arched palate, decayed teeth in relation to 51, 52, 55, 61, 62, 74, 75, 84,85. Oral soft tissue examination revealed macroglossia, enlargement of fungiform papillae and mild loss of filiform papillae (Figure 2). Speech and feeding difficulty were noticed due to macroglossia. History revealed she is the youngest 7th child born out of consanguineous marriage in 30th week by cesarian section. She has a chronic history of constipation for 9 months of age. She passes hard stool once in every 8 to 10 days, by spending long time in washroom. It is associated with decrease in appetite and abdominal pain. She was given Movicol (half the adult dose) twice a day for constipation without any medical prescription. She was also tried with lactulose, glycerin suppository and mineral oil. Under medical supervision fleet enema and contrast enema were performed to relieve constipation and to rule out Hirschsprung disease.

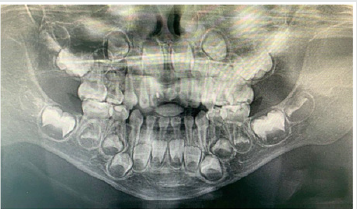

Other medical findings noticed omphalocele, ear pits, large child at 90th centiles, large rounded eyes with hypertelorism, abdominal soft lax, enlargement of kidney, distention of left renal pelvis with significantly distended urinary bladder, abnormal anatomy of the colon located in left abdomen and partial colonic non – rotation with no evidence of obstruction (Figure 3). Based on the clinical and past medical history a diagnosis of Beckwith – Wiedemann Syndrome (BWS) was made. Series of laboratory investigation were reviewed which presented negative urine examination, alpha – fetoprotein, karyotype, microarray and methylation analysis for BMS. Patient was advised for gene analysis and targeting testing for parents. The gene analysis of CDKN1C gene showed heterozygous alteration consistent with BWS but targeting gene tests were refused by parents. Panoramic radiograph was advised considering the patient chief complaint, which revealed multiple developing permanent tooth buds, protrusion of anterior teeth, open bite and increase in mandibular dimension (Figure 4). Under preventive measures the patient was treated for the decayed teeth and is under follow up from past 6 months.

Figure 4: Panaromic radiograph showing multiple developing permanent tooth buds, open bite and increased mandibular dimension.

Discussion

Diagnostic criteria for BWS is still a matter of research due to its varied clinical presentations and overlapping features with other various conditions. The presence of major and minor findings is generally helpful in establishing the clinical diagnosis (Table 1). The oral findings as mentioned in the literature and observed in our case has been tabulated in Table 2 [4,5]. The incidence of BWS is difficult to assess in Saudi Arabia, as most of the cases goes undiagnosed and unnoticed. Also attributed to its diverse clinical presentation and difficulty in diagnosing. In the present case, features of macroglossia, macrosomia, omphalocele, abdominal wall defect (treated immediately after birth and surgical scar observed clinically), Renal involvement, ear crease, high arched palate, open bite and increased mandibular dimension, leads to the diagnosis of BWS. Various molecular mechanisms and alterations have been involved in BWS such as abnormal methylation of H19DMR, loss of imprinting of IGF2, chromosomal rearrangements, loss of imprinting of LIT1, uniparental disomy of 11p15 and CDKN1C mutations [2]. The full gene analysis of CDKN1C gene profile were suggestive of BWS in our case and the alteration is thought to be located in the allele inherited from the mother. Parental testing was advised which was refused by the parents. There are various endocrine and overgrowth syndromes that was considered in the differential diagnosis. These included Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome (mutation in X-linked gene, GPC3), Perlman syndrome (Increased risk of neonatal mortality), Costello syndrome (missense mutation in HRAS), Sotos syndrome (Mutation in NSD1) and Mucopolysaccharidosis type IV (lysosomal storage disorder) [6]. Oral findings like macroglossia of BWS needs differentiation from other lesions like lymphangioma, idiopathic muscular hypertrophy, hemangioma, rabdomyomas, amyloidosis, cretinism and acromegaly.

The overall risk of BWS for tumor development/malignancies is estimated to range from 4 – 21%. The tumors reported with BWS are mainly embryonal tumors such as Wilms tumor, hepatoblastoma, rabdomyosarcoma, adrenocortical carcinoma and neuroblastoma [7]. The prenatal diagnosis with current technology is increasing representing an important tool to determine some features of BWS before birth. In our case, parents were highly orthodox and refuse to share the detailed prenatal and ultrasonic reports. Few misguided information’s were given by mother which was later clarified with the reports from the subsequent medical hospitals. Patient’s parents were advised for periodic follow up with genetic counselling and the possibility of surgical interventions in the medical units, but they refused to follow and changed the hospitals every time. Hence, an effort was put forward to retrieve the information’s related to the patient while giving her the primary treatment for which she reported to our dental unit. This suggest the need of awareness required in the country like Saudi Arabia, where most of the cases goes unreported/unnoticed or parent’ consent not given or the cultural and religion barriers that prevent reporting such cases. Though the patient was treated with dental fillings, the follow up of the patients is been restricted by the family members.

Conclusion

Beckwith – Wiedemann Syndrome patients usually grow and do well despite being at increased risk of childhood cancer. Hence, strict follow up, awareness of parents and cancer screening is mandatory. Families, physicians and dentists should determine screening schedule including abdominal ultrasound in every three months, blood test to measure alpha-fetoprotein in every six weeks, dental check-up in every six months and other symptomatic treatment schedule as and when required.

Read More Lupine Publishers

Pediatric Dentistry Journal Articles:

https://lupine-publishers-pediatric-dentistry.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.