Lupine Publishers | Journal of Anthropological and Archaeological Sciences

Abstract

The amount of surviving inscriptions from the Ottoman Times in Greece is astonished. This paper is the first ever study announces these inscriptions throughout Greece in a quantitative approach. Through statistical methods, this research surveys the building inscriptions, proper to each region or in Greece as a whole. This article surveyed 684 inscriptions belong to 343 Ottoman buildings all-over Greece. Considering the language and the content of these 684 inscriptions, they comprise 1788 different texts. It shows with the help of two tables along with their charts with type, building function and region indexes the criteria of classification of these inscriptions considering the most common approaches comprising language, function, content, patron, stylistic features and region. It is also analyzing the surviving inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece considering these criteria with statistic evidences. The paper concludes with a suggested methodology in cataloguing the corpus of the inscriptions of Ottoman buildings in Greece.

Keywords: Inscription; Ottoman; Balkan; Greece; Epigraphy; Corpus

Introduction

The Ottoman existence in the present-day Greece began in 1361 AD, when the Ottomans took possession of Didymoteichon. The Ottomans ruled the present-day Greek territories for periods almost ranging between three and five centuries as the case in Thrace, Macedonia and Thessaly. During that period thousands of buildings were constructed under the Ottomans’ patronage throughout Greece. Though a large number of Ottoman architectural heritage in Greece has been demolished, due to different factors, still the extant Ottoman buildings in Greece represent, as a whole, one of the biggest well-preserved and varied collection of Ottoman architecture in the Balkans [1].

One of the most characteristics of Islamic art and architecture is the extensive use of lettering. The Ottoman art and architecture were no exception. Though, a large number of Ottoman inscriptions in Greece were lost, still the preserved ones represent, as a whole, one of the biggest well-preserved and varied collection of Ottoman inscriptions in the Balkans.

Inscriptions related to Ottoman presence in Greece could be classified into three main categories:

a) Building inscriptions.

b) Tombstones

c) Artifacts and numismatics inscriptions.

The latter group is very interesting and did not gain the deserved attention of the scholars yet. It basically presented via the objects including jewellery, swords, furniture, tools and coins that are found either exhibited or stored in the museums throughout Greece with special reference to the Numismatics and Benaki Museums at Athens, Museum at Arslan Pasha Mosque (Figure 1) of Ioannina, the Historical Museum (Figure 2) at Iraklion (Crete) and the Archaeological Museum (Figure 3) at Drama (Northern Greece).

Ottoman tombstones in Greece forming one of the most plenteous collections in the Balkans. Many historic cemeteries of hundreds tombstones are found in Greece especially in Komotini, Xanthi, Crete, Rhodes, Kos and Chios. Some collections are well documented as the case of Komotini [2], Rethymno (Crete) [3], but the others are still unknown. Some groups of tombstones are gathered in a dangerous way which may destroy them as in Iraklion (Figure 4).

Figure 1: A group of Ottoman swords exhibited in the museum inside the Arslan Pasha Mosque of Ioannina (@ Ahmed Ameen 2008).

This research compiles only the inscriptions of the first category i.e. building inscriptions. This study counted 684 inscriptions related to 343 buildings throughout Greece. Considering the language and the content of these 684 inscriptions, they comprise 1788 different texts. For example, one inscription may include two or three different texts: a qur’anic quotation, and/or an invocation, and foundation text. Also, some inscriptions are bilingual or trilingual [4].

This paper provides a statistic inventory of the extant inscriptions of the ottoman buildings in Greece. Moreover, notes some considerations on this epigraphic material discussing their importance, numbers, categories and the different supposed ways of classification.

Classification of Inscriptions

Generally, Islamic inscriptions are classified according to multiple inputs, including language, historical period, calligraphy features, raw material where the inscription executed on, methods of execution, framework or general design of inscriptions, content, etc. The most common approaches of classification are language, function, content, patron, stylistic features and region.

Language

The language(s) of the inscriptions on Ottoman architecture in Greece came in Arabic, Ottoman Turkish (in Arabic alphabet), Modern Turkish (in Latin), Persian, and Greek.

Most of the inscriptions came, of course, in Arabic and Ottoman Turkish. Three surviving inscriptions in Persian, as far as I know, one is preserved in the Historical Museum of Iraklion, Crete, one of the türbe of Sheikh Hortaci (St. George Church, Rotunda) at Thessaloniki, while the third is inside the Arslan Pasha Mosque at Ioannina (Figure 5). These Persian texts refer to the presence of Sufi orders within Ottoman communities in Greece in particular, and in the Balkans as a whole.

Figure 5: The Arabic-Persian inscription of the central medallion of the interior of the dome of Arslan Pasha Mosque in oannina (First publishing, @ Ahmed Ameen 2008).

Some inscriptions are also written in Greek, French and Italian, as well as in Modern Turkish; characterizing the last stage of Ottoman presence in Greece, and continued somewhat after the end of the ottoman rule of Greece, especially in Thrace.

Arabic was the main and official language of Ottoman foundation and historic inscriptions in Greece and the Balkans during the early ottoman period, which extended from the beginning until the early 16th century [5, 6]. The language of the inscriptions became significantly Ottoman Turkish, especially since the mid-16th century, by the end of this century it became the official language of the inscriptions as well as all aspects of culture and art in the Ottoman Empire. Numbers of the existing foundation inscriptions, classified in terms of language and date, clearly reflect this hypothesis.

Complete foundation, restoration or renovation inscription consists of five main elements [7]:

a) The basmala or qur’anic quotation or invocation to God.

b) A verb representing what was done.

c) The object of the work.

d) The patron’s name (and sometimes his titles).

e) The date of construction/restoration.

If an inscription bears the date of the foundation or restoration but missed one or more of these elements, I will name it as a short foundation inscription.

There are 367 foundation/restoration inscriptions, either full or short, of the Ottoman buildings in Greece comprising 54 in Arabic, 210 in Ottoman Turkish, 60 inscriptions in Greek, 4 inscriptions in Byzantine, 3 inscriptions in modern Turkish, two inscriptions in French, 9 inscriptions representing dates recorded in numbers only, and 25 inscriptions-some represent foundation inscriptions, others are informal personal inscriptions-written in more than one language, will be studied in detail in the second part of this research, bilingual and trilingual inscriptions.

This group of Arabic foundation inscriptions (54) composes a considerable number, especially if compared to any other country in the Balkans. The content of these inscriptions provides a wealth of data concerning their contemporaneous Ottoman community.

Worth mentioning, that 50 inscriptions from the 60 Greek ones belong to fountains ‘çeşme’ were found on the island of Lesbos ‘Mytilene’ [8]. The rest 10 Greek inscriptions belong to fountains and residential buildings distributed in the towns and villages of Komotini, Xanthi, Rhodes and Crete. Though, most of the patrons of the structures that bear Greek inscriptions were Greeks and not Ottomans, but these buildings were built during the Ottoman rule influenced by the Ottoman culture; characterizing late Ottoman period in Greece. The biggest bulk of the extant non-religious inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece is surely came in Ottoman Turkish language.

Function

Studying the building inscriptions in terms of function is a common approach. The inscriptions of each category of buildings are often alike in their content. Regarding the inscriptions of Ottoman buildings in Greece, as far as concerned, are divided according to function (Table 1, Chart 1) as follows: 117 inscriptions belong to Mosques, 118 to water works (109 fountains ‘çeşme’ and ‘şâdırvân’, 2 water reservoir, 3 springs, 2 baths ‘hammams’, 1 aqueduct and 1 bridge ‘Köprü’), 20 belong to educational buildings (17 to mektep, medrese, idâdî and rüşdiye, and 3 to libraries ‘kütüphane’), 17 inscriptions belong to tekke, imaret, and zawiya, 15 inscriptions belong to fortifications, 14 inscriptions belong to mausoleums ‘türbes’, 17 inscriptions belong to houses, 7 inscriptions belong to clock-towers ‘saat kulesi’, 4 inscriptions belong to commercial building (2 khans and 2 shops), 2 inscriptions belong to courts, in addition to one inscription belongs to a prison, and one to a customs building ‘gümrük’.

Studying the inscriptions in this regard helps to detect the change in the building function and the different names of the building of almost same function over centuries. This approach is useful especially if the research covering a long period as our case study. The various names of the educational institutions on the ottoman inscriptions comprising: mektep, medrese, idâdî, rüşdiye, dârülfünun, etc. show a good example.

Generally, text follows function; thus the content of the inscriptions of the buildings belong to the same function is somewhat alike. As the case of the educational buildings, the texts usually concentrated on the highest value of learning and teaching in Islam, the prestigious position of the professors ‘müderris’ and the texts that encourage the students to learn.

Content

The epigraphic content is the most important data to study the history of any building, and its historic context. Analyzing the content of the inscriptions is a most popular approach in epigraphic studies. The content of the epigraphic material of the buildings could be studied in many ways. Considering the extant inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece, there are six different approaches available to present the content of those inscriptions as follows:

1) Foundation/restoration (or dedicatory) inscriptions

2) Religious inscriptions

a. Qur’anic inscriptions

b. Non-Qur’anic inscriptions

3) Endowment text

4) Funerary text

5) Signatures

6) Graffiti

The above groups are not exclusive but often overlap, as the case of a foundation inscription which may also contain a qur’anic quotation and/or the signature of a craftsman.

All previous studies almost tackled only the foundation/ restoration inscriptions, following the traditional western approach that focuses on historic inscriptions underscores the history of the building and its patron(s). This approach slights religious inscriptions, though the latter form the biggest group of inscriptions, 350, existed in Greece. These 350 religious inscriptions can shed light on the meaning and function of the building; even most religious inscriptions are repeated in stereotyped formulas.

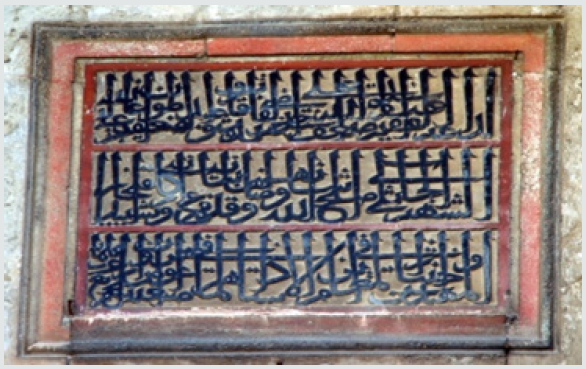

There is only one example belong to each category of endowment and funerary inscriptions. The endowment inscription is placed on the wall of Mahmoud Ağa Mosque (Figure 6) which also known as ‘Yenice Mahalle Camii’, while the funerary one is found inside the mosque of Karaca Ahmed (Figure 7) which built in 1450 and renewed in 1950 in the village of Shaheen in Xanthi.

Figure 6: An endowment “Waqffiye” inscription of Mahmud Agha Mosque at Komotini (@ Ahmed Ameen 2008).

Signature inscriptions come in both cases:

a) as a single inscription as the case of the Yeni Mosque at Thessaloniki (Figure 8), of the Italian architect Vitaliano Poselli [4], and

b) included in a foundation inscription with two distinguished examples.

The first is the subordinate Arabic foundation inscription of Sultan Mehmed Çelebi Mosque at Didymoteicho, providing the name of the famous Turkish Architect Haci İwaz “ ʿawaḍ” (Figure 9) [5]. The second is the Greek inscription of the Sultan Abdülhamid II çeşme (1301/1884) in Kalami village at Chania, Crete. It provides the name of its Greek architect Georgaraki (Figure 10) [4].

Figure 7: A funerary inscription inside the mosque of Karaca Ahmed in the village of Shaheen in Xanthi (@ Ahmed Ameen 2008).

Figure 8: A signature inscriptions of the architect of the Yeni Mosque at Thessaloniki (@ Ahmed Ameen 2009).

Figure 9: the second Arabic foundation inscription of Sultan Mehmed Çelebi Mosque at Didymoteicho (@ Ahmed Ameen 2009).

Figure 10: Both Ottoman and Greek inscriptions of the Sultan Abdülhamid II çeşme of the Kalami village at Chania (@ Ahmed Ameen 2016).

Graffiti inscriptions are incised handwritings on stone or marble that adorned many Ottoman buildings throughout Greece. They are represent the travellers’ writings and express one’s impressions and thoughts. Graffiti inscriptions come usually on the frames of the doors and windows of the buildings as the case of Fethiye Mosque at Athens, and Ishak Paşa Mosque at Thessaloniki and Ibrahim Pasha Mosque in Rhodes, and sometimes on the shafts of the colmuns of the portico as the case of Arslan Pasha Mosque at Ioannina and Sultan Süleyman Mosque in Rhodes.

Graffiti inscripions repesnet usually religious writings comprising qur’anic quotations, hadith or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, invocations, poems, and may also recorded the name and/or the nickname of the scriber and sometime scribed a date. Graffiti inscriptions sometime are very useful and in some cases it helps to date the structure on which they are found as the case of the Fethiye Mosque at Athens [9].

Patron(s) and Craftsman

One of the most specific approaches in studying inscriptions is the patron(s) either as a person, family, position or rank, sex; to whom such inscriptions are belong. Thus we found studies entitled the inscriptions of the Sultan(s), women, architect, calligrapher, etc.

The inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece, as far as concerned, represent various patrons including Ottoman sultans themselves (Bayezid I, Mehmed Çelebi, Murad II, Bayezid II, Süleyman the Magnificent, Mustafa III and Sultan Abdülhamid II), the high ranking class (Includes the Sultans’ relatives, the Grand Vezirs, Vezirs and commanders, such as Mehmed Bey Mosque at Serres, a foundation of son of Grand Vezir Ahmad Paşa and husband of Princess Selçuk Hatun, daughter of Sultan Bayazid II) [10]. Also there are some inscriptions provides the women as patrons of Ottoman architecture, and in some cases buildings were built by husbands dedicated to their wives as the case of many fountains.

The studied inscriptions present a shifting in the patronage of the construction of mosques and medreses replacing single funded patronage of the Sultans or grand commanders or officials or wealthy individuals with the Muslim community i.e. the Muslims of a district or a village as a patron of building mosques as in the Ierapetra Mosque [11] at Crete, and the Alankuyu Mosque and the Kir Mahalle Medrese at Komotini.

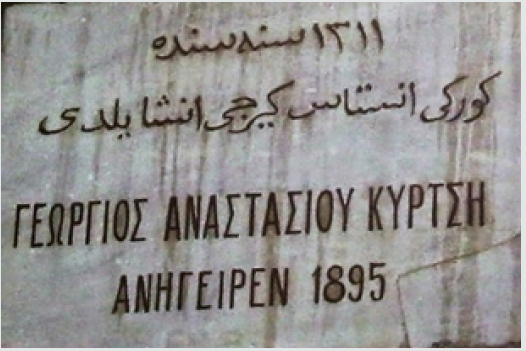

Noteworthy, that wealthy Christian Greeks has also participated in constructing secular welfare buildings in late ottoman period, as the case of the Clock-tower of Naousa ‘Ağustos’ which was built by industrialist George Anastasiou Kergi in 1895 as cited in its still extant bilingual inscription (Figure 11) [4].

Figure 11: The bilingual foundation inscription of the Clock-tower of Naousa (@ https://odosell.blogspot.com/2014/04/ blog-post_9961.html [Accessed on 25 June 2018]).

Stylistic Features

Figure 12: A Kufic inscription above the lateral niche eastern the main entrance of Sultan Mehmed Çelebi Mosque at Didymoteicho (@ Ahmed Ameen 2008).

Studying the inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece in terms of style tackles their visual characteristics. Thus, it deals with the placement, height, dimensions, material on which is executed, colors, the shape of inscription as a whole, the way that the inscription is divided in, the shape of the letters and methods of execution of the inscriptions. The inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece, as far as concerned, still in lack of such this study.

It is worth noting that each one of the aforementioned items of stylistic features may be used as a clue of dating other comparable undated inscriptions. The monumental inscriptions of Sultan Mehmed Çelebi Mosque at Didymoteicho represent a very interesting example of early Ottoman inscriptions. They are executed in thuluth and Kufic (Figure 12) scripts; characterizing the transitional stage of execution the monumental inscriptions in early Ottoman period. The majority of the inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece are executed in thuluth script (jali; Turkish celi).

Region

Studying Islamic inscriptions on a geographical basis, by country, region, island or city, is a typical approach. Since the geographically norm is the standard way of documenting of inscriptions; it is also adopted here in the suggested cataloguing method for the inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece.

Figure 13: A map shows the regional units of Greece (@ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geographic_regions_of_Greece [Accessed on 16 June 2019]) [12].

Administratively, there are thirteen regional units (prefectures or peripheries) form the present-day Greece (Figure 13), comprising:

1) Attica.

2) Central Greece.

3) Central Macedonia.

4) Crete.

5) Eastern Macedonia and Thrace.

6) Epirus.

7) Ionian Islands.

8) North Aegean.

9) Peloponnese.

10) South Aegean.

11) Thessaly.

12) Western Greece.

13) Western Macedonia.

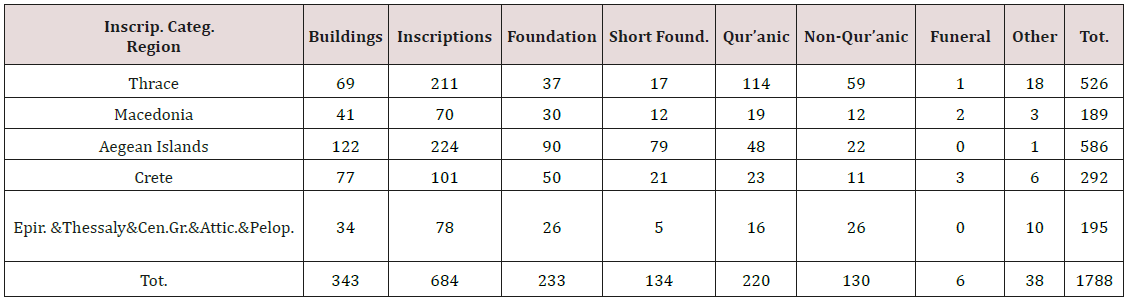

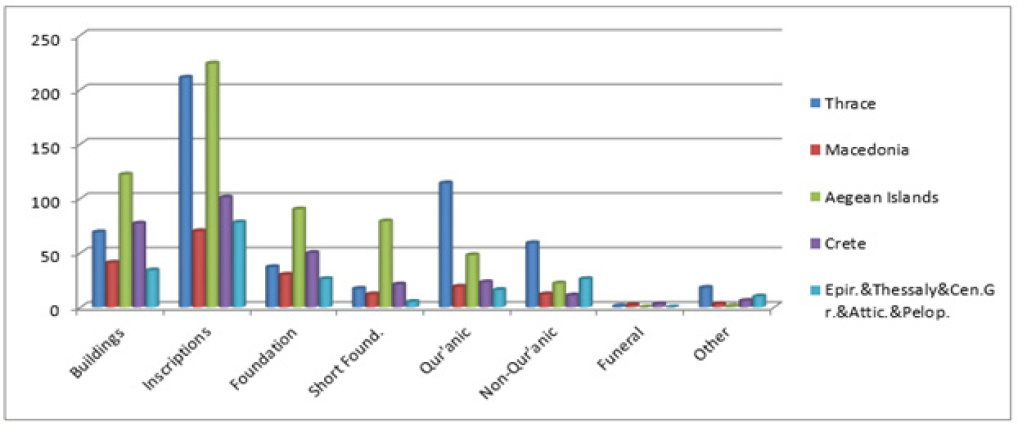

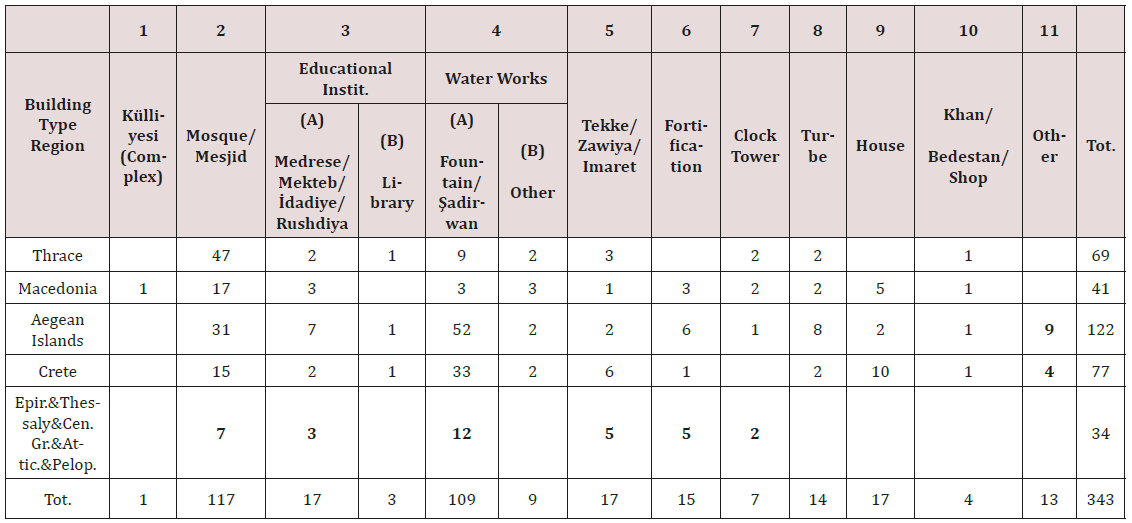

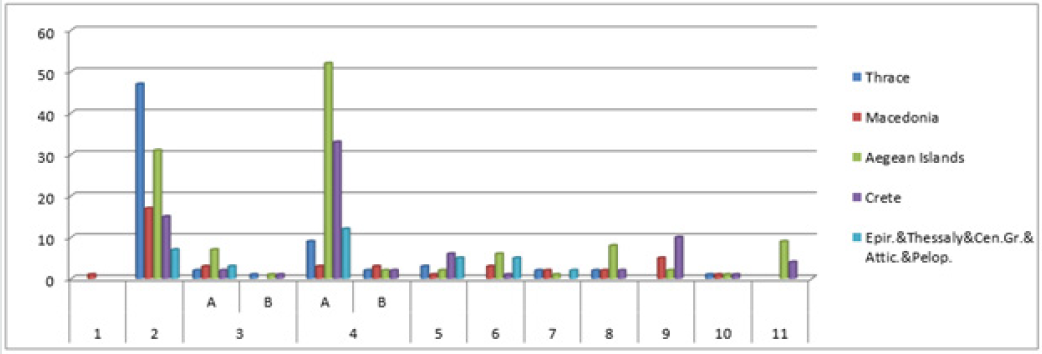

Considering the extant inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece, the focus of this research, we can divide the Greek territories geographically into five main groups (Table 1, 2; Charts 1, 2):

Table 1: Geographical proportion of inscriptions of Ottoman buildings in Greece considering their content (@ Ahmed Ameen 2019).

Chart 1: Geographical proportion of inscriptions of Ottoman buildings in Greece considering their content (@ Ahmed Ameen 2019).

Table 2: Geographical proportion of inscriptions of Ottoman buildings in Greece considering their function (@ Ahmed Ameen 2019).

Chart 2: Geographical proportion of inscriptions of Ottoman buildings in Greece considering their function (@ Ahmed Ameen 2019).

1) Thrace.

2) Macedonia.

3) Aegean Islands.

4) Crete.

5) Epirus, Thessaly, Central Greece, Attica and Peloponnese.

And there are no extant Ottoman inscriptions in Ionian Islands.

Analyzing the statistics of the inscriptions of Ottoman buildings in Greece geographically concludes that the numbers of the extant inscriptions correspond to those of the surviving ottoman architectural heritage in the same regions. The largest amount of surviving Ottoman inscriptions is found in the Aegean Islands (224 inscriptions), Thrace (211 inscriptions), Crete (101 inscriptions), Macedonia (70 inscriptions), and finally the last group (78 inscriptions) in Epirus, Thessaly, Central Greece, Attica and Peloponnese.

The highest number of surviving Ottoman inscriptions in the Aegean Islands and Crete is obviously thanks to the large number of well-maintained fountains ‘çeşme’. Thus the highest number of foundation and short foundation inscriptions is found in the Aegean Islands and Crete. But the largest amount of religious inscriptions, including both qur’anic and non- qur’anic, are found in Thrace; in which the largest amount of Mosques that still function, where the Greek Muslim minority live. Thus, the regions that still have Muslim minorities in Greece and those located near present-day Turkey have the highest numbers of existing Ottoman inscriptions. Neighbourly relationships and consequent economic relations played a role in preserving the Ottoman architectural heritage including inscriptions in these regions. The limited number of existing Ottoman inscriptions in Central Greece, Peloponnese and Thessaly is due to the liberation of these regions being earlier than those of other Greek regions, as well as their early revolutionary wars against the Ottomans. There is an inverse geographical relationship between the cultural aversion against ‘Turkish’ objects and the number of existing Ottoman inscriptions. This number is decreased from East to West.

The city of Ioannina ‘Yanya’ is an exception in Epirus, northwestern Greece, with a remarkable and well preserved surviving Ottoman epigraphic heritage. This obviously reflects Ioannina’s own historical contexts, which were different from other Greek regions either during the Ottoman rule or after the incorporation into the Greek State in 1913.

A Suggested Methodology in Cataloguing the Corpus of Inscriptions

Inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece, in our projected corpus, will be catalogued following the aforementioned regional approach, dealing with each structure separately. It provides, as possible, for each given inscription a recent photo(s), the deciphering, an English translation, and a commentary concluding with a list of its significant literature.

Since it is not possible to tackle with each one among the 684 surveyed inscriptions in a detailed study; thus it basically catalogues the raw material and makes it available for scholarly community. A group of inscriptions were erased, as many fountains in Lesvos and the Clock tower of Preveza, or covered with later inscriptions as the inscription above the door of left room of Ghazi Evrenos Imaret at Komotini, or damaged as the foundation inscription of the Ottoman Medrese at Athens, and some inscriptions of the Ierapetra Mosque. These inscriptions require using advanced technological tools and materials of cleaning and photographing to be readable. These tools are not available to me; thus such inscriptions will included without full or partially deciphering, or English translation.

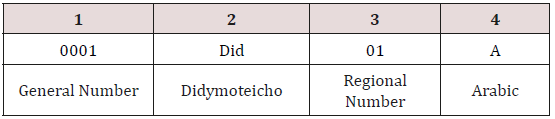

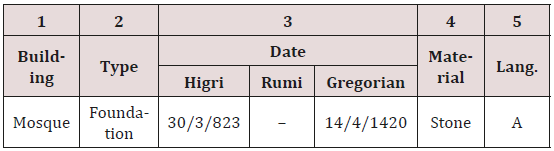

This paper suggests a new codification for the inscriptions of the Ottoman buildings in Greece; facilitating the upcoming research and digitizing these inscriptions. Each inscription will acquire this new codification ID. This ID will refer to the analysing of the inscription as the following example “0001Did01Ar”; hence this ID is composed of four parts as shown in the next table: (Table 3)

So that, the first four-digits number refers to a serial number consequence in the whole corpus of Ottoman buildings inscriptions in Greece, then a three-letters abbreviation referring the main regional unit (city) where the inscription belongs, thereafter a twodigits number states the number of this inscription among those of the same regional unit, and finally the abbreviation of the main language of the inscription, whereas the A=Arabic, O=Ottoman, P=Persian, G=Greek, I=Italian, F=French, TR=Modern Turkish, B=Bilingual, and T=Trilingual. This code will be mentioned as a Corpus ID.

So, each given inscription in this estimated corpus will be catalogued, as possible, through eight main items comprising: 1) Corpus ID: Caption of the inscription, 2) Regional Unit Name, 3) Basic Data, 4) Photo(s), 5) Reading “Text,” 6) Translation(s), 7) Commentary and 8) Bibliography as shown in the following example: Inscription (X)

Corpus ID: Caption of the inscription

Is the codification ID of the inscription –as noted earlier in this paper-followed by a caption describes the inscription. e.g. 0001Did01A: Main foundation inscription of Sultan Mehmed Çelebi Mosque at Didymoteicho

I. Regional Unit Name

This item states the first-level administrative entity with the corresponded ottoman names, to which the inscription belongs, then the second-level unit, afterward the location/Site of the inscription and its current condition.

This summary table provides the basic data of the inscription including: column 1: the type of the building, column 2: indicates the type of the inscription, column 3: divided into three subcolumns, provides the date in the three calendars cited in ottoman inscriptions; the Rumi date characterizes late Ottoman inscriptions, and will be stated only if cited in the given inscription, then column 4: shows the material on which was the inscription executed, and column 5: shows its language as explained in the corpus ID.

III. Photo(s)

Recent photo(s) if available is provided, either a reproduction of an old photo. For those mentioned by Evliya Çelebi but disappeared now, and there is no preserved old photo, will give the related parts of his manuscript.

IV. Deciphering “Text”

The text of the inscription is reproduced as original in its own language. If it is previously published, I will only refer to the related reference.

V. Translation(s)

As possible, English translation of the inscription is provided, but if it is previously published in whichever language, we will just refer to the corresponded reference.

VI. Commentary

Commentary comprises remarks, if required, on the building to which the inscription belongs, the content of the inscription and the previous significant studies.

VII. Bibliography

In bibliography citing where the inscription was previously published, described and/or studied.

Conclusion

The immense amount of the surviving inscriptions of the ottoman buildings in Greece which are not known to most scholars in Islamic epigraphy is the main motive of writing this article. These inscriptions comprise a rich material to study the Ottoman heritage in Greece over almost five centuries. The 684 inscriptions surveyed in this paper and analysed in quantitative method show their exceptional value taking into account their language and content. These inscriptions belong to 343 Ottoman buildings allover Greece and compose 1788 different texts. This paper is a part of a postdoctoral research on the same topic will be published soon as a corpus of Islamic inscriptions in Greece.

Read More About Lupine Publishers Journal of Anthropological and Archaeological Sciences Please Click on Below Link:

https://journalofanthropologicalsciences.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.