Lupine Publishers| Online Journal of Neurology and Brain Disorders (OJNBD)

Abstract

Rationale and objective: Epileptic seizure disorders have become an increased source of concern in veterans given their relative high exposure to traumatic brain injury (TBI). 40% of adults with focal epilepsy are expected to develop treatment-resistant epilepsy (TRE), which can be amenable to treatment with epilepsy surgery. Yet, epilepsy surgery in veterans with epilepsy (VWE) is performed less frequently than in non-veterans with epilepsy. One possible explanation may be that when seizures begin after the age of 50, seizure freedom is likely to occur in 70% of patients. The purpose of this study was to examine whether the frequency of treatment-resistant epilepsy was different in veterans and to identify potential variables that may account for this difference.

Methods: In this retrospective study we included 157 veterans followed in the outpatient clinic of the Miami Epilepsy Center of Excellence Veterans Health Administration. Data collected from the medical records included age at onset of epilepsy, etiology, seizure type and epilepsy syndrome, response to pharmacotherapy, presence of psychiatric co morbidities (classified as mood disorders, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, polysubstance abuse and other), antiepileptic regimen and adherence to medical treatment.

Results: Among the 157 patients, the mean age was 56.7 (±15.4) years and 140 (88.5%) were males; 119 patients (75.7%) had focal epilepsy presenting with complex partial with or without secondarily generalized tonic-clonic (GTC) seizures. TRE was identified in 25 patients (15.9%; 95% confidence interval: 11.0% to 22.5%); being a woman (p<0.01) and having focal epilepsy (p=0.04) were the only two significant variables associated with the development TRE.

Conclusion: In this study, the prevalence of TRE in this cohort of veterans was lower than that reported in the general epilepsy population. These findings need to be replicated in a larger study that includes the 16 VA Epilepsy Centers of Excellence.

Keywords: Focal epilepsy; Treatment resistant epilepsy; Major depressive episode; Traumatic brain injury; Posttraumatic stress disorder

Abbrevations: TBI: Traumatic Brain Injury; TRE: Treatment Resistant Epilepsy; VWE:Veterans with Epilepsy; GTC: Generalized Tonic Clonic; ILAE: International League against Epilepsy; PWE: Patients with Epilepsy; AEDs: Antiepileptic Drugs; PTSD: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Introduction

Epileptic disorders have become an increased source of concern in veterans given the relative high exposure to traumatic brain injury (TBI), particularly because of the increased number of veterans who have suffered from serious TBI in the course of the wars in Aphganistan and Iraq. Furthermore, TBI can often result in the development of treatment-resistant focal epilepsy (TRE), for which epilepsy surgery can at times be one of the potential treatments. Yet, the use of epilepsy surgery among the 16 VA Epilepsy Centers of Excellence during fiscal year 2016 revealed only 8 surgical procedures in veterans with epilepsy (VWE) among a total of 5.980 unique patients seen during 2016 [1]. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether TRE in VWE followed at one Epilepsy Center of Excellence differed from that reported in the general population of patients with focal epilepsy and if so, to identify potential causes for such difference.

The international League against Epilepsy (ILAE) proposed the new definition of TRE as a failure to reach seizure remission after adequate trials of two tolerated, appropriately chosen and used antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) [2]. It is estimated that between 30% and 40% of patients with epilepsy (PWE) fail to reach seizure freedom, despite multiple trials with AEDs [3]. Several variables may contribute to the development of intractability, including lack of response to the first AED, specific syndromes, symptomatic etiology, family history of epilepsy, psychiatric co morbidity, high frequency of seizures, and early age at onset of epilepsy [4,5]. These observations suggest that prognosis of the seizure disorder can often be determined in the early stages of the disease. Recognition of these variables has a direct bearing on the management of these patients, as they may ensure an early referral for a pre-surgical evaluation and when possible, may shorten the medico-social and economic burden of intractable epilepsy [6]. On the other hand, some studies have suggested that late-onset epilepsy (beginning after the age of 60) may be more responsive to medical management than epilepsy diagnosed during adolescence and early adulthood [7-9].

Methods

This was a retrospective cross-sectional study. We reviewed the medical records of every consecutive patient with epilepsy followed at the outpatient epilepsy clinic of the Miami VA Healthcare System (VAHS) Epilepsy Clinic over a period of 24 months (January 2010 to January 2012). The study was approved by the Miami VAHS institutional review board. Two Board-certified epileptologists confirmed the diagnosis of epilepsy using the ILAE criteria (2010), based on the clinical history, neuro imaging data and electrographic recordings. The data extracted from the medical records included demographic variables (age, gender, ethnicity) epilepsy-related variables (seizure type(s) and epilepsy syndrome (focal or generalized), etiology of the seizure disorder (unknown, remote symptomatic [tumor, stroke, TBI, or “other”] or idiopathic), age of onset of epilepsy, co morbidities (medical, cognitive and psychiatric co-morbidities [classified as mood and /or anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and polysubstance abuse/dependence, other] AED treatment, were recorded. We used the ILAE definition of TRE cited in our Introduction [2]. We defined epilepsy “in remission” as the absence of seizures in the last two years from the time the patient was evaluated at the epilepsy clinic. Of note, any patient with persistent seizures and/or in whom the clinical semiology of their seizures was not typical of an epileptic seizure underwent a diagnostic video-EEG monitoring study to establish if these events were epileptic or non-epileptic events and if epileptic seizures, to identify the type of seizures.

In this study 15 of the 25 patient with TRE underwent video- EEG monitoring, including all the women in this case series. The clinical characteristics of seizures of the 10 patients with TRE who did not have a video-EEG monitoring study were typical of epileptic seizures. Patients who were thought to have psychogenic non-epileptic seizures were excluded from the study. In addition, 9 patients who had persistent seizures but had only undergone one optimal trial with an AED were excluded. A total of 157 patients with epilepsy were included in this study. Demographic, epilepsy-related variables and data of psychiatric co morbidities were extracted from the medical record and included: age, gender, ethnicity, race, seizure type (focal, generalized), whether the seizure disorder was idiopathic, Symptomatic or unknown), age at onset of epilepsy, list of current AEDs and dosage (s), and response to each AED trial. Data of psychiatric co morbidities included mood disorder, anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), polysubstance abuse and other psychotic spectrum disorders such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and psychosis NOS.

Data Management and Analysis

Age was treated as a continuous variable and t tests for independent groups were used to compare data between TRE and seizure free group. Categorical variables were summarized by accumulated percentages. Chi-square or Fisher exact tests were used to compare the categorical variables for association between seizure freedom and clinical factors. Where the expected counts were less than 5, Fisher exact tests were performed. For all analyses, p≤ 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

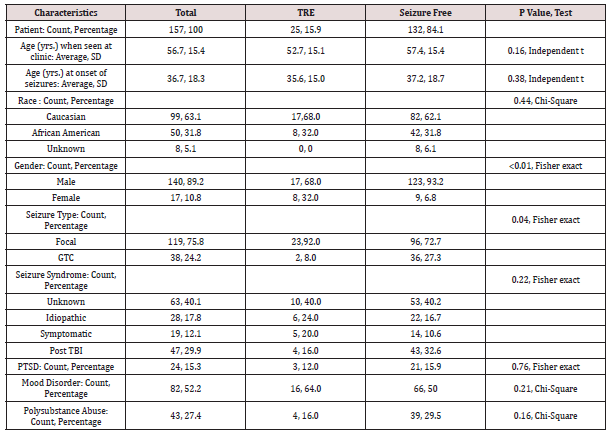

Among the 157 patients included in our analysis 25 patients met criteria of TRE and 132 were seizure-free. (Table 1) summarizes the data pertaining to the demographic, epilepsy-related and co morbidities variables among the seizure-free and TRE patients. The prevalence of patients with TRE was lower (15.9%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 11.0% to 22.5%) than that reported in multiple studies, which ranges between 30% and 50%) (2, 10-12). Had we included in our analysis the 9 patients with persistent seizures that had been tried on one AED, the percentage of patients with TRE would have only increased to 21.6% (95% CI: 15.9% to 28.7%), still below the expected rate. Two variables were significantly associated with the development of TRE in our patients: female gender (47%) and focal epilepsy (92.0 %). See (Table 1) for statistical analysis.

Table 1: Characteristics of Study Cohort (N=157).

TRE: Treatment resistant epilepsy; SD: Standard deviation, GTC: Generalized tonic clonic

TBI: Traumatic brain injury, PTSD: Post traumatic stress disorder

Percentages are reported to one decimal digit

Discussion

Epilepsy has become a neurologic disorder of great concern among veterans, given the large number of soldiers returning from the wars in the Middle-East where they suffered TBI [10]. This study was developed to assess the cross prevalence of TRE among outpatient veterans followed in a VA Epilepsy Center of Excellence and compare it to that published in populations of non-veteran PWE. To our surprise, the prevalence of TRE was lower in our patients than that published in studies conducted in non-veterans [11,12]. The second surprising finding was the observation that TRE was significantly more prevalent among women veterans. At this point, we cannot explain the reasons for a lower prevalence of TRE in our patients and our findings will need to be replicated in larger prospective studies. Of note, neither the cause of epilepsy, nor the age of onset of the seizure disorder failed to account for a better seizure control in our cohort, as suggested by several published studies that had suggested that elderly patients are more likely to have good outcomes [13,14].

In PWE, those with symptomatic or cryptogenic epilepsy are more likely to be medication resistant than those with idiopathic epilepsy [8,15]. In our study, the etiology of seizures did not play a factor in developing intractability. Traumatic brain injury was the most common cause of symptomatic epilepsy but failed to represent a predictive factor of intractability-perhaps because there are few cases of penetrating head injury, which is most commonly associated with medial intractability. Initial seizure frequency has been identified as a significant prognostic factor for TRE in the literature [16]. Unfortunately, we were not able to investigate this issue in a reliable manner because most of the patients were diagnosed somewhere else several years prior to our evaluation and the information was not found in the retrospective review of the medical records. This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study. Second, we relied on the patients’ self (and or family members’) reports of their epileptic seizures. Yet, patients may have seizures and not be aware of their occurrence, which could result in an under-estimation of seizure frequency. Third, our study was based on data from a single Epilepsy Center of Excellence. While these are the centers where veterans with TRE are referred for treatment in the VA system, our data will need to be replicated in a larger study that includes all 16 Epilepsy Centers of Excellence in the USA.

Conclusion

The findings of this study may suggest that TRE may be less frequent in VWE than in other published cohorts and that women veterans may be at greater risk. These findings have to be considered as preliminary but deserve a careful investigation in a larger study that may include the other 15 Epilepsy Centers of Excellence of the VA and which can be compared with non-veteran populations.

Read More About Lupine Publishers Online Journal of Neurology and Brain Disorders (OJNBD) Please Click on Below Link: https://brain-disorders-lupine-publishers.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.