Increases in oil and gas drilling have resulted in large quantities

of oil base "mud" (OBM) to be disposed of. Land application of OBM to

agricultural land is a common disposal technique that presents agronomic

and environmental challenges since the material is rich in total

petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH). Leaching of lower molecular weight

hydrocarbons, mainly benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX),

is a concern due to their relatively low octanol: water partition

coefficients. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of

rainfall regime and TPH loading rate on TPH degradation and BTEX

leaching after OBM application. An OBM was characterized for TPH, BTEX,

and trace metals. A soil column study was conducted where OBM was

applied at five loading rates (0, 22,000, 45,000, 67,000, and 90,000 kg

TPH ha-1) and was subjected to four moisture regimes. OBM

samples were taken at day 0, 7, 30, 60, and 91 to monitor TPH

degradation. Leachate samples were taken at day 0, 14, 28, 35, 49, 56,

63, 77, and 84 to monitor electrical conductivity (EC), pH, metal

concentrations, and BTEX concentrations. After 60 days, a maximum TPH

degradation of 35% was measured. Leachate BTEX concentrations increased

as TPH application rate increased and was mostly undetectable by day 28.

Leachate EC increased over time and with increasing TPH rates. TPH rate

had no effect on leachate pH. OBM loading rates had the greatest effect

on TPH degradation and BTEX leaching. Under our experimental

conditions, little risk of BTEX leaching from land applied OBM was

observed.

Abbrevations: OBM: Oil-Base Mud; TPH: Total

Petroleum-Based Hydrocarbons; BTEX: Benzene, Toluene, Ethylbenzene, and

Xylene; OCC: Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC); EC: Electrical

Conductivity

Introduction

Currently, the United States is experiencing a boom in oil and gas

drilling. In 2013, there were approximately 910,000 and 4,900 onshore

and offshore oil and natural gas wells, respectively, that produced

nearly 16 million m3 of oil and 665 billion m3 of

natural gas [1]. When drilling activity increases, an increase in the

production of drilling wastes result, specifically drilling fluids and

drill cuttings (i.e. "mud"). A study conducted by the American Petroleum

Institute in 1995 estimated that around 150 million barrels of drilling

wastes were generated on-shore in the United States alone [2]. In the

oil and gas industry, drilling mud is utilized to help cool the drill

bit, maintain borehole pressure, and aid in bringing drill cuttings to

the surface where the fluids and cuttings can then be separated [3].

Drilling muds are composed of a base liquid (water or diesel fuel) with

other potential additives such as bentonite, barium sulfate, cotton seed

hulls, and calcium hydroxide, which may be used for specific drilling

conditions [4]. When diesel fuel is the base solution for drilling mud,

the mud is called "oil base mud" (OBM). OBM is typically utilized when

drilling depths exceed 1500 m or during horizontal drilling. OBM is

re-used by drillers for as long as possible due to the high cost of

production.

Once the OBM is spent and can no longer be used in drilling, it must be properly disposed of. On average, 340 m3

of OBM are produced from a typical southeastern Oklahoma natural gas

well at depths ranging from4200-5200 m deep [5]. Some of the products

added to the mud may be harmful, and therefore need to be properly

handled [6]. Hence, there are two options for mud disposal: land

application and burial. Burial of the waste can occur onsite in "reserve

pits" or at commercial facilities. In general, onsite reserve pits are

only allowed for water-base mud, not OBM. Land application is the most

common method of OBM disposal in Oklahoma. The purpose of land applying

OBM is to allow soil microorganisms to degrade petroleum hydrocarbons

(i.e. "total petroleum hydrocarbons"; TPH). In Oklahoma, regulations for

the land application of OBM are controlled by the Oklahoma Corporation

Commission (OCC). OBM land application rates are limited based on

loading of TPH, chlorides, and solids (Oklahoma administrative code and

register, Title 165:10-7-26). Furthermore, the OCC requires that OBM be

mixed with a bulking material such as lime or gypsum, at a ratio of 3:1

OBM: bulking material. Although TPH is taken into account when applying

OBM, there is still a potential for the over-application of low

molecular weight hydrocarbons: benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and

xylene (BTEX). Benzene is a known human carcinogen and all BTEX

components are known to cause neurological effects [7]. BTEX chemicals

are prone to leaching due to their relatively low octanol: water

partition coefficients [8] and therefore pose a threat to drinking

water. In addition to loading limits, there are also several site

suitability requirements such as soil texture, depth to groundwater and

limiting layers, slope, soil sodium concentrations, and proximity to

surface waters. Although thousands of hectares are currently receiving

OBM, there has been relatively little research conducted on the

degradation of TPH and the leaching of BTEX after land application of

OBM.

Uncontrolled application rates could lead to soil TPH concentrations

that would be detrimental to soil and water quality leading to

environmental issues. Penet et al. [9] conducted a study that examined

biodegradation of hydrocarbons in the soil and found that microbes

degraded the straight chained hydrocarbons faster than the branched

chained hydrocarbons. Dou et al. [10] conducted a study focused on

anaerobic BTEX degradation under nitrate reducing conditions and

determined that BTEX could be biodegraded to undetectable concentrations

in 70 days if initial concentrations of BTEX were ≤ 100 mg kg'1

soil. Very few studies have dealt with TPH degradation and BTEX

leaching in soils after land application of OBM. Due to the hazardous

risks of TPH, specifically BTEX toxicity to humans and to the

environment, there is a need to examine TPH degradation and BTEX

leaching in soils after land application of OBM under different

scenarios such as multiple loading rates and moisture regimes. Thus, the

objective of this study was to determine the impact of rainfall regime

and TPH loading rates from OBM application on TPH degradation and BTEX

leaching.

Materials and Methods

A soil column study was conducted in Stillwater, Oklahoma in a

temperature controlled greenhouse. Soils were contained in 240 aluminum

soil columns that were 30.5 cm tall and 7.6 cm in diameter. Columns were

filled 15.2 cm with a sandy loam soil from Perkins, Oklahoma. The soil

series used in this experiment was Dougherty loamy fine sand (Loamy,

mixed, active, thermic Arenic Haplustalfs). Glass wool and aluminum

screen with a 7.6 cm hose clamp was placed on the bottom of all columns

in order to prevent soil from leaching out. The experimental design was a

randomized complete block with factorial structure. There were three

replications of each treatment. The OBM sample was characterized for pH,

electrical conductivity (EC), total soluble salts (TSS), and total

solids content, total and water extractable metals and total chloride.

OBM pH and EC were measured using pH and EC probes with a solid:

solution ratio of 1:5 and an equilibration time of 45 min. The OBM was

analyzed for total P, K, Mg, Ca, Na, Mn, Cu, Fe, Zn, S, Al, Ni, B, As,

Cd, Cr, Ba, Pb, and Mo using the EPA 3050 acid digestion method followed

by solution analysis with inductively coupled argon plasma analyzer

[ICP-AES; Spectro Ciros, Mahwah, NJ]. Water extractable metals and total

chloride were extracted with de-ionized (DI) water using a 1:10 solid:

solution ratio for 1 hour followed by ICP-AES analysis on the metals and

colorimetric flow-injection analysis (Lachat Quick Chem 8000, Loveland,

CO) for chloride.

Prior to the application of OBM, BTEX and TPH concentrations were

analyzed. Total petroleum hydrocarbons were extracted with hexane at

1:10 solids: solvent ratio, plus addition of 0.5 g Na2SO4

for 5 minutes on a reciprocating shaker followed by centrifugation for

10 minutes. Five mL of the resulting supernatant was equilibrated for 2

minutes with 1 g of silica gel in a glass tube for removal of polar

organic compounds. The solution was then analyzed for TPH using infrared

spectroscopy (ASTM method D 7066) with the Infra Cal TOG/TPH analyzer

(model HATR-T2, Wilks Enterprise Inc., East Norwalk, CT). Random samples

were duplicated and check samples were utilized in order to assure

precise and accurate results. Initial benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene,

o-xylene, m, p-xylene and TPH concentrations were 2.65, 23, 35, 64, 94,

and 161,558 mg kg- 1. Treatments included five TPH (i.e. OBM) loading rates and four rainfall regimes.

Soil columns were harvested for OBM analysis of TPH at four different

times. Oil-base mud was applied onto an aluminum screen which rested on

top of the soil that allowed soil to contact the OBM, yet prevented

mixing and dilution of the applied OBM TPH with the soil. This allowed

for removal of the OBM throughout the incubation in order to test for

TPH degradation. Oil-base mud loading rates were applied to achieve a

TPH application of 90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg

TPH ha-1. Each column was treated with one leaching event per month

which consisted of application of 1.5 pore volumes of tap water. In this

study, the term "moisture regime" indicates the number of non-leaching

wetting events that occurred per month. Moisture regime levels 4, 3, 2,

and 1 had 3, 2, 1, and 0 non-leaching wetting events per month, which

consisted of 0.5 pore volumes of tap water. These non-leaching wetting

events are important because they can move soluble constituents within

the column, but not out of the column, as well as provide moisture for

microorganisms that may degrade TPH. Collected leachate was analyzed for

benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene using the EPA 8021B method

followed by solution analysis with gas chromatography with a photo

ionization detector (GC-PID). In addition, leachate was also analyzed

for Na, Ca, Mg, K, SO4, B, P, Fe, Zn, Cu, Mn, Al, Mo, As, Cd, Co, Cr,

Pb, and Ba via ICP-AES. OBM was harvested on top of the aluminum screens

at 7, 30, 60, and 90 days after application and analyzed for TPH

concentrations (mg TPH kg mud-1) with the Wilks TOG/TPH IR Analyzer. The BTEX concentrations in harvested OBM samples were measured 7 days after application.

Statistics

Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) methods were utilized in PROC GLM [11]

to analyze the effects of OBM loading rates and moisture regimes on TPH

degradation and BTEX leaching. When the main effects or interactions of

OBM loading rates and moisture regimes were significant, treatment means

were separated using pair wise comparisons via Duncan's multiple range

test. Statistical decisions were made at a=0.05.The data analysis for

this paper was computed using SAS software.

Results and Discussion

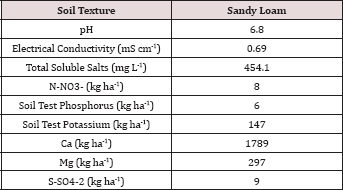

Background Soil Properties

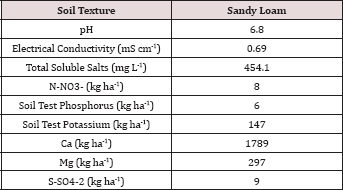

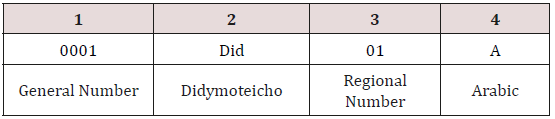

Table 1: Background chemical analysis of the soils used in the BTEX leaching column study.

The soil utilized in the BTEX leachate study was a sandy loam texture

(Table 1) which has great potential for the leaching of soluble

constituents. The OCC states in the Oklahoma administrative code and

register, Title 165:10-7-26 that OBM must be incorporated into the soil

after application; incorporation of the OBM leads to increased mixing

(dilution) of the OBM into the soil and faster hydrocarbon degradation.

Due to the large hydraulic conductivity of the sandy loam soil and the

fact that the OBM was not incorporated made this study a worst-case

scenario for land application of OBM with respect to BTEX leaching and

hydrocarbon degradation. The background soil had N-NO3-, P, and K

concentrations of 8, 6, and 147 kg ha-1, respectively. Soil

pH was 6.8 and was in the optimal range for microbial degradation and

limiting metal migration in the soil [12].

Background Oil-Base Mud Properties

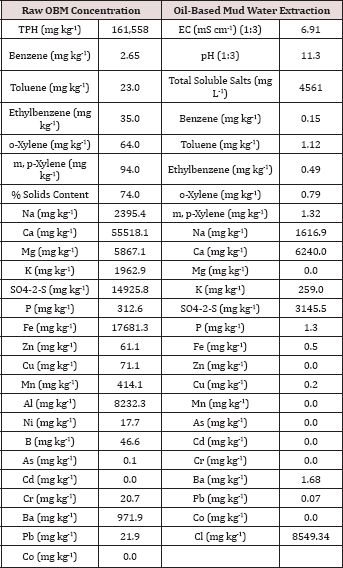

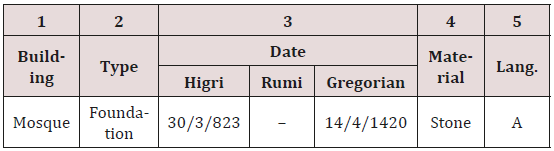

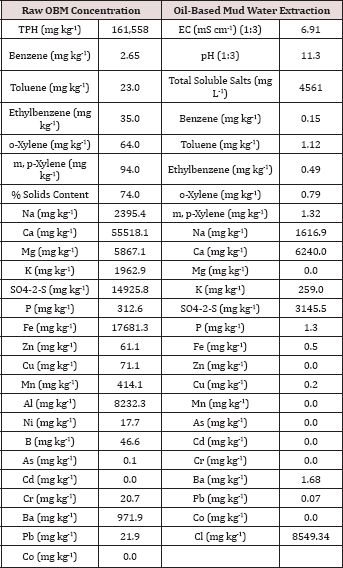

Table 2: Characterization of the raw (solids plus

liquid) and the water extractable portion of the oil-base mud (OBM) used

in the BTEX leaching column study. All water extraction results were

obtained by using a 1:10 solids to DI water ratio unless otherwise

noted.

The initial chemical analysis of the raw OBM and water extractable

portion are listed in Table 2. The raw OBM had an initial TPH

concentration of 161,558 mg TPH kg'1 and consisted of 74% solids. The raw OBM had a benzene concentration of 2.65 mg kg-1 which was higher than the inhalation limit of 0.8 mg kg-1 established by the U.S. EPA [13] and for risk to groundwater by leaching (0.03 mg kg-1; [14]). The water-soluble benzene concentration (0.015 mg L-1) was higher than the groundwater limit of 0.005 mg L-1

set by the Oklahoma Guardian [15]. Calcium was the dominant cation in

both the raw solid and water extractable portion of the OBM. Chloride

and sulfate were the two most abundant anions in the water extractable

portion of the OBM. All heavy metal concentrations (Zn, Cu, Ni, As, Cd,

Cr, and Pb) measured in the raw OBM were below EPA 503 thresholds for

"exceptional quality" bio solids, indicating that there is only slight

risk of metals contamination from land application of this OBM sample

[16]. In fact, heavy metal concentrations in the OBM were in the normal

range typically found in soils [17].

Degradation of total petroleum-based hydrocarbons with oil-base mud application

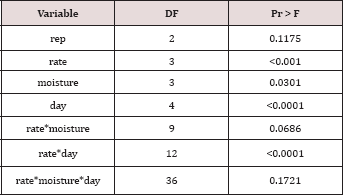

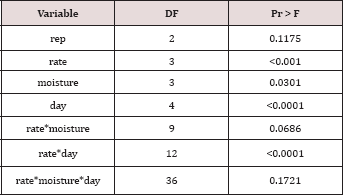

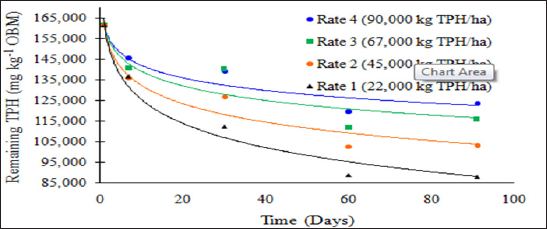

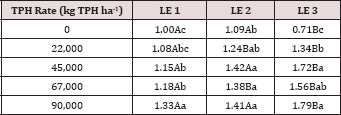

The main effects of TPH rate, moisture regime, sampling day (i.e.

time), and the two-way interaction of rate*day were significant at α =

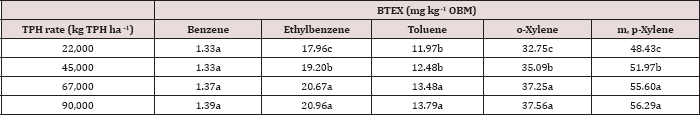

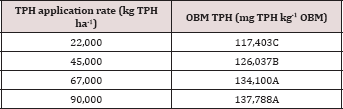

0.05 for TPH concentration (mg kg-1 OBM). An ANOVA table with the complete list of main effects and interactions for TPH concentration (mg kg-1 OBM) are listed in Table 3.The main effect of TPH application rate (kg TPH ha-1) on overall TPH concentration (mg TPH kg’1

OBM) was significant (P ≤ 0.05) and is shown in more detail in Table 4

(averaged across all sampling times and moisture regimes). TPH

application rate 1 (22,000 kg TPH ha-1) had a significantly

lower TPH concentration than all other rates and was closely followed by

application rate 2 (45,000 kg TPH ha-1) which was also significantly different than all other application rates. Application rate 3 (67,000 kg TPH ha-1) and rate 4 (90,000 kg TPH ha-1)

had the highest TPH concentrations but were not significantly different

than each other. The decreased TPH degradation displayed by application

rates 3 and 4 were likely due to reduced contact between OBM and the

soil surface (i.e. lower OBM: soil contact area), resulted in less TPH

degradation [18,19].

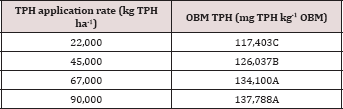

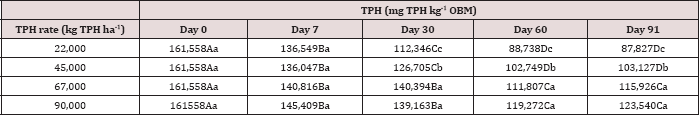

Table 3: Mean total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) concentrations (mg kg-1

OBM) in the surface applied OBM averaged across moisture regime and

sampling day for each TPH application rate. OBM loading rates were

applied at 90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1.

The treatments were subjected to four different moisture regimes. OBM

was sampled at 0, 7, 30, 60, and 90 days after application. Uppercase

letters represent mean separation of TPH concentration (mg TPH kg-1 mud) between TPH rates. Statistical decisions were mad at P = 0.05.

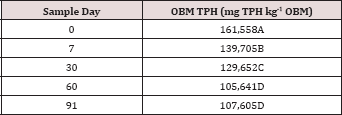

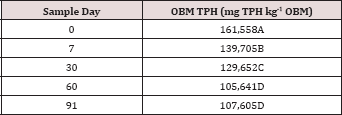

Table 4: Mean total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) concentration (mg TPH kg-1

OBM) at each sample day averaged over moisture regime and TPH

application rate. OBM loading rates were applied at 90,000, 67,000,

45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The treatments

were subjected to four different moisture regimes. OBM was sampled at 0,

7, 30, 60, and 91 days after application. Uppercase letters represent

mean separation of TPH degradation (mg TPH kg-1 OBM) between all sample days. Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

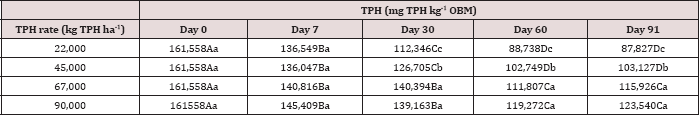

Table 5: Mean total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) concentration (mg TPH kg-1

OBM) averaged across moisture regime and compared between sample day

and TPH application rate. OBM loading rates were applied at 90,000,

67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The

treatments were subjected to four different moisture regimes. OBM was

sampled at 0, 7, 30, 60, and 91 days after application. Uppercase

letters represent mean separation of TPH concentration between sampling

days at each TPH application rate. Lowercase letters represent mean

separation of TPH concentration between TPH application rates at each

sampling day. Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

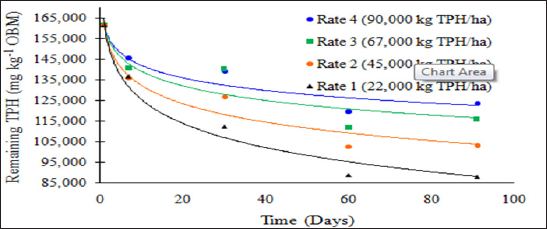

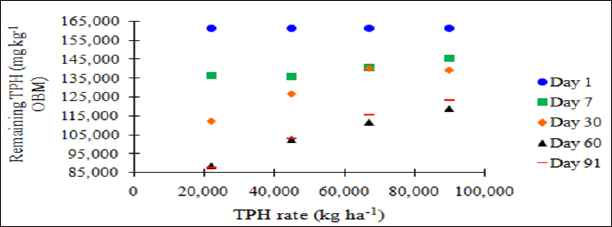

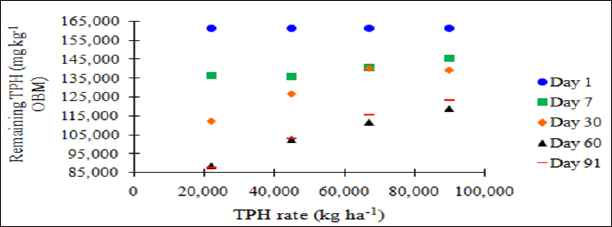

The main effect of sampling day (time) on overall TPH concentration

was significant (P ≤ 0.05) and is shown in further detail in Table 5

(averaged across all application rates and moisture regimes). As time

increases, a significant decrease in TPH concentration was observed

until day 60. Day 60 and 91 had a significantly lower TPH concentration

than all previous sampling days; however there was no significant

difference between day 60 and 91. Figure 1 and Table 6 illustrate the

insignificant degradation between day 60 and 91 for each application

rate. There was a large decrease in TPH concentration for all TPH rates

up until day 60. This plateau effect in degradation is likely due to the

consumption of microbial nutrients, probably nitrogen, which inhibited

further biodegradation of hydrocarbons. There were no significant

differences in TPH concentrations between TPH application rates at day 0

or 7. Significant difference between TPH rates occur at day 30 and

continue through day 91. TPH application rate 1 had the lowest TPH

concentration followed by rate 2 and rate 3, while rate 4 is not

significantly higher than rate 3. The TPH application rates 1 and 2

possess a higher proportion of OBM in contact with the soil surface,

which may have improved degradation. Not only do TPH

rates 3 and 4 have lower OBM to soil contact ratios, which limited

microbial degradation of hydrocarbons. TPH concentrations for all

biodegradation of TPH, but the excessive loading rates could have

application rates at day 90 were higher than the Oklahoma Guardian

impeded oxygen flow into the soil which may have further restricted

thresholds established for non-sensitive soils (46,000 mg kg-1; [5]).

Table 6: Mean total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) concentration (mg TPH kg-1

OBM) averaged across moisture regime and compared between sample day

and TPH application rate. OBM loading rates were applied at 90,000,

67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The

treatments were subjected to four different moisture regimes. OBM was

sampled at 0, 7, 30, 60, and 91 days after application. Uppercase

letters represent mean separation of TPH concentration between sampling

days at each TPH application rate. Lowercase letters represent mean

separation of TPH concentration between TPH application rates at each

sampling day. Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

Figure 1: Mean remaining total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH)

concentrations in the OBM in mg kg-1 OBM. OBM loading rates were applied

at 90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The

treatments were subjected to four different moisture regimes. OBM was

sampled at 0, 7, 30, 60, and 91 days after application. TPH values are

for each sampling day and TPH application rate averaged over moisture

regime.

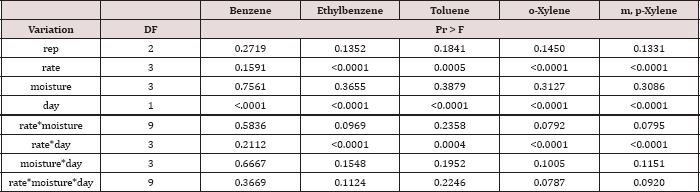

Changes in BTEX concentrations in the oil-base mud

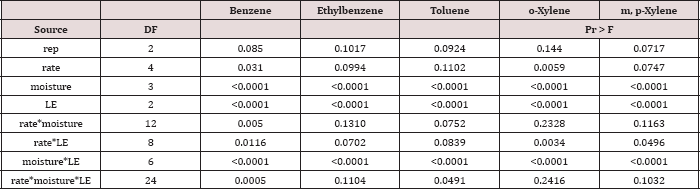

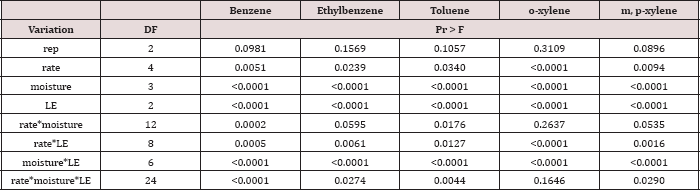

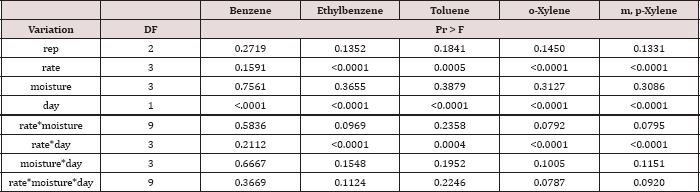

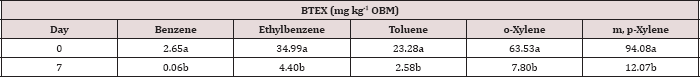

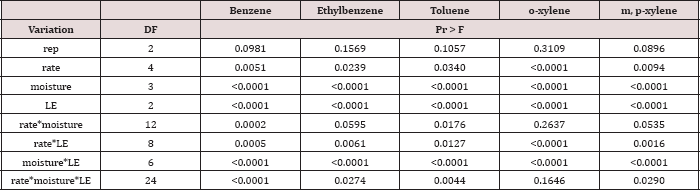

The main effect of sampling day on OBM BTEX concentration was

significant at α = 0.05. The main effect of TPH rate and the two-way

interaction of rate*day was also significant at α = 0.05 and is shown in

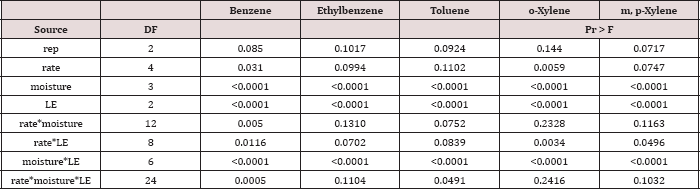

Table 7, which provides a complete list of ANOVA results for the main

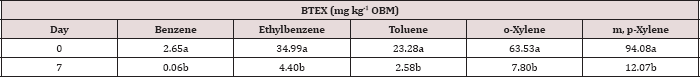

effects and interactions. Table 8 shows a significant decrease in BTEX

concentration (mg kg-1) for all BTEX constituents between day 0 and 7. These decreases in BTEX concentrations over

for inhalation and groundwater risks.

Table 7: ANOVA results for oil-base mud (OBM) benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, o-xylene, and m, p-xylene (BTEX) concentrations in mg kg-1 OBM for the BTEX leaching column study. Results are significant when (Pr ≤ 0.05).

Table 8: Mean benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, o-xylene, and m, p-xylene (BTEX) concentrations (mg kg-1

OBM) averaged across moisture regime and total petroleum hydrocarbon

(TPH) application rate and compared between each sampling day. OBM

loading rates were applied at 90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0

(control) kg TPH ha-1. The treatments were subjected to four

different moisture regimes. OBM BTEX was sampled at 0, and 7 days after

application. Lowercase letters represent mean separation for BTEX

degradation (mg kg-1 OBM) between each sampling day. Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

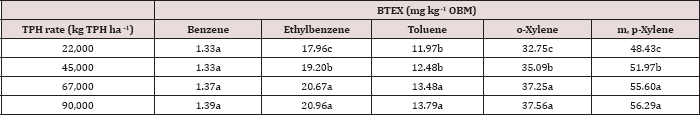

The main effect of TPH application rate (kg TPH ha-1) was significant (Pr ≤ 0.05) for OBM BTEX concentration (mg kg’1)

for every BTEX constituent except for benzene (Table 9), when averaging

over the two sampling days. TPH application rate 1 had significantly

lower concentrations of ethylbenzene, toluene, o-xylene, and m, p-xylene

than all other TPH application rates. The TPH application rate 2 had

the next lowest concentration values, rates. TPH application rates 3 and

4 had the highest concentrations of BTEX and were both significantly

higher than TPH rates 1 and 2, although not significantly different from

each other. Similar trends were noted regarding TPH concentrations

(Table 4). Higher BTEX concentrations (i.e. lower degradation) at the

highest application rates (3 and 4) likely occurred for the same reasons

as previously discussed for TPH degradation.

Table 9: Mean benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, o-xylene, and m, p-xylene (BTEX) concentrations(mg kg-1

OBM) at each total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) application rate for the

BTEX leaching column study. OBM loading rates were applied at 90,000,

67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The

treatments were subjected to four different moisture regimes. OBM BTEX

was sampled at 0, and 7 days after application. Lowercase letters

represent mean separation for BTEX concentration (mg kg-1 OBM) between each TPH rate. Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

Concentrations and loads of BTEX leached from applied oil-base mud

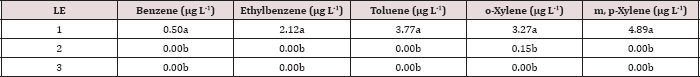

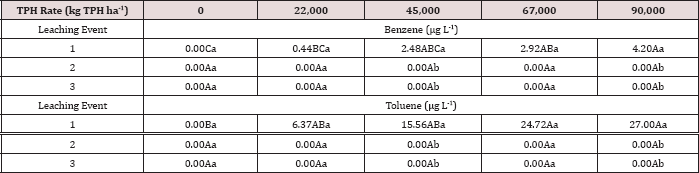

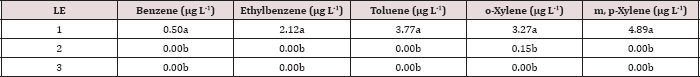

The main effects of TPH rate, moisture regime, leaching event, and

the interactions between each are shown in Table 10.The main effect of

leaching event was significant (P ≤ 0.05) for BTEX leachate

concentrations (μg L-1) and is shown in added detail in Table

11, averaged over TPH application rate and moisture regime.

Significantly higher concentrations of BTEX were measured at leaching

event 1 when compared to leaching events 2 and 3. For every BTEX

constituent except for o-xylene, leaching event 1 was

the only leaching event in which detectable levels of BTEX were measured

in leachate. All BTEX concentrations at leaching event 1 were low (<

5 ng L-1) and below the threshold limits for drinking water

established by EPA 816F regulations. It is noteworthy to mention that

each leaching event is an average of three leachate sampling days; a

higher leaching event number (e.g. leaching event 1, 2, and 3) also

indicates a greater amount of time that has occurred since application

of OBM. No BTEX was detected in leachate from leaching events 2 and 3

because it was either mostly volatized, degraded, or sorbed to soil

surfaces.

Table 10: ANOVA results for benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, o-xylene, and m, p-xylene (BTEX) leachate concentrations in (μg L-1) for the BTEX leaching column study. Results significant when (Pr≤ 0.05). LE = "leaching event".

Table 11: Mean benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, o-xylene, and m, p-xylene (BTEX) leachate concentrations (μg L-1)

averaged over total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) application rate and

moisture regimes and compared between leaching events. For the BTEX

leaching column study. OBM loading rates were applied at 90,000, 67,000,

45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The treatments

were subjected to four different moisture regimes which had one leaching

event per month. Lowercase letters represent mean separation between

leaching events for each BTEX constituent concentration (μg L-1). Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05. LE = "leaching event".

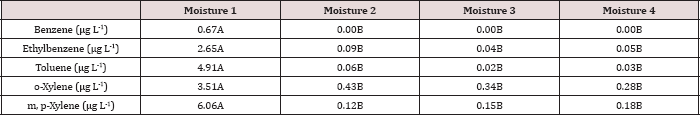

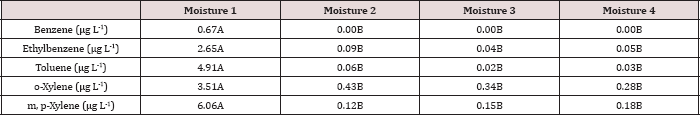

The main effect of moisture regime was significant (P ≤ 0.05) for BTEX leachate concentrations (μg L-1)

and is presented in further detail in Table 12. Moisture regime 1 (0

wetting events per month) showed significantly higher BTEX

concentrations than all other moisture regimes that received

non-leaching wetting events. The leachate concentrations of each BTEX

constituent at moisture regime 2, 3, and 4 were statistically the same.

However, the highest concentrations of BTEX observed in the leachate for

moisture was averaged over the first sampling day of each month (day 0,

35, and 63). Specifically, moisture regime 1 was sampled (i.e. leached)

on day 0, 35, and 63 and only had BTEX concentrations above 0 ng L-1

on day 0, which were the highest for the entire study. The highest BTEX

leachate concentrations from day 0 thus caused moisture regime 1 to be

significantly higher than the other moisture regimes. Again, this shows

the importance of time on BTEX degradation, volatilization, and sorption

to the soil.

Table 12: Mean ethylbenzene and toluene leachate concentrations (μg L-1)

averaged over total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) application rate and

leaching events and compared between moisture regimes. OBM loading rates

were applied at 90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH

ha-1. The treatments were subjected to four different

moisture regimes which had one leaching event per month. Uppercase

letters represent mean separation for ethylbenzene and toluene between

moisture regimes. Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

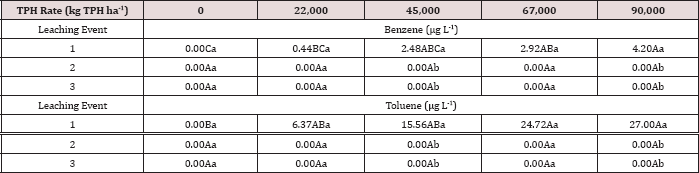

Table 13: Mean benzene and toluene leachate concentrations (μg L-1)

at moisture regime one comparing total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH)

application rates and leaching events for the BTEX leaching column

study. OBM loading rates were applied at 90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000,

and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The treatments were subjected

to four different moisture regimes which had one leaching event per

month. Uppercase letters represent mean separation of benzene and

toluene leachate concentrations between TPH application rates at each

leaching event within moisture regime one. Lowercase letters represent

mean separation of benzene and toluene leachate concentrations between

leaching events at each TPH application rate within moisture regime one.

Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

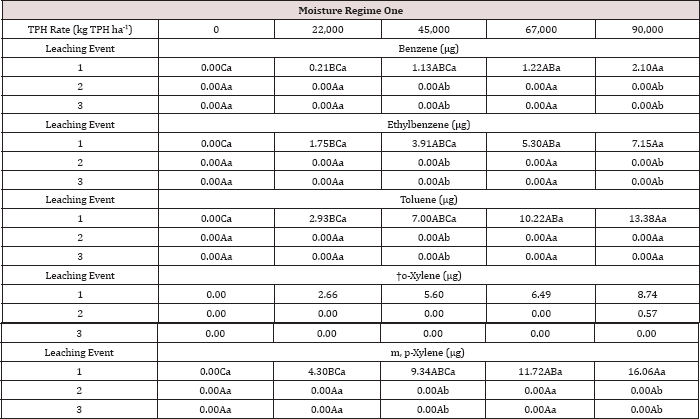

The three-way interaction of TPH rate by moisture regime by leaching

event was significant (P ≤ 0.05) for benzene and toluene leachate

concentrations (ng L-1; Table 13). Moisture regime 1 is the

only regime shown in Table 13 because this was the only moisture regime

that had significant amounts of BTEX in the leachate (Table 12). A

general trend of increasing concentrations of benzene and toluene in

leachate was observed as the rate of TPH application increased, for

leaching event 1. Leaching events 2 and 3 have no detectable

concentrations of benzene or toluene in the leachate. By the time

leaching events 2 and 3 occurred, all amounts of benzene and toluene

were lost via microbial degradation, volatilization, and sorption to the

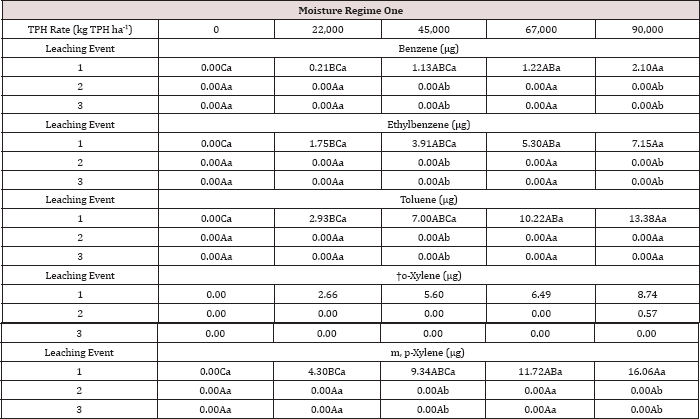

soil, or through leachate. The main effects of TPH application rate,

moisture regime, and leaching event on BTEX leachate loads and the

interactions between variables are shown in Table 14. The three-way

interaction of TPH rate by moisture regime by leaching event was

significant (P ≤ 0.05) for all constituents of BTEX except for o-xylene

and is shown in further detail in Table 15. Moisture regime 1 is the

only moisture regime listed due to the fact that this was the only

moisture regime that contained detectable concentrations in leachate

(Table 12). For leaching event 1, a general trend of increasing BTEX

loads is evident with greater TPH application rates.

Table 14: ANOVA results for benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene,

o-xylene, and m, p-xylene (BTEX) leachate loads (μg) for the BTEX

leaching study. Results were significant when (Pr ≤ 0.05). LE =

"leaching event".

Table 15: Mean benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, o-xylene, and

m, p-xylene (BTEX) leachate loads at moisture regime one, comparing TPH

application rates and leaching events. OBM loading rates were applied at

90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1.

The treatments were subjected to four different moisture regimes which

had one leaching event per month. "┼-"- o-xylene was not significant at P

= 0.05. Uppercase letters represent mean separation of BTEX loads (μg)

between TPH application rates at each leaching event, for moisture

regime one. Lowercase letters represent mean separation of BTEX loads

(^g) between leaching events at each TPH rate, for moisture regime one.

Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

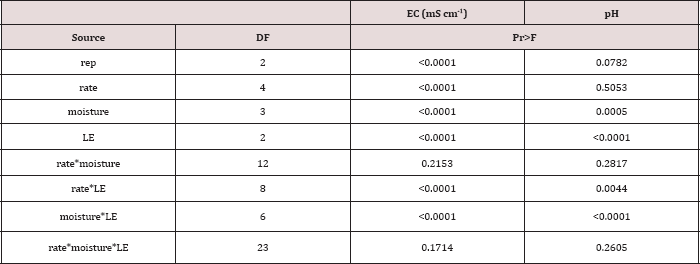

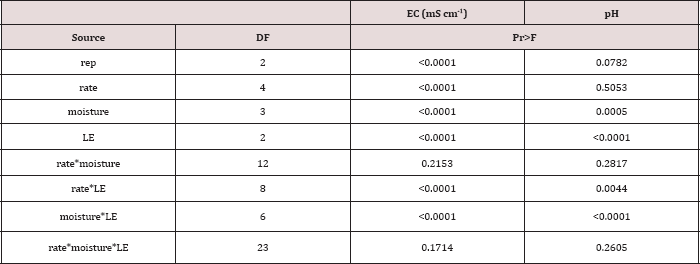

Leachate electrical conductivity and pH

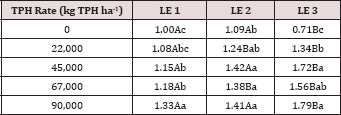

The main effects of TPH application rate, moisture regime, and

leaching event on leachate EC, and interactions between variables are

shown in Table 16. The two-way interaction of TPH rate by leaching event

was significant (P ≤ 0.05) for leachate EC (mS cm-1) and is

shown in greater detail in Table 17. A significant increase in leachate

EC is observed with increasing TPH application rates for each leaching

event. As TPH rate increased, the total amount of salts applied from the

OBM (Table 2) was greater, which led to higher leachate EC values as

the salts dissolved with the leaching water? A general trend of

increasing leachate EC with leaching event was observed for each TPH

application rate except for the control which received no amendment. The

leachate EC can serve as an indicator of the mobility of soluble

species in the solution and can be used to indicate the leaching front

for soluble species. Due to the fact that leachate EC continues to

increase at each leaching event while BTEX concentrations do not (Table

11), this confirms that the BTEX has either degraded or sorbed to the

soil or was lost via volatilization (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mean remaining total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH)

concentrations in oil-base mud (mg kg-1 OBM) for the BTEX leaching

study. OBM loading rates were applied at 90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000,

and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The treatments were subjected to four

different moisture regimes. OBM was sampled at 0, 7, 30, 60, and 91 days

after application. Remaining TPH concentrations are shown for each TPH

application rate, and sampling time, and are averaged over moisture

regime.

Table 16: ANOVA results for leachate electrical conductivity (EC; mS cm-1) and pH for the BTEX leaching column study. Results were significant when (Pr ≤ 0.05). LE = "leaching event".

Table 17: Mean leachate electrical conductivity (EC; mS cm-1)

averaged across moisture regime comparing total petroleum hydrocarbon

(TPH) application rates and leaching events (LE). OBM loading rates were

applied at 90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1.

The treatments were subjected to four different moisture regimes which

had one leaching event per month. Uppercase letters represent mean

separation of leachate EC (mS cm-1) between leaching events

at each TPH application rate. Lowercase letters represent mean

separation between TPH application rates at each leaching event.

Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

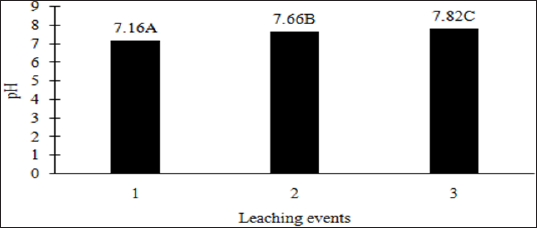

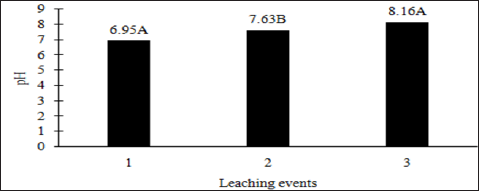

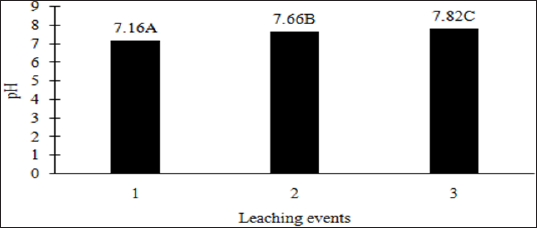

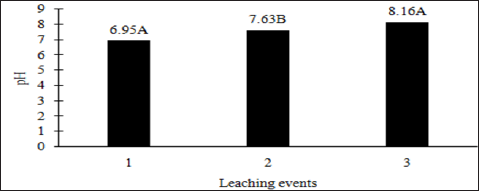

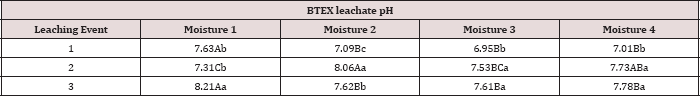

The main effects of moisture regime and leaching events, and the

interactions of TPH rate*leaching event and moisture regimes*leaching

events were significant at a = 0.05 for the pH of the leachate. Table 16

provides a complete list of ANOVA results for all main effects and

interactions for leachate pH. The main effect of leaching event was

significant (P ≤ 0.05) for leachate pH and is shown in more detail in

Figure 3. There were significant increases in leachate pH with each

additional leaching event. However, TPH application rate had no effect

on leachate pH because the pH of the control leachate also had

significant increases in pH with each additional leaching event (Figure

4). The increase in leachate pH across the leaching events was likely

due to the alkaline pH (8.23) of the water that was used to leach the

soil columns. As time progressed throughout leaching events, the

leachate pH approached the higher pH values of the water that was used

to leach the soil columns(Table 18).

Figure 3: Mean leachate pH comparing each leaching event for

the BTEX leaching column study. OBM loading rates were applied at

90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The

treatments were subjected to four different moisture regimes which had

one leaching event per month. Leachate pH values are averaged over total

petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) rate and moisture regimes. Uppercase

letters represent mean separation of leachate pH between leaching

events. Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

Figure 4: Mean leachate pH of the control (no OBM) comparing

each leaching event for the BTEX leachate column study. OBM loading

rates were applied at 90,000, 67,000, 45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg

TPH ha-1. The treatments were subjected to four different moisture

regimes which had one leaching event per month. Leachate pH was averaged

over moisture regimes. Uppercase letters represent mean separation of

leachate pH between leaching events. Statistical decisions were made at P

= 0.05.

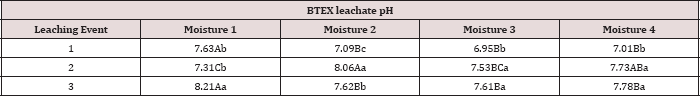

Table 18: Mean leachate pH values averaged over total

petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) rate, comparing moisture regimes and

leaching events. OBM loading rates were applied at 90,000, 67,000,

45,000, 22,000, and 0 (control) kg TPH ha-1. The treatments

were subjected to four different moisture regimes which had one leaching

event per month. Uppercase letters represent mean separation of

leachate pH between moisture regimes at each leaching event. Lowercase

letters represent mean separation of leachate pH between leaching events

at each moisture regime. Statistical decisions were made at P = 0.05.

Summary and Implications

The OBM was applied in this study at rates much greater than what is

allowed by current OCC regulations, and were not incorporated in order

to examine the worst-case scenario regarding environmental impact. The

OBM used in this soil column leachate study did not possess heavy metal

concentrations beyond normal soil concentrations. Benzene concentrations

in the raw OBM (2.65 mg kg-1) were higher than the EPA threshold limits established for inhalation (0.8 mg kg-1) and leaching to groundwater (0.03 mg kg -1).

Regardless, by day 7, the BTEX concentration in the mud had decreased

by 88% and benzene only leached out during the first leaching event

which produced benzene concentrations that were acceptable according to

USEPA drinking water standards. This was surprising due to the high

benzene content in the OBM, which greatly exceeded USEPA risk levels for

groundwater leaching, the short column length, and high hydraulic

conductivity of the soil utilized. An explanation for this is found in

closer examination of the assumptions made in creation of the USEPA

concentration thresholds for leaching to groundwater i.e. the assumption

that there is no degradation of benzene and that the entire soil

profile contains benzene from the surface to the groundwater interface.

As expected, increased OBM application rates resulted in higher leachate

benzene concentrations.

All leachate BTEX concentrations were below drinking water

thresholds. No trace metals were detected in leachate. Part of the

reason for non-detectable BTEX concentrations in leachate after the

initial leaching event on day 0, was due to 88% degradation of BTEX in

the applied OBM by day 7. Based on the results of this study, there is

little risk of BTEX leaching to ground water through land application of

OBM. However, it is unknown if this lack of BTEX movement was due to

extreme soil sorption, degradation, or volatilization. The main effect

of TPH application rate had the greatest effect on TPH degradation, BTEX

concentrations in the OBM, leachate BTEX concentrations and loads, and

leachate EC. As the rate of TPH increased, a decrease in hydrocarbon

degradation was observed due to the higher OBM to soil ratio that

limited oxygen inflow and microbial degradation. A plateau effect on

biodegradation of TPH was seen at day 60 and continued throughout day

91. At that point, we hypothesize that the microorganisms had likely

consumed all of the nutrients and could no longer biodegrade the TPH.

Therefore, applying a source of fertilizer and increasing the surface

area to volume ratio of the OBM via disking or using a bulking agent is

important when considering microbial degradation of TPH. During the

study, the maximum TPH degradation that occurred was 35%, which occurred

from the lowest TPH application rate. Leachate EC increased as TPH rate

increased due to higher loads of soluble salts. Leachate EC also

increased at each leaching event as opposed to the decreasing BTEX

concentrations with additional leaching event, which confirmed that the

BTEX had volatilized, sorbed to the soil, or degraded. The main effect

of TPH rate had no effect on leachate pH. Further studies should be

conducted in order to quantify BTEX volatilization that may occur with

land application of OBM, and deter mine if there is any possible human

health risks associated with any potential volatilization.

Read More About Lupine Publishers Journal of Oceanography and Petrochemical Sciences Please Click on Below Link:

https://oceanography-lupine-publishers.blogspot.com/