The profile of Addis Ababa city has been changing due to the

promotion of privatization, slum area clearance, construction of

condominium houses, and conversion of agricultural fields in the suburbs

to urban lands. Hundreds of low-income households have

been displaced and, as an aftermath, were adversely affected by this

development-induced displacement. The objective of this study

was to describe and explore the perceived social and psychological

effects of the “development-induced displacement” on a sample

of Twenty-three purposefully selected participants in Addis Ababa. Data

were collected from those low-income households who

were originally residing in Kebele houses around Tikur Anbessa Hospital

and later resettled into one of the suburbs of Addis Ababa

called “Jemo Three Condominium site” through open-ended interviews and

questionnaire. As expected, findings have indicated

that displacing people from the inner city to new resettlement sites in

the outskirts was associated with social breakdowns (such

as frustration to form close relationship with neighbors and absence of

warm and trusting relationship) as well as psychological

problems (like lack of confidence and motivation to earn a living and

poor self-esteem). The finding also indicated that the

displacement has additionally created loss of jobs, incurred high

transport costs, and challenged access to education and healthcare.

The damage caused by resettlement on poor resettles far outweighs its

benefits and, therefore, the government needs to revisit its

housing strategy.

Keywords: Displacement; Resettlement; Social wellbeing; Psychological Wellbeing

Introduction

Internally Displaced People are among the least studied

categories of people in the world and, hence, internationally

agreed upon definitions for it is yet to come. Developmentinduced

displaced persons are among the internally displaced

group. Scholars, therefore, used the operational definition for

‘Development-Induced-Displaced people as ‘persons or groups

of persons who are forced to leave their lands or homes or their

possessions as a result of development processes that put their

livelihoods in danger Pankhurst & Piguet [1], UN and Habitat [2].

The number of Internally Displaced People seems to be increasing

globally as about ten million people enter the cycle of forced

displacement and relocation on an annual basis mostly due to

development projects. Out of these, urban development projects

reportedly cause the displacement of some six million people every

year from their lands and homes Cernea [3], Pankhurst & Piguet [1].

It is widely and increasingly accepted that urbanization is inevitable

phenomenon. In developed countries like Europe and North

America urbanization has been a consequence of industrialization

and has been associated with economic development. In the

developing countries of Latin America, Africa and Asia, urbanization

has occurred as a result of high natural urban population increase

and massive rural-to-urban migration Brian [4], Minwuyelet

[5]. According to Cernea [6], ongoing industrialization and

urbanization processes are likely to increase, rather than reduced.

As the demands of the urbanizing population increases, notably

in Africa and Asia, it is inevitable that the need for infrastructure

development will grow enormously and displacement from inner

cities is likely to occur on massive scale McDowell [7], Pankhurst

& Piguet [1], World Bank [8]. Development-Induced-Displacement

has serious human rights and socio-economic impacts. It breaks

up entire communities and families, making it difficult for them

to cope with the uncertainty of resettlement. Risks are usually

higher for vulnerable groups, such as children, women, poor, the

elderly, ethnic minorities, and indigenous people Minyahil [9]. Furthermore, Cernea [10] has identified and discussed in detail

eight principal risks that lead to the impoverishment of displaced

community. These are: landlessness, joblessness, homelessness,

marginalization, food insecurity, increased morbidity, loss of access

to common property, and community disarticulation. Both global

and national experiences show that resettlement usually fails to

achieve its objectives UN-Habitat [11].

It is usually unproductive, ineffective, catastrophic, grievous,

and environmentally detrimental. As discussed by “…resettlement

often leads to impoverishment…and sometimes involves abuse

of human rights”. According to Pankhurst and Piguet [1], many

development programs are often in conflict with the interests of

local people worldwide. A number of communities have witnessed

serious resource depletion and economic impoverishment as

a result of their displacement in the name of ‘development’.

Feleke [12], Feyera [13], Eyasu [14], Eyob [15] examined the

consequences of urban development projects on the lives of

people who are evicted from their rural lands and houses. These

studies uncovered that, as a result of inadequate consultation and

compensation the displaced families are exposed to social and

economic impoverishment. The works of Gebre [16], Mengistu

[17], Wolde-Selassie [18] vividly depict the absolute failure, harsh

and ruinous life experience of resettlers in Ethiopia over previous

decades. Gebre [19] has discussed the issue in his report of urban

development and displacement in Addis Ababa. He outlined the

impact of resettlement projects on low-income households. His

research revealed that because of their relocation away from the

inner city, most of the displacees experienced different hardships,

such as decline/loss of income, poor access of educational and

health services, transport problems and breakdown of social

networks. Why does resettlement so often go wrong, and end up

leaving the resettled people (and often others as well) economically,

socially and psychologically worse-off than before? According to

Pankhurst and Piguet [1], there seem to be two broad approaches

to answering this question: the inadequate inputs approach and

the inherent complexity approach. Among these approaches

the inadequate inputs approach is evident in the process of

Development- Induced Displacement so far conducted in Ethiopia.

According to this approach, resettlement goes wrong, principally

because of a lack of proper inputs such as legal frameworks and

policies, political will, funding, pre-resettlement surveys, planning

the displacement ahead, consultation with those to be displaced,

careful implementation, and monitoring.

In Ethiopia, urban development appears to be the order of

the day and will remain an on- going process for decades to come.

There are indications that more new projects and the expansion

of existing ones will displace more people. In a televised press

conference in the context of the Ethiopian Millennium celebration,

the late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi indicated that 70 percent of

the houses in Addis Ababa would be demolished and rebuilt. An

inadequate master plan, poor housing facilities, environmental

problems, and shanty corners, among others, characterize urban

centers of developing countries Dierig, [20], Kamete, Tostensen,

Tvedten[21], Meheret [22], Potts [23], Rabinovitch [24]. The renewal

and development programs of urban areas often target slums

and shanty areas normally inhabited by low-income households.

Compared to suburbs, income generating opportunities and social

services are often concentrated in such areas. Therefore, relocation

of low-income households from inner cities to the outskirts would,

undoubtedly, affect their livelihoods and informal networks of

mutual assistance, their critical coping strategies Lourenço Lindel

[25]. It has been widely agreed that people dislocated from inner

cities are likely to lose important locational advantages linked to

their survival Davidson et al. [26], Gebre [19]. Addis Ababa is in a

position that it is not able to accommodate inhabitants due to the

substantial flooding of new comers from rural areas and small

towns of the country in search of better life. Nevertheless, they

usually find themselves in difficult socio-economic circumstances.

The number of homeless and those who live in very poor houses is

increasing in an alarming rate Gebre [19]. According to a report of

80 per cent of the population in Addis Ababa lives in sub-standard

slum housing that needs either complete replacement or significant

upgrading. There is a massive demand for serviced, healthy, and

affordable housing in the capital. This demand stems both from

the current housing deficit and the poor quality of the existing

government housing stock (kebele houses) that are beyond repair.

The government of Ethiopia estimates that the housing deficit in

urban areas is between 900,000 and 1,000,000 units, of which

300,000 units are found in the capital city, Addis Ababa MWUD [27],

UN-Habitat [2]. The government also estimates that only 30 per

cent of the housing stock is in a fair condition, while the remaining

70 per cent is in need of total replacement.

In response to this challenge, the Ethiopian government

outlined an ambitious vision of constructing condominium houses

for low and middle-income households and inner-city up grading

program since 2005 UN-Habitat [2]. The initial goal of the program,

Integrated Housing Development Program (IHDP), was to promote

homeownership for low and middle-income households by

constructing 400,000 condominium units, reduce unemployment,

promote the development of 10,000 micros and small enterprises,

enhance the capacity of the construction sector, and regenerate

inner-city slum areas. For the purpose of achieving these goals the

Addis Ababa city government displaced and displacing many lowincome

households from inner city to peripheries of the city. The city

is expanding horizontally, and the population is moving to unplanned

settlements on the peripheries at the expense of agricultural lands.

Since most private investments are highly concentrated around

the main urban center, the problem of displacement is becoming a

primary concern Hehl & Stollman [28]. Addis Ababa, the capital of

Ethiopia, is undergoing a major transformation as evidenced by the

construction of condominiums, road, networks, schools, healthcare

institutions, hotels, real estates, banks, shopping centers, and many

other businesses. There is a sense of jubilation on the part

of authorities and the general public with the direction of the

urban development policy and the remarkable gains scored thus

far. What remains unnoticed, however, is that thousands of people

have been displaced and adversely affected by the process of urban

development Teshome [29]. The process of relocating people from

inner city to new resettlement sites in the outskirts have disrupted

the relocatees’ business ties with customers, broken their informal

networks, caused loss of locational advantages, loss of jobs and

incurred high transport costs Gebre [19]. Although the Addis Ababa

city administration considers that its land lease allocation system

boosts the market value and proper exploitation of urban land,

most of its projects are not in accordance with the international

and national policies and the norms set by agencies like the UN, the

World Bank and the Environmental Protection Authority. The rural

people affected by the urban projects are also not actively involved

in the assessment, feasibility studies, planning and implementation

process. The urban development projects rather have tended to give

more attention to local and foreign investors than the urban poor

and the peasants who live in the vicinity of the city Melaku [30],

Pankhurst & Piguet [1]. Many other studies focused on the physical

and economic impacts of relocation scheme giving emphasis to

the housing conditions and the availability of infrastructures.

These studies gave little, if any, attention to psychological and

social breakdowns that result from displacement. But the present

study focused mainly on social breakdowns and psychological

disturbances associated with low-income households who were

displaced from inner city (around Tikur Anbessa) and located to

Jemo Three condominium site which is found in the outskirts (13

kilometers away from the center of the city). This area (Jemo Three)

was part of Oromiya region previously. This study focused on lowincome

households who were living in Kebele houses paying few

birr for house rent (8.6 birr on average per month). People who live

in Kebele houses are believed or expected to be relatively poor, and

hence, adaptation to new environments would be difficult for them

when compared to people who are financially strong.

The available statistics reveal that social services and

infrastructural facilities are concentrated in the inner city as

compared to suburbs Eyob [15], Gebre [19], Nebiyu [31]. Therefore,

relocation of people from the center of a city to the outskirts

would lead to social and psychological impoverishment as well as

to the decline of access to infrastructural services and facilities.

The aim of this study is to explore the aforementioned problems

of displacement and to indicate sound strategies to minimize the

adverse effects of Development-Induced-Displacement. If the

expansion of urban areas and clearing shanty corners continue

the same way in Addis Ababa, as expected to be the case, one can

imagine that large number of people to be displaced will soon face

social and psychological problems. Therefore, research that assesses

the social and psychological consequences of urban development

projects is expected to play an important role in filling the existing

knowledge gap. Therefore, this research is conducted to examine

the multifarious effects of development-induced displacement

focusing mainly on infrastructural problems, livelihood impacts,

social problems, and undesirable psychological effects.

Methods

Research Setting: this research is conducted in one of the

condominium sites found in Nifas Silk-Lafto sub-city of Addis

Ababa named as Jemo Three condominium site. Addis Ababa is

the economic and political city of Ethiopia, and the melting pot of

different nations and nationalities. Almost all the Ethiopian ethnic

groups are represented in Addis Ababa due to its position as capital

of the country and its location in the geographic center of the

country (PEFA, 2008). The city has a population of more than 3.5

million, ten times larger than the second largest city in the country,

Dire Dawa. In the past couple of decades Addis Ababa has risen from

a city of self-built single-store homes, to a city of skyscrapers. This

happened as a result of the inauguration of the Integrated Housing

Development Program (IHDP) in 2004. The IHDP is targeted at

constructing condominium houses for low income groups through

cleaning shanty corners. While the IHDP has the laudable aim of

targeting the low-income sector of the population, unfortunately

experiences have shown that many poor people are not benefiting

from the IHDP due to inability to afford the initial down-payment

and monthly service payments. The poorest are primarily excluded

from securing a unit because they do not have the financial capacity

to pay the required down-payment. Furthermore, the inability

to pay the monthly mortgage and service payments forces many

households to move out of their unit and rent it out rather than

risk losing it through bank foreclosure. The IHDP aims at producing

low-cost houses but not low-quality houses. Nevertheless, there

have been reports of burst sewerage pipes that leaked through

all floors and wide-spread cracking of wall plaster. The expected

lifespan of the units is 100 years, although local professionals and

residents doubt the validity of these predictions. Construction

quality is affected by micro and small enterprises seeking to make

additional profit by using cheaper substandard fixtures, such as

doors and door handles, as well as the low levels of construction

skills and capacity, which is somewhat understandable considering

the vast numbers of recently employed inexperienced contractors

and builders necessary for projects of this scale. As mentioned

earlier the setting of this research is Jemo Three condominium site.

The research site is found at the western part of Nifas Silk-Lafto

sub-city. Jemo Three is 13 kilometers away from the center of Addis

Ababa (Piassa-Georgis). This area was previously governed by

Oromiya regional state. Some of the peasants living in the area were

displaced and relocated to another area while the rest were given

money as a compensation for their land. It is witnessed by people

who were living in this area that the land was fertile. Peasants

were producing crops like barley and wheat. The peasants were

displaced without their willing. It is to this area that people who

were living in inner city (around Tikur Anbessa Hospiital) were

relocated. Even though peasants were producing sufficient amount

of crops from this site, it is not suitable for people who were living

in inner city and relocated here. The majority of displaced people

were earning a living by getting employed in government and

nongovernment

organizations in inner city. Jemo Three is characterized

by relatively poor social services such as transportation, health care

and schooling.

Population and Participants: low-income households who

were displaced from Tikur Anbessa area and resettled to Jemo Three

are the population of this study. These households were living in

kebele houses owned by the government before the displacement

where they pay very amount of money for house rent. The quality

of kebele housing stock is low: typically constructed of mud, wood,

and/or discarded materials. Kebele houses are old, having been

constructed many decades ago and little to no maintenance has

been carried out. Some houses remain with no access to water

and electricity, and many do not maintain minimum standards

of sanitation. Nevertheless, the social and cultural bonds in their

previous village were stronger. They had stronger relationship

with people around them. Furthermore, they were economically

advantageous before displacement because they were living in

inner city where economic activities were better. They lived in this

area for more than twenty years on average. Now they are living in

condominiums where they were paying 875 birr for house rent on

average per month. Data were collected from 23 households who

were selected based on snow ball sampling technique. Snowball

sampling technique was used since the researcher knows two

households who were dislocated from Tikur Anbessa area and

relocated to Jemo Three. The process of data collection was started

from these two information-rich resettlers. Then, they were asked

to locate those households who were displaced from the same area

and relocated to Jemo Three.

Tools of Data Collection and Analysis:

Questionnaire: Since this research was mainly qualitative

in nature, open-ended questionnaire was developed by the

researchers by relying on the existing literature. The purpose of the

questionnaire was to assess the psychological and social impacts

of displacement on low income households. It was also intended

to compare the difference in infrastructure before and after

displacement. The questionnaire had two parts. The first part dealt

with demographic variables such as age of the respondents and

amount of money paid for house rent before and after displacement

while the second part, which was comprised of 7 items, assessed

the quality of the respondent’s social (e.g., “Do you think that your

relationship with your neighbors is warm and trusting?”) and

psychological life (e.g., “Are you satisfied/dissatisfied with your

current setting?”) including the quality of infrastructure. Initially,

the questionnaire was written in English and then translated into

Amharic and it was the Amharic version that was administered

finally.

Interview: the interview guide consisting open-ended

questions was primarily written by the researchers was translated

into Amharic language by the help of two language teachers in Addis

Ababa University. This guide was composed of 9 items assessing the

social life (e.g., “Does displacement affect your life? If yes, in what

ways?”), psychological life (e.g., “Do you think that displacement

affected your self-concept and motivation? If yes, explain how?”),

and infrastructural quality (e.g., “Where do you get better access

to social services like road, electricity, telephone, transportation,

shopping centers, clinic, etc.?”) of respondents who were displaced

from inner city, due to development-induced displacement, and

relocated to the peripheral of the city, specifically to Jemo Three.

Data Analysis: data were collected through interviews and

open-ended questionnaires. The data were organized in to different

themes and analyzed thematically. Using different methods,

informants’ sayings were highlighted whenever they have relevance

with the topic of the study. Codes were created and brought together

for categorizing purposes. Finally, the main themes (based on the

category) were identified and the categories were brought together

and rearranged under those themes.

Ethical Considerations: During the process of data collection,

all necessary precautions were made to ensure that the rights of

the sources of data were respected. The data collection instruments

were accompanied by informed consent form. The research

participants were debriefed concerning the purpose of the research.

Besides, the research participants were informed that participation

in the research is on voluntary basis and they have all the rights to

pull out if they find the data collection or the nature of information

is not consistent with their expectations.

Findings

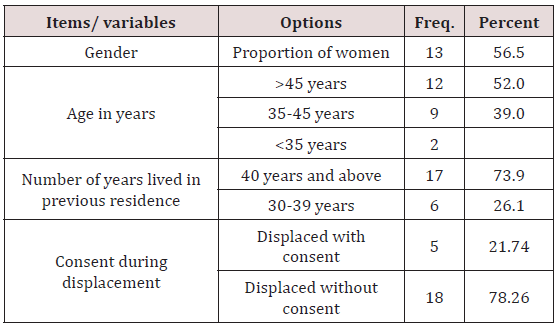

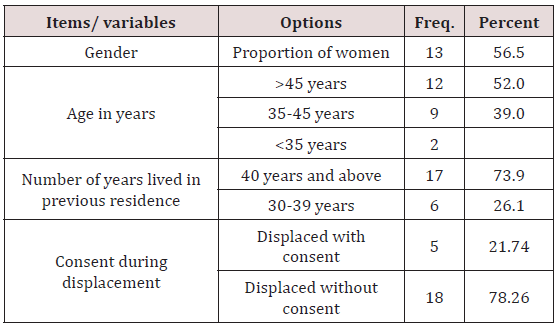

Characteristics of the Respondents: there were more than

sixty households that were displaced from their previous residence

and resettled into Jemo Three Condominium site. As indicated

in Table 1, data were collected from 23 participants from lowincome

households of which 56.5% were females, 91 % were aged

more than 34 years, and almost all of them have lived for more

than 30 years in their previous residence. More importantly, the

greater majority (78%) have expressed that they were displaced

without consent. Interview results also confirm this observation.

For example, a 64 years old woman expressed this discontent as

follows:

Table 1: Characteristics of the respondents.

Unless forced, nobody wants to get detached from his/

her home where he/she has lived for many years. Nobody wants to

leave a home we have been grown up, learnt, and passed through

huge life experiences… (A woman interviewee No. 6, age 64).

A 51-years-old woman interviewee also expressed, “…if

you ask me how I left my old and lovely home, I will definitely tell

you that I was forced by groups of youngsters who were given the

task of destroying shanty corners (our old homes). They used to

threaten us frequently to move to this new site as soon as possible.”

A response obtained from another male interviewee aged

61 years also illustrates the same idea. “We were not happy by

getting separated from our previous homes, though the aim of the

government was development”.

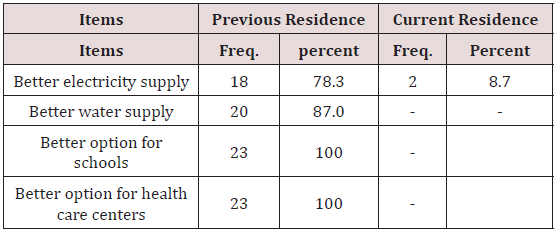

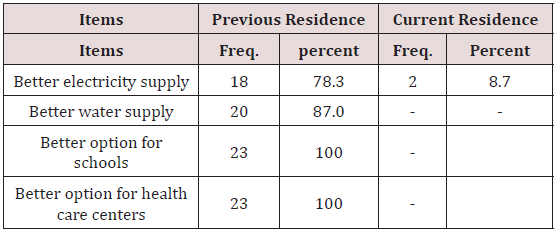

Infrastructural Concerns: Data obtained from the research

participants of the study clearly showed that there were noticeable

differences in availability of regular and adequate services of

electricity and water before resettlement (at participant’s previous

residences) and after resettlement (at participant’s current

residences, Jemo Three). For example, an interviewee said, “there

is slight difference in my previous and current residences, but

concerning water supply the two areas are incomparable. At Jemo

Three, we get water two or three days a week. We get water at

mid night, if you are able to wake up at about 12:00PM or 1:00AM

o’clock” (male, age 51). Another relatively younger interviewee

(Female, aged 36 years) responded as follows:

…there are huge differences between electricity and water

services in my previous and current houses. I wash my cloths

once or twice in one month here (new residence) due to shortage

of water, but I usually wash once every week at Tikur anbessa

(previous village). I learnt how much water is important in once life

in practice (though I know it theoretically) at Jemo Three. I started

to use water very economically. If I fail not to use economically I

must collect water in bucket from very far area and carry the bucket

up on to the third floor. The supply of electricity is relatively better

than that of water supply at Jemo Three, although, it is worse when

compared to the supply of electricity at Tikur anbessa. Here, electric

power disappears once or twice a day.

Table 2: perceived infrastructural services of participants before

and after displacement.

Similarly, responses obtained from the questionnaire revealed

that there were better electricity and water supply in their previous

than current residences. Among the 23 respondents who filled

in the questionnaire, three of them responded that the supply of

electricity and water in their previous and current residences was

similar. The responses of the rest 20 participants are given in Table

2. As indicated in Table 2, nearly all respondents were saying that

their previous residence was better in electricity supply (78.3%),

water supply (87 %), options for their children’s schools (100%),

and health care centers (100%).

Interviewees were also complaining about the distance

of the site from the center of the city, which incurs them extra

transportation cost:

My previous living site was found at the center of Addis Ababa.

I was surrounded by Merkato, Legehar, Piassa, Mexico, Abinet,

Autobus tera (bus station), etc. Look at those beautiful areas. You

can get everything you need in your life (clothes, food items, goods)

simply by moving towards these locations with very few amounts

of money, or you can even go on foot. Now, I have to, at least, pay

more than 20 birr to go to Merkato. I should have to go to the center

of the city, Mexico for instance, to buy things I need because goods

and food items are relatively more expensive here when compared

to their cost at the inner city. Furthermore, things you need are not

sufficiently found here (male, age 61).

Another interviewee explained the distance of Jemo Three from

the center of the city and problems associated with transportation

as follows: My neighbors who were displaced like me were resettled

to better sites. I am not lucky by having thrown to this site. It is

too far from inner city and the environment is ugly. I think you too

agree with my idea. Isn’t it? I will never like this site because it will

never get improved or will take very long period of time. I have to

leave my home very early in the morning, like about 11:30 - 12:00

o’clock due to the reason that he road from the center of the city to

my house usually gets overcrowded. Likewise, I need to stop my job

early in the afternoon, for instance at about 10:30 so that I could get

back to my house before the road once again get congested. What

bothers me is not only about the congestion of the road but also

about the extra amount of money I am asked on a taxi. We are asked

to pay more than the limit set by the transport authority” (male,

age 50 years).

Finally, the data collected concerning the provision of schools

and health care centers at respondent’s previous and current

residences revealed that there was significant difference in the

number and quality of schools and health care centers. The data

showed that respondents were surrounded by various health care

centers and hospitals in their previous residences. They were

receiving medical services at different government health care

centers (Tikur Anbessa hospital, Zewditu hospital, Teklehaimanot

health center), but today, in their new village, there is only one

government health center. This was substantiated by the following

quote. “Recently, I started to frequently pray to God not to get me

sick. You know why? Last time (she attempted to recall the exact

time, but she couldn’t) I went to wereda 02 health care center (a

health center around Jemo 1) with one of my neighbor. We went there because she was sick. The long queue of patients I observed

on that day made me pray to God to stay me healthy. There are many

clinics for those who are rich. These clinics are not affordable by

poor people like me and my neighbor.” Data about the availability

of schools for children of displaced parents showed that parents

were experiencing shortage of schools for their children. “In my

previous village I can send my children to different schools because

we had various options. The schools were also relatively closer to

our homes. Here we have very limited options and simultaneously

the few available schools are located at distant areas” (Interviewee

No. 11, male, age 56). The other interviewee (male, age 49) also

reported that there was shortage of schools and parents were

suffering a lot. “…of course, the schools found in our area are meant

for rich people because they charge you a lot of money. We cannot

send our children to these schools. Affordable schools are found

a bit far from Jemo Three.” The researcher of this study observed

that the schools found around the study area were not intended for

those poor displaced people. These schools were charging not less

than 600 birr per month for a child. The researcher also noticed

that some parents were sending their children to schools that are

found in their previous village. These parents had to wake up and

force their children wake up very early in the morning so that they

could send their children to schools before the roads get crowded.

Responses obtained from questionnaire similarly showed that there

was a difference in the number of health care centers and schools

for children of displaced parents. Resettlers were asked to compare

where they found relatively better health care centers and schools

for their children. Those participants who had no children to send

to school were asked simply to compare the number of schools in

their old and current living areas.

According to the observation of the researcher, the presence of

two churches (St Gebriel and St Mary) at Jemo Three condominium

site was the only thing that made Christian respondents feel

good and a little bit happier. There was no worshipping area for

Muslims at Jemo Three, but there is a mosque around Jemo Two Site

which is not too far. Concerning worshipping areas, respondents

were comfortable, though, there were differences in the number

of churches and mosques between the previous and current

residences of resettlers. “We (Christians) have two churches both of

which are very close to our homes. St Gebriel Church is at the back of

my home.” The other participant explained about worshipping area

in her site as “Even though, I don’t want to compare the number of

churches and mosques, there is no single mosque at which we pray

at least one prayer a day, leave-alone five prayers. There were not

less than 5 mosques around Tikur Anbessa” (Christian and Muslim

women interviewees of age 41 and 48 respectively).

Livelihood Impacts: Responses obtained from the interview

indicated that poor people who were displaced have many concerns:

“I am one of those whose life is messed up as a result of

Development-Induced-Displacement. I am unable to deal with

the required monthly mortgage repayment. Due to this reason, I’m forced to beg and pay the monthly cost of my house not to

lose it through foreclosure by commercial bank of Ethiopia”

(agd 55 years).

“The lives of many poor and those who were unable

to cope up with the ever-changing condition of life are being

affected as a result of displacement from their village and

being resettled to the outskirts of the city. I and many others

are unable to meet our needs. My life has been affected because

my home cannot accommodate my previous income generation

activity. Previously I bake bread and injera for sale. The lack

of my previous income source put me under extra financial

pressure. No schools around for our children and there are

insufficient employment opportunities for youngsters when

compared to our previous site” (aged 56 years).

Many of the respondents were earning a living from selling

different goods, for instance, charcoal, vegetables and fruits such as

tomato, potato, onion, etc. in their previous village. They were buying

these fruits and vegetables from Piassa-atkilt tera with very cheap

price. Atkilt tera was very close to their previous residence. It was

not more than 2.5 kilometers for which they were being charged less

than two birr for a taxi. But unfortunately, they are located far from

the inner city, as a result of Development-Induced-Displacement

where different goods for consumption and infrastructural services

were not easily and closely available. Atkilt tera is very far from

Jemo Three (more than fifteen kilometers). It costs them above ten

birr (huge money, if their poverty is considered) to arrive at Atkilt

tera with taxi. In addition to its distance there was no sufficient

transportation system and it was an area where taxi drivers

frequently violet the rules/tariff set by transport authority. They

usually got charged above the tariff. Due to this and other similar

factors, the overwhelming majority of respondents indicated that

their income is significantly declining. As a result, respondents were

encountering economic and psychological problems as mentioned

by one of the informants:

My previous house was closer to church, and market

places. I just go to Markato and Atkilt tera, buy onion and

tomato with Birr 20.00, display it in front of my house and then

sell it and make a profit. But, our present location is detached

everything; what can you work and earn in this wilderness

environment. Rich men may establish a business but poor

people like me are getting hard time. You should wake up early

in the morning to take a bus to Markato; taxi is even hard to

think about (43 years old interviewee No 23).

Furthermore, respondents indicated that the cost of

their new houses was another factor that exacerbated their

poverty. They were asked to pay between Birr 20,000.00 up

to 40,000.00, depending on the number of bedrooms, to take

their new houses. As already mentioned above, almost all of the

participants of this study were poor and had no reliable daily/

monthly income. Some of them had paid the initial payment

(20% of the total cost of the house) by begging from religious

institutions while some others paid by asking from their

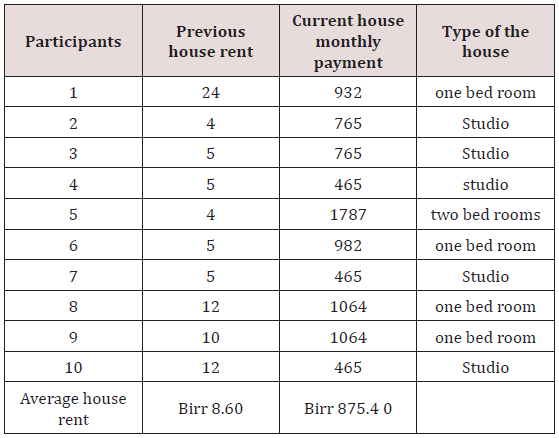

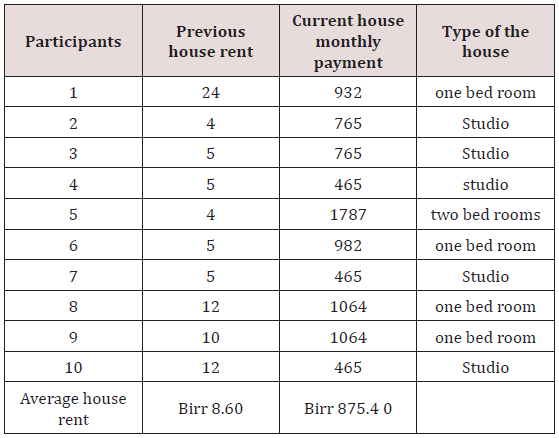

relatives. The six interviewees in Table 3 explained this issue

as: “I and my neighbor, Weizero Zeynaba, were forced to move

from one church/mosque to another to collect the money that

was required for the initial payment (18,000 and 27,000 birr

respectively). Finally, both of us managed to collect sufficient

amount of money for the 20% down payment.”

Table 3: Housing payment of participants before and after

displacement.

Though the initial 20% was paid, the participants were worried

and challenged with the amount of money to be paid monthly

for twenty years to reimburse the remaining 80% of the cost of

their houses along with the interest. As it can be referred to in

Table 3, they were paying very small amount of money for house

rent before displacement (about Birr 8.60). After displacement

they owned a house but were asked to pay nearly 100 times per

month (i.e. an average of Birr 875.4 0. This dramatic increase in

expenses has occurred in the face of a decline in income and rising

standards of living in Addis Ababa. Because of these challenges,

many condominium owners were forced either to sell their house

or rent it and then live in a house with lower rent so that they can

make a living with the difference earned. The other lesson taken

from this research was the inability of some respondents to adjust

to the life styles that are expected from someone who leaves on

apartment houses. The life style of people who were living in old

kebele houses made of wood and iron sheets were different from

those who live on large apartments. Some of these problems were

observed while they were slaughtering, traditional injera baking,

washing clothes, and boiling coffee. The life in apartments was

found in convenient to carry out these activities in a traditional way.

In the same way, the UN-Habitat (2011) reported that the building

designs of condominium houses in Addis Ababa do no respond to

occupants’ customary activities such as preparation of traditional

injera, bread, and slaughtering of animals. These activities require

sufficient space for large ovens and open areas. Due to lack of

sufficient space in the condominium units, the above-mentioned

activities were being undertaken in circulation areas, which caused

inconveniences for neighbors.

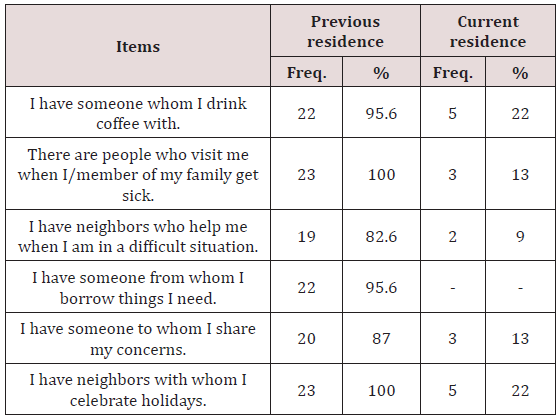

Social Wellbeing: The data collected concerning the number of

intimate neighbors, level of social security, and warm and trusting

relationship that displaced people experienced revealed that they

have found it difficult and frustrating to form close relationship

with others in their new residence when compared to their

residence before displacement. The data also showed that intimacy

with their previous neighbors was stronger than the current one. A

response from 38-year-old man which was taken from the interview

strengthens this idea. “There were so many people around me

when I was there (old residence) and I had reliable friends too.

All those my friends and others whom I know were resettled to

different condominium sites, though, it is not clear for me that the

benefit of dispersing people who have been living together apart.

I found it so difficult to form and maintain relationship with my

new neighbors. I think everybody is not happy to carry on his/her

life without having any relationship with neighbors.” Furthermore,

the way a man of age 49 responded clearly shows that those who

were resettled to Jemo Three area were unable to connect to people

around them. “I had smart link with those people around me in my

previous home. Our relationship was interesting. You Know that we

used to borrow and give goods and food items (even injera)? I can

leave my children with my neighbors so that they can take care of

them when I had to move out of Addis Ababa or when I was sick.

Doing this is totally impossible here. I don’t know what would likely

to happen in the future. I hope things will get better.”

In the same vein, resettlers had many people to talk to and

to listen at before resettlement than after resettlement. They had

many people alongside them to share their day-to-day concerns

before displacement. They have found very difficult to open

up when they want to talk to their new neighbors. The current

political instability in the country have made people stay away

from one another and exacerbated the loneliness of people living

in condominium houses. “I am a social animal. As a social animal I

have to get someone to whom I express my day to day concerns. I

need to have someone whom I trust. As you are observing I am very

old person (approximately above 70). All human beings need to

have good neighbors. For old and poor people like me the need will

be higher. Many of us have not yet established good relationship

with people around us” (4th interviewee, male). The following

quote which was taken from an interview conducted with a woman

interviewee of age 46 revealed that people who were displaced

from inner Addis Ababa and relocated to outer part of the city

were in an isolated life condition. Truly speaking, I and those who

are displaced from inner city are experiencing harsh and difficult

conditions in so many ways. For instance, I know only three persons

on this building (there are 30 homes on the building of which

11 were empty) and our relationship is not more than greeting

each other. I think it was ten days before that I heard someone

shouting and looking for help on our building. I wanted to get out

and help the person but I preferred to stay at my home. I did not know

whether that person received any help or not. This did not

happen in my previous residence. We know each other very well

and help one another. The condition of our life and the quality of

our relationship before and after displacement are incomparable.

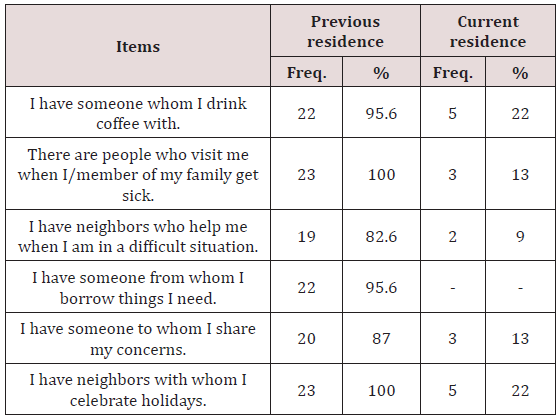

Responses obtained from questionnaire in Table 4 also indicated

that respondent’s relationship with neighbors before displacement

was sincere and trusting. The following table vividly depicts the

differences in the quality of the participant’s relationship at their

previous and current residence.

Table 4: Perceived social support of the participants before and

after displacement.

In relation to resettles participation in social roles such as idir,

ikub, and mahber; data showed that displaced people had better

and interesting participation in social activities in their previous

village than in the current residence. The majority of respondents

reported that they did not fit well with people around them. They

had no social partners at their current residence and hence have

poor participation in social activities taking place in their village.

I know nobody here. There is no interaction among people in this

village because everybody spends his/her time in his/her own

closed doors. There is no one I know to the south, north, east and

west of my home. I doubt if I could get someone who would bury

my body (male interviewee of age 48). In an interview conducted

with a 55-year-old male participant, social roles that link people

together such as idir,

ikub, and mahber, are absent in their new village.

“Although, it is our responsibility to form relationship with our new

neighbors and participate in various social roles, currently, we are

not in a position of doing this. This could be due to the fact that we

afraid one another so that nobody is willing to take the initiation.

I came to Jemo Three nine months before. There was one person

on that building (demonstrating the building) who was trying to

talk to us so that we could begin knowing and visiting each other.

Nevertheless, there is no idir and other social activities in this area.”

Furthermore, a relatively young participant explained the absence

of participation in various social activities. “In our previous village

we have so many reliable neighbors from different groups of

people. We have good relationship with Muslims, youths, elderly, employed, unemployed, and with other categories of people. If

someone needs help due to illness, poverty (of course all of us are

poor), and death of relatives we really spend our time, money, and

energy to help our neighbor who is in need. Wow! That was very

sensational. I think I will never and ever come across that type of

life here after. As you see here (in her new village), most of the doors

are closed and locked. Nobody is willing to visit his/her neighbors.

Our culture and religion encourage us to visit our neighbors and

strengthen our social relationship. I, sometimes, feel as I am not

living with Ethiopians as Ethiopians are good at social life. I think

this (poor social relationship) is the result of modernization” (a

woman interviewee No. 21, age 38). Responses obtained from

questionnaire in Table 5 revealed similar results. Participants who

were displaced as a result of development and resettled far from

the center of the city were not participating in social activities and

the presence of reliable individuals was poor as indicated in the

Table 5.

Table 5: social engagements of participants before and after

displacement.

Psychological Wellbeing: According to a response obtained

from an interviewee (Male, aged 61 years), “We were nothappy by

getting removed from our previous homes, though the aim of the

government was development. Here, there are no worshipping areas

(mosques), schools for our children, and so on. These were some of

the reasons that made us resist the displacement.” Data collected

revealed that respondents were not satisfied with the process of the

displacement and resettlement since it was conducted without their

consent. They were also dissatisfied with the new environment,

transportation costs, absence/shortage of worshiping areas, and

the likes. Furthermore, the new area requires new living condition.

The environment was not suitable for some typical life activities

of the respondents, for instance, slaughtering purpose, washing

clothes, and the likes. These factors led respondents to problems

of adaptation to the new environment. In fact, data revealed that

resettlers’ were more satisfied with their new homes than with

their previous old homes because the buildings were attractive and

eye catching than their previous old homes. The following quotes

were taken from the interviews conducted with three interviewees.

“Our earlier houses were very small in size and built of wood and

cardboard. Members of more than 5 houses were using a single

toilet in common so that we sometimes stand in a queue. My new

house has three rooms and I am using my own toilet alone. Don’t

try to compare those shanty houses with these beautiful buildings.” The

second interviewee responded: “Even though I love my house

I don’t like this area. The weather is too cold here.” Lastly, the third

interviewee replies as follows. “Of course, there is a huge difference

between my previous home and my new home. Home alone

cannot generate satisfaction. Satisfaction is obtained through the

combination of various things” (male and female interviewees No.

4, 14, & 23 respectively).

Responses obtained from questionnaires and interviews

indicated that many respondents’ effort to live a kind of life they

need was not successful after resettlement. Almost eighty percent

of the participants reported that they are losing confidence and

motivation in their struggle to live a better life. The following quote

clearly shows that some of the participants were losing interest

and motivation in their day-to-day life activities. “I was very strong

person. I wake up very early in the morning. But now, I do not want to

even get out of my bed. My interest to go to employment is declining

from time to time” (a man of 47 years). This kind of psychological

impact emanated from the feeling that they were displaced without

their consent and due to the fact that they were relocated to the

outskirt of a city. Data collected about loneliness and rejection

indicated that most of the respondents reported that they did not fit

well with the people and the community around them in their new

village. Resettlers did not feel attached to the people around them

after resettlement. “When I walk out of my home, after few strides,

there were many people who usually greet me and whom I greet,

but here (in her new house) I found no one to say ‘good morning/

good afternoon’ even after travelling remarkable distance” (woman

interviewee of age 39). A response obtained from an interview

held with another woman who was 44 fortifies that participants

were isolated from the community. “When I wake up from a sleep

I usually hear noise of children, neighbors, and noise from cars

(before resettlement). Here (after resettlement), you hear nothing.

Life in condominium houses is so difficult for me because nobody

is conscious of you. Nobody knows whether you are happy or

not; whether you are fine or not; whether you need help or not.”

Likewise, responses obtained from questionnaire revealed that

many of the respondents were experiencing the feeling of isolation

and that of rejection. Some of them felt that they were rejected from

the larger community. The aim of the questionnaire was to compare

the quality of psychological variables before and after displacement

as given in the table below. Equally speaking, many respondents

reported that their circle of friends and acquaintances were too

limited after displacement and hence they were experiencing a

feeling of loneliness. They have no confidants to share their social,

psychological and life issues. One of the male informants aged fiftysix

speaks out as: “We are thrown away as a dust as if we were not

created from mankind. I know not more than six individuals here.”

The other interviewee also strengthened the idea as follows: “It has

been ten days since I got a visit by someone in this new site. Nobody

knocked at my door these days. If I want to talk to someone I have

to go to other condominium sites where my previous neighbors

were relocated (people living in the same area were relocated to

different and far away sites after displacement) or I have to go to

my old village so that I would share my concerns and inner feelings”

(11th interviewee, male, age 56).

Data obtained from questionnaire about loneliness and lack

of confidants to share problems in life reveals similar results with

that obtained from interviews. Although, almost all respondents

reported that they were not suffering from loneliness before

displacement, 74 % of the respondents indicated that they were

experiencing a feeling of loneliness after displacement, while the

rest 26 % explained that they were in a feeling of companionship.

Concerning the availability of confidants to discuss problems with,

the data showed that 87 % of the displaced people indicated that

they had no one close to them to whom they share their concerns at

their new residences, though; the majority of them had confidants

at their previous residents. The other 13 % reported that they

had confidants both at their previous and current residents.

Respondents were also asked about the feeling of frustration and

hopelessness. Responses obtained from the interviews revealed

that people who were displaced from inner city and relocated to

remote areas were experiencing frustration, negative attitude

about themselves, as well as hopelessness. Here after I would have

no hope. Early in the morning I go to church and when I come

back to my home I spend the rest of the day sleeping. It is better

to die than to live in such a miserable condition (64 years old, male

interviewee, No.22). A woman interviewee of age 49 presented her

feeling as follows. “Previously (before displacement) we spend our

spare time with our neighbors because there were many people

around us. As you see here (demonstrating at the building on

which she is living) there are only six houses who are not reserved.

The other 24 houses are occupied by at least one household, i.e.

there are at least 24 individuals currently living on this building.

I have a relatively better relation with individuals living on these

two rooms (indicating at the two rooms beside her home on the

same floor). Therefore, I am not comfortable with this kind of life

style. To be honest with you, I am in a position to leave this area.

I will rent my home and scape out of this frustrating and hopeless

life. It is very recently that I learnt that our culture (collectivist

culture) is very important for our health and day-to-day activities.”

Correspondingly, another participant who was living on the same

building but different floor described his wellbeing as “I was a very

happy person when I was around kebele 44 (one of the kebeles

found in her previous village). The reason was that I was living a

relatively joyful life before I was forcefully displaced from my home

in which I lived for nearly 30 years. Although my previous home is

not comparable with this beautiful home (the previous home had

only one room and very old), it was my home in which I gave birth

for all my children. The lesson I learnt from my recent life is that, it

is not the beauty and quality of home that makes people satisfied

and happy; rather it is the quality of your relationship and your

mental state. I can’t adjust myself to this village forever” (53-yearold,

woman interviewee, No. 9). In the same vein, responses

obtained from the questionnaire revealed that the percentage of the participants’ feelings of hopelessness and frustration after

displacement was significantly higher when compared to their

feelings of frustration and hopelessness after displacement as

indicated in the table below.

Discussion

Forced displacement arises from the need to build infrastructure

for new industries, irrigation schemes, transportation highways,

power generation dams, or for urban developments such as

hospitals, schools, and airports. Such programs are indisputably

needed. They improve many people’s lives, provide employment, and

supply better services. But the involuntary displacements caused

by such programs also create major impositions on some segments

of the population. According to Cernea [10], displacement leads to

social disarticulation. If a community is displaced it tears apart the

existing social structures. “It breaks up families and communities;

it also dismantles patterns of social organization. From the findings

of this research, one can clearly observe that displacing people from

their habitual areas breaks up the social relationship and kin ties.

Many resettlers reported that their social networks have broken

down. Almost all respondents of this research reported that there

was significant difference in their social wellbeing before and after

displacement. They had satisfying connections with people around

them in their previous village. There number of people they usually

visit and visited by before displacement was relatively better. The

finding further indicated that the social relationship of displaced

people is weak not only in terms of the number of people they have

contact with but also in terms of closeness to people around them

in their new village. The participants made a point that they had no

close and trusting relationships with neighbors in the new village

(after displacement). Similarly, it was obtained from the finding

that participants did not have someone to talk to and to listen at.

The other interesting result of this research, in relation to social

life, was the issue of Idir and Mahber. Idir and Mahber are among the

many socially constructed roles in many parts of Ethiopia that are

meant for the purpose of helping the needy and strengthening social

bond. Their main purpose is to link members of the community

together so that they would help each other when something good

(for instance, marriage) or bad (for instance, death) happens. As the

finding indicated resettler’s participation in Idir and Mahber, and in

other similar social roles, in their previous setting was incomparable

with their participation after they got displaced from inner city. The

finding boldly indicated that due to lack/shortage of social roles

and weak interest to participate, resettlers were experiencing poor

social wellbeing. In the same vein, Pankhurst and Piguet [1] made a

point that many ‘development’ programs are often in conflict with

the interests of local people worldwide. A number of communities

have witnessed serious resource depletion, economic, as well as

psychological impoverishment as a result of their displacement

in the name of ‘development.’ Lourenço- Lindel [25] also added

that relocation of low-income households from inner cities to the

outskirts would, undoubtedly, affect their livelihoods and informal

networks of mutual assistance. Furthermore, developmentinduced-

displacement affects coping strategies of people who are

displaced from the homes in which they have been living for several

years and relocated to new home and new environment. This

is consistent with the findings of this research. According to this

research, people who were displaced from their previous homes

and environment (Tikur Anbessa area) and relocated to Jemo

Three (new site) were experiencing psychological problems. Many

relocatees are experiencing psychological problems such as lack of

positive attitude about themselves, problems related to adaptation

to the new environment, a feeling of despair, and inability to lead

responsible life. The researcher of this study believed that one of

the factors for the poor psychological wellbeing of resettlers, in

addition to displacement, was the social breakdown indicated

above. The other factors that weakened psychological wellbeing

of resettlers was the cost of the houses. It was already discussed

in the ‘Introduction’ section that resettlers were unable to afford

the initial down-payment and monthly service payments since

they were economically poor. Furthermore, questions associated

with the quality of the buildings affected psychological wellbeing

of participants [32,33].

Conclusion

Displacement as the result of urban expansion and ‘slum

clearance’ has been increasing rapidly worldwide and is becoming

a significant phenomenon particularly in the large cities of the

developing world. As the demands of the urbanizing population

increases, notably in Africa and Asia, it is inevitable that the need for

infrastructure development will grow enormously and displacement

is likely to occur on massive scale World Bank [8],McDowell [7],

Pankhurst & Piguet [1]. As the research findings of this study

revealed, most people’s livelihoods were affected by displacement

programs. Resettlement requires careful and systematic planning

particularly in the selection of sites and verification of different

infrastructure and social services notably in terms of health and

education. Resettlers were brought to the site (Jemo Three) before

clinics, schools, and transportation services were not sufficiently

arranged. Addis Ababa city administration has to learn from such

mistakes for displacements and resettlements to be carried out in

the future. Many respondents explained the displacement process

as forced displacement. Consent from resettlers should be secured

because much of the literatures suggest that forced relocation is

more likely to be damaging to poor people’s livelihood prospects

than it is to improve them Cernea [10], Pankhurst & Piguet [1]. The

damage caused by resettlement far outweighs its benefits and the

vast resources wasted on the various programs would have been

more profitably employed elsewhere.

Recommendations

- Adequate planning and preparation for displacement is

vital from the part of the government.

- Displacees should be consulted and participated in the

plan and also in the process of displacement.s

- Some infrastructures, if not adequate, such as electricity,

transportation, clinics, and schools have to be built in the new

environment before relocating people.

- It is better to give displacees chance of choosing among

the available sites for resettlement than displacing them by

force.