Lupine Publishers | Journal of Urology & Nephrology

Abstract

Objectives: There are well recognised differences in health outcomes generally in society due to a range of socio-economic factors. We have compared survival outcomes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for aggressive bladder cancer in the national health service (NHS) and compared this with those with private health insurance (PHI).

Methods: This is retrospective study of 225 NHS and 32 PHI patients operated over 14 years by one surgeon. ASA scores were compared to approximate comorbidity status.

Results: There were significantly worse outcomes for all cause and disease specific mortality in the NHS group. There was no difference in ASA scores.

Conclusions: NHS patients fare worse than those with PHI. The reasons for this difference remain unclear. PHI patients have a more extensive lymphadenectomy and have fewer overall complications.

Keywords: NHS private insurance outcomes radical cystectomy bladder cancer

Introduction

We studied the outcome of patients with private health

insurance (PHI) compared to national health service (NHS) patients.

These patients had the same operation for muscle invasive cancer

of the bladder, and we looked to see whether there were significant

differences in both all-cause mortality and disease specific

mortality. We have attempted to see whether we can propose any

explanatory cause for such differences.

There are barriers in society that delay detection and the

treatment of cancers for those people with various social and

economic disadvantages [1]. This imbalance creates health

disparities such as differences in survival [2]. There are racial,

gender, ethnic and socioeconomic components which are reflected

in their insurance status [3].

Previous studies, mostly in the United States, although with

some English and Danish studies, have looked at the effect of

insurance status on outcomes of treatment for various cancers,

including urological cancers of the prostate, kidney and bladder

[4]. In the USA, the uninsured and those on Medicaid, have a worse

stage at presentation [3-7]and a lower all cause survival than those

with private insurance [2,1,8]. Worse disease specific mortality

has also been shown to be an independent risk factor with worse

outcomes for lower socio-economic status groups [9]. This finding,

however, was not confirmed by a British study specifically looking

at social deprivation [10]. Definitions of what constitutes adverse

social groups are complex and may affect robustness of data [11]. A

shift in classification of groups, pathological definitions and coding

of cause of death may explain the lack of improvement in survival

but not socioeconomic inequalities [11].

Many factors, including socio-demographic and clinical entities,

form a complex network influencing survival. In the USA Insurance

and socioeconomic status are predictors of mortality [1,8]. Uninsured patients are often treated at low volume centres[3].

Race and gender can also affect survival [12,13] as can communal

poverty [14,15].

It has been suggested that poorer health generally, as

demonstrated by more comorbidities and unhealthy lifestyle

behaviours account for this phenomenon [2,15]. The affordable care

act in the USA is an attempt to address the problem of the uninsured

presenting with more advanced disease and their subsequent lower

survival rates [16]. In addition, a negative association between

income and prevalence of physicians for bladder and renal cancer

mortality was found [17]. Those on Medicaid were less likely to

receive definitive treatment [18]. Similar effects of socioeconomic

status have been found in England [19]and Denmark [20].

These studies have all looked at the effect of all the range of

treatments, both curative and palliative, for all types of cancer,

including low- and high-grade disease which is of particular

importance when discussing bladder cancer.

For differences in outcomes after specific surgical treatments,

research has focused on radical prostatectomy. Insurance status is

associated with stage and cancer control [21]. Higher surgery rates

and lower radiotherapy rates were observed in private patients who

were more affluent [22]. We have shown previously that insurance

status is a protective risk factor with radical prostatectomy, but

wealth itself is not protective which may be due to different adverse

lifestyle behaviour[23].

There are few published studies pertaining to insurance

status and survival after a specific treatment for bladder cancer,

particularly radical cystectomy [24].

Effect of comorbidity and ASA score

Greater comorbidities as assessed by the ASA score, increase the likelihood of complications after radical cystectomy [25]. Patients with an ASA score of three or more have a greater complication rate [25]. Severe comorbidity is also associated with increased mortality [26,27]. The ASA score has been used to predict outcomes [28] and should be used for counselling and risk stratification [29,30]. In younger patients the ASA score can be useful despite EAU guidelines suggesting otherwise [31,32]. Neglect of comorbidities can cause misleading impressions of results [33] but the ASA score can be useful at to ascertain complication risk particularly with the type of urinary diversion and the time taken to do more complex surgery [34]. Comorbidity assessed using the Charlson score is useful for younger and older patients to predict toxicity of treatment and outcomes [35,36]. All-cause mortality has a stronger relation to comorbidity than disease specific mortality does [37].

Urinarydiversion

In general, the neobladder has a higher complication rate and longer stay in hospital [38] although it may be offered to most patients [39-41]. However, in practice, it still tends to be reserved for younger and fitter patients and thus may serve as a proxy for generally better health [42].

Methods

This is a retrospective study. The 257 radical cystectomy with

bilateral lymphadenectomy (with ileal conduit or neobladder)

operations were performed by one surgeon in both NHS and the

private sector in the same county of the UK, operated from 1999 to

2013 and followed up to the present day. There were 225 patients

from the NHS and 32 patients with private health insurance. These

were sequential patients who underwent potentially curative

operative and neoadjuvant/adjuvant treatments.

We compared various patient characteristics from health

records using Iqutopia for operation details, ICE, Bostwick

laboratories and Masterlab for pathology and PACS for imaging.

Medical statistics were done using Medcalc software for logistic

regression analysis to determine significant predictors of mortality

and progression. Fishers, Mann-Whitney, t tests and log rank tests

to compare Kaplan Meier. P values less than 0.05 were considered

significant.

The ASA score was documented by the attending anaesthetist

and retrieved from Iqutopia where available.

Results

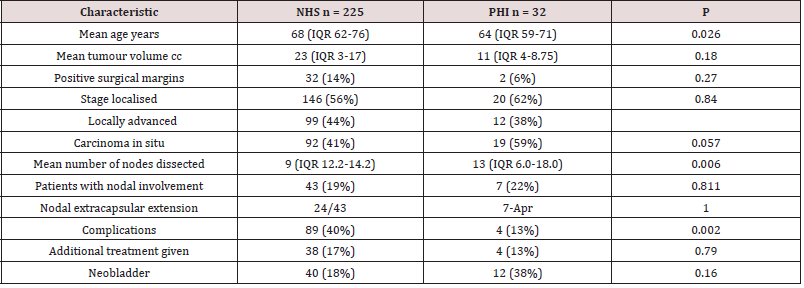

(Table 1-4) (Graph1-6)

There is a significant difference between the ages of the two

populations with NHS patients being older by four years. Private

patients had a greater degree of nodal dissection and fewer

complications. However, there was no difference in tumour volume,

positive surgical margin status, advanced stage, carcinoma in situ,

nodal involvement, nodal extracapsular extension. Further, there

was no difference in rates of neo adjuvant or adjuvant treatment

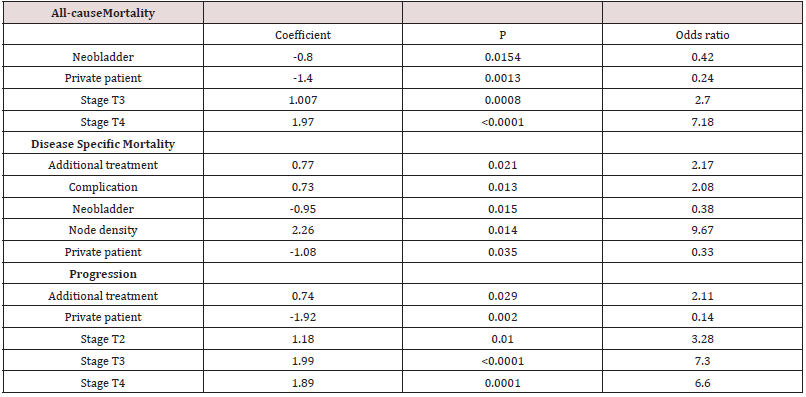

or the use of a neobladder. Logistic regression showed private

health status to have highly significant negative coefficients which

are protective in all cause and disease specific mortality as well as

lower progression rates.

All-cause mortality was associated with negative coefficients

for neobladder and PHI. Locally advanced stage was predictive of a

deleterious outcome.

Disease specific mortality also showed adverse coefficients for

additional treatments (adjuvant and neoadjuvant), complications

and nodal density involvement.

Progression was adversely affected by additional treatment and

increasing stage.

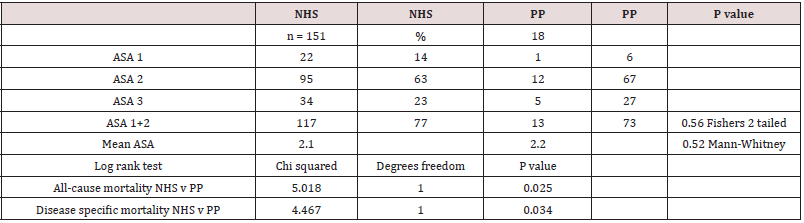

The ASA score was available in 169 of the 257 patients (66%).

There was no difference in the distributions of healthy and unhealthy patients as measured by this score. (ASA1 and 2 were

summated).

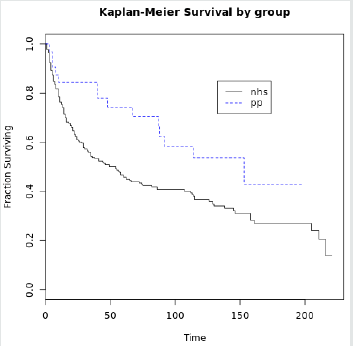

Log rank tests showed significant differences between the two

groups for mortality.

Discussion

This study has supported generally what is known about bladder cancer and the negative impact of lower socio-economic status. However former studies have looked at bladder cancer as a whole, which includes low grade and non-muscle invasive disease as well as advanced muscle invasive disease, inoperable cases, cases treated with radiotherapy and palliative cases all grouped together. This study looks at a subsection of these, those deemed appropriate for radical cystectomy. We have seen significant differences in both all-cause mortality and disease specific mortality. These differences have not been previously demonstrated. There are many gross and subtle differences that are difficult to detect with such a heterogenous disease in a heterogenous population. We propose that looking at a subgroup like this will decrease some of the obfuscating factors, by limiting geographical variation and the operation being performed by one surgeon only.

All-causemortality

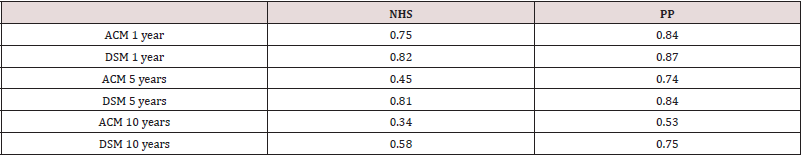

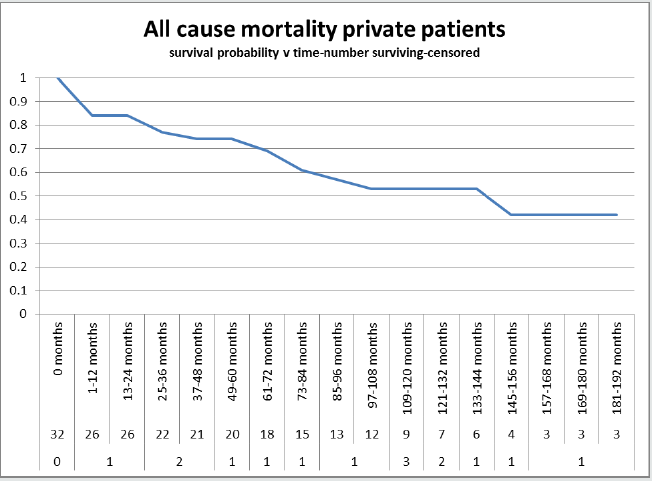

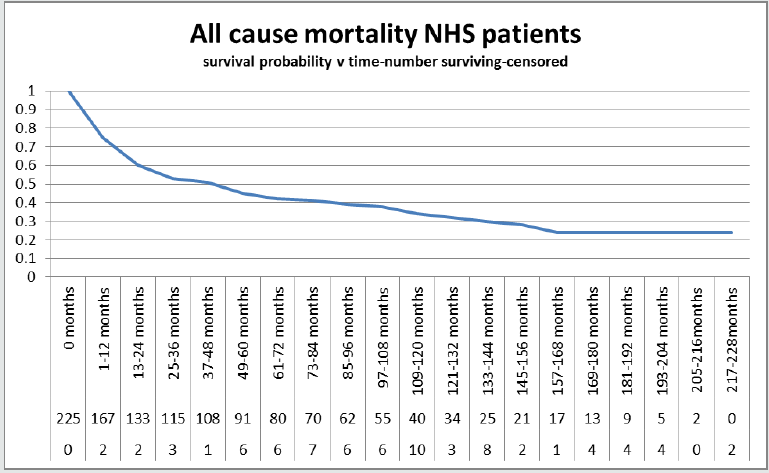

We have detected a significant difference in all-cause mortality

(Graph 5) with NHS patients (Graph 2)faring far worse (log rank

P = 0.025) and with an odds ratio 0.24 in favour of PP (Graph 1,

Table 2). Overall survival at one year is 0.75 for NHS and 0.84 for

PHI, and at five years it is 0.45 for NHS and 0.74 for PHI. Similarly,

at ten years for NHS patients it is 0.34 compared to 0.53 for PP

(Table 3). Numerous explanations have been proposed for the

worse prognosis overall for bladder cancer in the uninsured [1-

12]. Overall worse health is the proposed principal reason for a

worse all cause survival. We have tried to reflect potentially worse

comorbidities with the ASA score as an approximation to overall

health. There was, surprisingly, no significant difference detected

between the two groups (P = 0.56) (Table 4). Private patients were

four years younger on average and any chronic disease may not

have reached a critical point to effect outcome (P =0.026) (Table 1).

This was not a significant factor on regression analysis.

We do see that having a neobladder is a significant (P = 0.0154)

protective (negative coefficient -0.8) factor, perhaps standing as

a proxy for overall health [38,39], but there was no significant

difference in the use of this between the two groups (P=0.16) (Table

1). Locally advanced stage 3 and 4 were both significant as expected

[43, 44] with increasingly worse odds ratios (Table 2). The five-year

gold standard for radical cystectomy is about 50% [43-49], and our

population in the NHS reflects this. The patients with PHI fare much

better with a 5-year survival of 0.74.

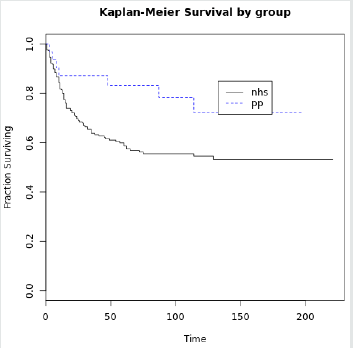

Diseasespecificmortality

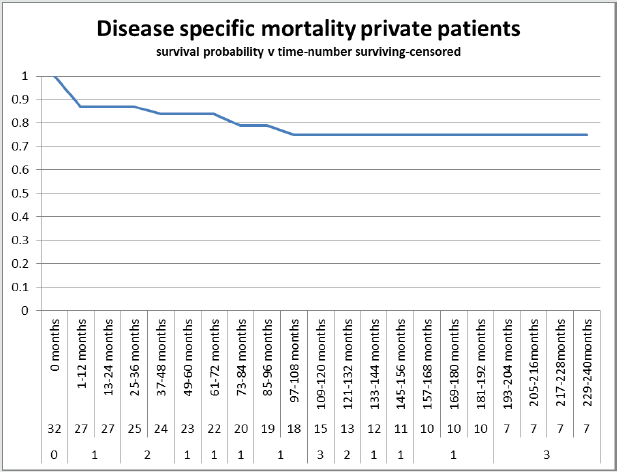

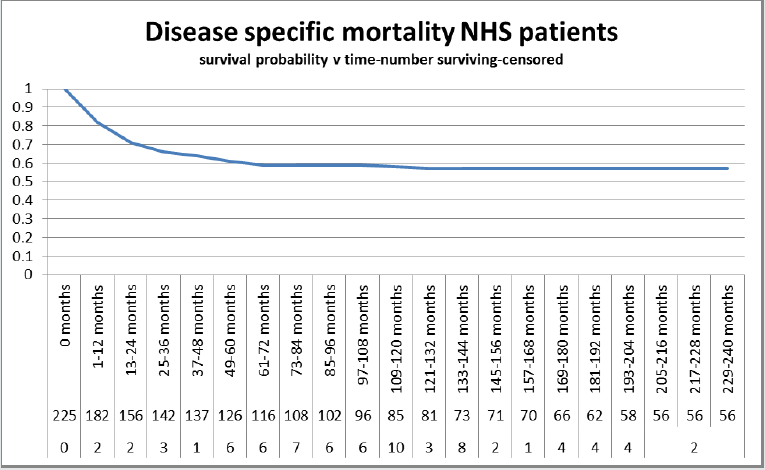

We found a significant protective coefficient and odds ratio of

0.33 in favour of private patients (Table2). There was a DSM of 0.87,

0.84 and 0.75 for PHI at one, five and ten years (Graph 3). This was

superior to NHS patients with DSM of 0.82, 0.81 and 0.58 (Table

3, Graph 4). This compares favourably with other series (49). The

log rank test comparing the two was significant (Graph 6, Table5).

Interestingly, the NHS mass of tumour was twice that of PHI, yet

there was no significant difference in tumour volume which one

might expect if there were a longer time to diagnosis in NHS patients

(11cc v 23cc P=0.18). Further, we did not detect a worse stage (NHS

56% localised, PHI 62% localised P=0.84) or a significantly greater

positive surgical margin rate in NHS patients (14% NHS v 6% PHI P

= 0.27). However, the trend was worse with all of these parameters

for NHS patients. There was no difference in rates of CIS between

the two.

The use of neobladder was, once again, a protective risk factor

(Table 2) which was used in 38% of PHI patients compared to 18%

in NHS patients, however this did not reach significance (P=0.16)

(Table 1).

Additional treatments, neo-adjuvant and adjuvant therapies,

were a significant detrimental risk factor (Table 2) but with no

significant difference between the two groups (NHS 17% and PHI

13% P=0.79).

The role of lymphadenectomy revealed no difference in

severity of extracapsular invasion (Table 1)(P=1.0) or in nodal

involvement with 19% of NHS patients having involved metastatic

deposits within at least one node, compared to 22% of PHI patients

(P=0.811). However, there was a significant difference in the

number of nodes retrieved at lymphadenectomy, with an average

of 9 for NHS and 13 for PHI patients (P=0.006). Node density is a

significant predictor of DSM with an odds ratio of 9.67 (Table2).

Complications, of all types, are a significant adverse predictor

for DSM. With a significantly worse rate in NHS, 40% compared to

PHI patients, 13% (P=0.002).

Progression

This also revealed PHI status to be protective and worse

outcomes were associated with need for additional treatment and

advancing stage.

Time to diagnosis and time to treatment from diagnosis may be

a factor, although studies are conflicting [50,51]. There is no lead

time bias (perceived increased survival with no effect on course of

cancer) as there is no screening protocol.

Conclusion

American studies have shown that insurance is important and

that even Medicaid patients do worse than private patients. We

concur that in the UK the NHS does not provide equal outcomes

compared with PHI when comparing radical cystectomy. There may

be social infrastructure issues involving hospital building capacity,

education, prevention, detection and treatment. Assistance to

patients to access and navigate healthcare systems and workplace

policies to encourage overall better health is needed. National

policies have been implemented to tackle this complex problem.

The NHS cancer plan 2000 in the United Kingdom (http.//www.doh.

gov.uk/cancer/pdfs/cancerplan.pdf) aims to reduce inequalities in

survival between rich and poor with a 62-day target to treatment.

The affordable care act in the USA highlights benefits of extending

health coverage to the uninsured [1].

We have found significant differences in outcomes for all cause

and disease specific mortality, yet the cause is elusive. We have

shown a direct comparison of NHS and PHI to reveal these outcomes

which can remain hidden in American studies as the SEER datebase

does not include uninsured patients by definition. There is no

difference in tumour volume, carcinoma in situ, advanced stage

or not, nodal involvement, extracapsular involvement of nodes,

rates of adjuvant and neo-adjuvant treatment. There are, however,

differences in complication rates and extent of lymphadenectomy

with favourable features pertaining to PHI.

We need to look for other ways to measure overall health that

include medical and lifestyle with socioeconomic components.

Limitations

The PHI cohort is small. We have not measured the time to diagnosis and to treatment. We have not been able to document the Charlson comorbidity score. We have not documented types of complications.

Read More About Lupine Publishers Journal of Urology Please Click on Below Link:

https://lupine-publishers-urology-nephrology.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.