Lupine Publishers | Orthopedics and Sports Medicine: open access

journal

Abstract

Purpose: We are presenting this pattern of a rare variant of a clavicle malunion with an apex posterior-inferior deformity. This occurred in an elite major junior hockey player during his draft season. This illustrates that such a deformity will most likely result in shoulder weakness, altered shoulder mechanics and may cause brachial plexus neurological findings. In addition, this can cause associated sterno-clavicular deformity which can lead to sternoclavicular joint subluxation secondary to the increased strain placed on the sternoclavicular joint from an apex posterior inferior malunited clavicle. Deformity of > 20 degrees in any direction interferes with normal motion and normal cortical strength even in a young patient.

Introduction: Symptomatic malunion is fortunately less frequently observed (4) since the significant shift to operative treatment for displaced shortened mid shaft clavicle fractures. Symptomatic patients are typically those with marked displacement and significant shortening at the fracture site. Patient’s report weakness of the involved shoulder with rapid fatigability plus an increased deformity comes with an increased risk of recurrent fractures. Although not commonly described in the literature, clavicle malunion usually has a very consistent deformity pattern. As illustrated by McKee et al, the patient usually presents with a complex three dimensional deformity with shortening, an anterior apex at the fracture site and associated joint pain around the shoulder or sternum (6). The influence of the coraco-clavicular and a cromio-clavicular ligaments on the fracture fragments is hypothesized to cause an effect on the displacement of these fractures which involves the lateral segment of the clavicle being carried forward by virtue of its retained a cromio-clavicular and residual coraco-clavicular attachments. Angulations are more acute the closer the break is to these pivot points. This has had associated significant alteration in normal clavico-scapular motion.

Method: Case report and literature review.

Conclusion: Symptomatic clavicular malunion is rare but definitely higher with non-operative management and can cause discomfort and shoulder weakness. Neurological symptoms and signs are more likely to occur in inferior malunited clavicle, particularly with an inferior-posterior deformity. We illustrated the steps necessary to correct all deformities and lengthen the clavicle using a long working length precountored plate construct. This has improved the clinical symptoms of the patient and illuminated the risk of repeat fracture due to deformity. Plate removal is planned but is still an unanswered question.

Keywords: Mid Shaft; Clavicle Symptomatic; Malunion; Nonunion; Deformity

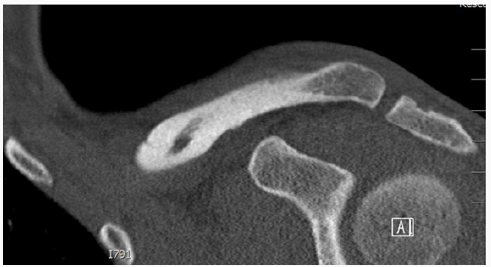

Case

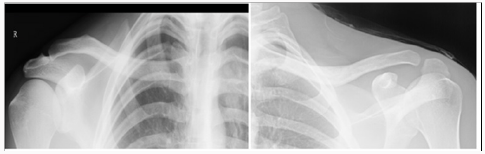

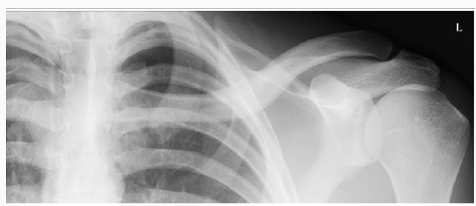

An 18 year old elite Canadian Hockey player presented with a new fracture to his left clavicle and associated pain at the sternoclavicular joint with an obvious deformity. He had sustained a previous injury to his left mid shaft clavicle two years ago playing hockey. This was treated on operatively and went on to heal with a 25 degree posterior-inferior deformity. A review of his initial injury films, from two years ago, illustrated a moderately displaced mid shaft clavicle with a significant amount of shortening (2 cm)due to inferior apex deformity( 25 degrees).However, it was decided to treat him on operatively as it was a closed injury in a relatively young male and he was neurovascularlyintact. His fracture healed with 2.5 cm of shortening, slight scapular inward rotation and a 25-30 degree posterior-inferior deformity. The sternoclavicular joint deformity on the left side stopped him from playing hockey at an elite level for about two months but a steroid injection seemed to remove most of his symptoms and allowed him to compete. He also complained of an ongoing occasional shoulder weakness and an occasional fleeting numbness in his arm and hand. This was significant enough to warrant a CT of the chest to rule out thoracic outlet syndrome.n 2010, the Czech Republic participated in the World Health OrgAn 18 year old elite Canadian Hockey player presented with a new fracture to his left clavicle and associated pain at the sternoclavicular joint with an obvious deformity. He had sustained a previous injury to his left mid shaft clavicle two years ago playing hockey. This was treated on operatively and went on to heal with a 25 degree posterior-inferior deformity. A review of his initial injury films, from two years ago, illustrated a moderately displaced mid shaft clavicle with a significant amount of shortening (2 cm)due to inferior apex deformity( 25 degrees).However, it was decided to treat him on operatively as it was a closed injury in a relatively young male and he was neurovascularlyintact. His fracture healed with 2.5 cm of shortening, slight scapular inward rotation and a 25-30 degree posterior-inferior deformity. The sternoclavicular joint deformity on the left side stopped him from playing hockey at an elite level for about two months but a steroid injection seemed to remove most of his symptoms and allowed him to compete. He also complained of an ongoing occasional shoulder weakness and an occasional fleeting numbness in his arm and hand. This was significant enough to warrant a CT of the chest to rule out thoracic outlet syndrome.nization WHO Research to determine the quality of medical decAn 18 year old elite Canadian Hockey player presented with a new fracture to his left clavicle and associated pain at the sternoclavicular joint with an obvious deformity. He had sustained a previous injury to his left mid shaft clavicle two years ago playing hockey. This was treated on operatively and went on to heal with a 25 degree posterior-inferior deformity. A review of his initial injury films, from two years ago, illustrated a moderately displaced mid shaft clavicle with a significant amount of shortening (2 cm)due to inferior apex deformity( 25 degrees).However, it was decided to treat him on operatively as it was a closed injury in a relatively young male and he was neurovascularlyintact. His fracture healed with 2.5 cm of shortening, slight scapular inward rotation and a 25-30 degree posterior-inferior deformity. The sternoclavicular joint deformity on the left side stopped him from playing hockey at an elite level for about two months but a steroid injection seemed to remove most of his symptoms and allowed him to compete. He also complained of an ongoing occasional shoulder weakness and an occasional fleeting numbness in his arm and hand. This was significant enough to warrant a CT of the chest to rule out thoracic outlet syndrome.

This 18 year old male continued to play elite major junior hockey (prime pathway to the NHL in Canada) then unfortunately sustained another injury where he was checked into the boards during an elite hockey game. He felt immediate pain and tenderness along his clavicle and therefore presented to the hospital emergency. Interestingly, since his initial incident, he had never been free of symptoms and he subsequently fractured his clavicle with relatively low trauma within 18 months of his last fracture. Plus he had significant sterno-clavicular associated symptoms with pain and anterior subluxation of the ipsilateral sterno-clavicular joint

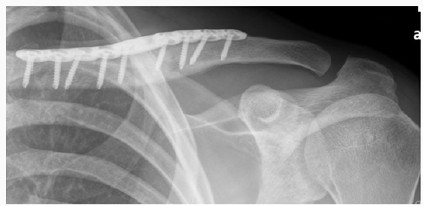

In the Emergency Department he was evaluated by the ER physician and the orthopaedic on call team. He had normal vital signs and good air entry bilateral chest, his neurological exam of both motor and sensory nerves of his left upper extremity showed no deficit, no signs of thoracic outlet syndrome and he illustrated a normal vascular exam. His investigation included x ray of his left clavicle with a contra lateral clavicle x ray for comparison. Both clavicles had an AP and orthogonal clavicular views (see images below). His clavicle demonstrated a more pronounced posterior-inferiorapex deformity (30-35 degrees), shortening and malrotation plus a significantly deformed (anterior subluxation) sternoclavicular joint as noted over the last year.

A detailed discussion with the patient about the findings was complete along with the possible operative and non operative treatment modalities available. Given the latest research and paper by McKee et al on the increased fracture rate in significantly deformed clavicles, an operative approach was chosen. This choice was also enhanced by the history of increased discomfort generally around the shoulder girdle discomfort plus the significant shoulder weakness, sterno-clavicular pain, neurological symptoms and reduced maximal function. We, therefore, elected to book him for a corrective osteotomy to restore length, alignment, rotation and angulations to augment the mechanics of his shoulder and the biomechanical ability of this clavicle to absorb an impact without re-fracturing.

Operative Procedure

The patient underwent general anaesthesia and was placed in a beach chair position in a 45 degree semi sitting position with a small pad behind the left shoulder blade and the involved upper extremity was draped freely with the distal arm placed in a sterile extremity drape. An oblique incision was made along the superior surface of the clavicle to expose the nonunion site. The skin and subcutaneous tissue was raised as a flap, and the underlying myofascial planes identified. This layer was raised as contiguous flaps and was preserved so that a two-layered closure could subsequently be achieved. Next, the malunion site was identified, and a long oblique, superior to inferior, osteotomy was performed. This provided a long osteotomy surface to correct the inferior apex deformity while allowing for the three dimensional correction with excellent bone to bone contact.

The osteotomy was performed with a, well irrigated, cooled, micro sagital saw. After careful dissection a small blunt Haworth elevator was placed underneath the clavicle to protect the neurovascular structures during the osteotomy and elevation of the deformity. Very importantly, the medullar canal was re-established, on both sides of the osteotomy, with a 3.5-mm drill-bit plus very aggressive curettage of the sclerotic bone in order to obtain an excellent opening in the medullar canal in the proximal and distal segments.

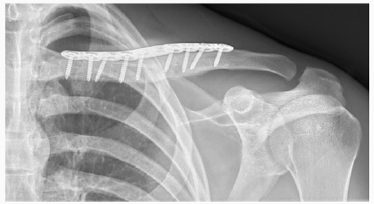

However, we have a very novel solution in the Czech Republic - whetSmall reduction clamps were then utilized to perform a reduction that would allow lengthening of the clavicle along with rotational and ambulatory correction utilizing the precountored plate as a reduction tool. First, shortening was corrected and held by translating the medial lateral fragment over the large surface osteotomy area to gain the planned length of 2.5 cm based on our preoperative planning. This was accomplished almost entirely by deformity correction. Secondly, rotation was corrected by rotating the lateral fragment about forty degrees clockwise until the flat surface of the lateral fragment was facing superior as desired. We then placed a long 10 whole precountored clavicle plate on the superior surface of the clavicle using the construct, with its long working length, to help gradually realign the bone back to the plate. This was and should be done very slowly and carefully as the underlying neurovascular structures can be tethered to the deformed bone. This was then held using absolute stability fixation with non locking screws on each side of the osteotomy. The screws were then gradually tightening of screws on either side of the deformity.r you are an individual patient crippled and dying for legal or iSmall reduction clamps were then utilized to perform a reduction that would allow lengthening of the clavicle along with rotational and ambulatory correction utilizing the precountored plate as a reduction tool. First, shortening was corrected and held by translating the medial lateral fragment over the large surface osteotomy area to gain the planned length of 2.5 cm based on our preoperative planning. This was accomplished almost entirely by deformity correction. Secondly, rotation was corrected by rotating the lateral fragment about forty degrees clockwise until the flat surface of the lateral fragment was facing superior as desired. We then placed a long 10 whole precountored clavicle plate on the superior surface of the clavicle using the construct, with its long working length, to help gradually realign the bone back to the plate. This was and should be done very slowly and carefully as the underlying neurovascular structures can be tethered to the deformed bone. This was then held using absolute stability fixation with non locking screws on each side of the osteotomy. The screws were then gradually tightening of screws on either side of the deformity.

Intra operatively, significant improvement in the shoulder contour was obvious as well as a noticeable reduction in the anterior subluxation of the sternoclavicular joint. Screw length was checked with an image at the end of the procedure. Deformity correction usually necessitates some screw changes as the initial screws can be long once the deformity is reduced. Wound closure was done in layers closing the myofascial flap over the plate and subsequently the subcutaneous tissue and the skin was re approximated with narrow skin staples.

Post operatively the patient was placed in a shoulder sling for comfort and scheduled for early physio to initiate shoulder and elbow function. His post op exam confirmed intact neurovascular status of his left upper extremity. Chest x ray taken in recovery room confirmed we had not created a pneumothorax. The operative procedure was performed as an outpatient. The patient went home on the same day and returned at 10 days for wound examination and staple removal. Aggressive physio was initiated that day following the initial gentle ROM and pendulum exercises which were initiated immediately post op (Figures 1-9).

Figure 1: Axial CAT scan of the chest delineating the sternoclavicular deformity related to the clavicle malunion.

Discussion

Clavicles fractures are common injuries and are reported to represent 2% to 5% of all adult fractures [1]. More recent evidence suggests that specific subsets of patients may be at higher risk for nonunion, symptomatic malunion, or suboptimal functional outcomes [2]. A recent meta-analysis suggests that the incidence of clavicle nonunion after nonsurgical treatment is approximately 5.9%, but can be as high as 15%for some fracture subtypes [3]. Nonsurgical treatment universally results in some degree of malunion; however, symptomatic malunion is fortunately quite low and is usually used particularly in very young patients [4]. Symptomatic patients are typically those with marked displacement at the fracture site, with shortening of >2 cm. Patients that are symptomatic may report weakness of the involved shoulder, rapid fatigability, numbness and paresthesia of the hand and forearm with elevation of the limb, and an asymmetric, “droopy,” “ptotic,” or “driven in”shoulder [5].

McKee et al performed a review of a cohort of patients to analyze the functional results of corrective osteotomy of a mal united clavicular fracture in patients with chronic pain, weakness, neurologic symptoms, and dissatisfaction with the appearance of the shoulder. Fifteen patients (nine men and six women with a mean age of thirty-seven years) who had amalunion following non operative treatment of a displaced mid shaft fracture of the clavicle were reviewed both preoperatively and postoperatively. The mean time from the injury to presentation was three years (range, one to fifteen years).Follow-up, at a mean of twenty months (range, twelve to forty-two months) postoperatively, illustrated that the osteotomy site had united in fourteen of the fifteen patients. All fourteen patients expressed satisfaction with the result. There was one nonunion, and two patients had elective removal of their plates. With regards to the patho anatomy of the deformed clavicle, McKee et al. noted that the deformity of the clavicle was a complex three-dimensional problem with all their patients illustrating a superior-anterior apex deformity. In his series there were certain consistent features seen in patients who presented with symptoms following non operative treatment and a healed clavicle. The hall mark characteristic is shortening in the medial-lateral dimension, with inferior displacement of the distal fragment and superior displacement of the proximal fragment. They, therefore, concluded that the shortening in the medial-lateral plane had a negative effect on muscle-tendon tension, and muscle balance. The anatomic boundaries of neurovascular structures were of paramount importance in the development of symptoms [6].

In a study by Edelson et al, he studied the bony anatomic details in 73 cadaver specimens which had clavicle malunions in different regions of the clavicle. According to the Allman classification. Edelson found that in the middle-third fractures, similar anterior angulations to the lateral third fracture malunion was indeed present. The most consistent finding at the middle-third level was that the lateral shaft fragment was almost invariably displaced posterior to the medial shaft fragment. The author also commented that initial anterior-posterior radiographs of clavicle fractures are often dominated by inferior displacement or ptosis of the lateral fragment. However, in the cadaveric specimens, anterior angulations rather than drooping of the lateral fragment were the predominant deformity. Although often initially displaced in a down ward direction, the lateral fragment does not usually heal in this position, unless it is a greenstick fracture as occurred in our patient.

Therefore the literature concludes that the principle deformity in a healed malunionis anterior, superior angulations. In this series there were only 4 cases in which the lateral clavicle healed with downward angulations of 20° or more at the fracture site as occurred in our young patient with his greenstick type of fracture. The author hypothesized that inferior displacement of the lateral fragment, which predominates on the initial radiographs, is most likely due to post-traumatic muscle a tony, principally of the deltoid and trapezius, similar to that which can cause the glenohumeral joint to appear subluxed after fractures of the humeral head and claimed that as soon as the muscle tonus returns, the clavicle resumes a horizontal orientation, and fracture position is then dominated by the pronators and internal rotators of the scapula and upper arm, which reposition the fragments into the anteriorsuperior apex position [7].

We believe that corrective osteotomy can lead to predictably good results (> 95%), however one should be careful with the inferior dissection as it can and has produced neurological and vascular issues in the past. So which fracture requires surgical correction? In general principles, according to the Canadian Orthopedic Trauma Society (COTS)and the McKee et al papers, “symptomatic deformity” with significant shortening of 2-3 cm , angulations deformity >30 degree or translation of >1cm . This has been supported in numerous repeated studies since 2008. In addition softer indications would be symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome, weakness or rapid fatigability with overhead activity, a relatively weak arm at over a year from the fracture or more commonly a combination of all of these symptoms, should be considered for an operative correction [6].

Another area of controversy between surgeons who treat this type of injury is the need for hardware removal to decrease the risk of re-fracture. Some surgeons prefer to remove the implant in all patients after clavicle fracture union, whereas others plan for additional surgery only if the patient complains of symptomatic hardware. In either case, adolescent patients undergoing surgical fixation for clavicle fracture must be warned of the possibility of return to the operating room to remove the implant.

Conclusion

Malunion of the clavicle with > 20 to 30 degrees of deformity and symptoms of weakness and malfunction should be considered for corrective osteotomy. The success rate is very high (.95%) and results in excellent patient satisfaction. This again supports McKee’s initial study that highlighted the clinical impact of mid shaft clavicle deformity and the importance of surgical reconstruction with an absolute stability. We also believe that if a surgeon carefully follows the steps of the surgical technique described in this case report; the incidence of vascular and neurological injuries can be mitigated although not entirely illuminated as a risk.

Read More Lupine Publishers Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Articles :