Lupine Publishers| Journal of Biostatistics & Biometrics

Abstract

Covid-19 has caused more than half a million deaths with more than ten million infections, as of late June 2020. Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic contributes to widespread psychological stressors with greater vulnerabilities of psychiatric illnesses, mounting serious challenges to mental health services. The psychological stimulus or stressors are expected to differ from the physiological reactivity, and the connection in the context of COVID-19 is still inconspicuous. Therefore, this paper attempts to uncover how the psychological stressors (emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and belief) contribute to the physiological changes in populations exposed to COVID-19. In this cross-sectional study, 355 adults living in remote and highly populated areas completed an online survey to evaluate the physiological and psychological symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic between the 20th and 30th of March 2020 in Irbid governorate, Jordan. The survey was uploaded online via Google Surveys and a link was distributed using WhatsApp and Facebook networks; we engaged active online community groups and leaders to validate this work and reach more audiences during the pandemic. Descriptive statistics, correlation, and multiple regression analysis to explore the data; Stepwise multiple linear regression is used to depict the effect of psychological on the physiological status. The findings explain that the overall physiological factor is significantly and positively correlated (at 1% level) with all psychological factors (Emotional, Behavioural, Cognitive, and belief). The highest correlation was with the emotional factor with a correlation of 0.68 (p <0.001) and the least correlated factor was cognitive with a correlation of 0.39. Those findings interpret that assessment, prevention, and treatment efforts of psychopathology including screening for mental health and psychological problems should focus on those groups with more emotional reactions and provide them with exceptional support to avoid acquiring further adverse physiological risks.

Keywords: COVID-19 Pandemic, Psychological and physiological Effects, Emotional and Behavioral Responses, Collective Trauma, Regression Analysis.

Introduction

Pandemics like COVID-19 have been reported to cause serious

psychological and physiological problems leading to different and

long-term disorders [1-3]. In critical crisis and situations, loss

of appetite, irritability, sleep disorder, fear, inattention, fatigue,

numbness, suicide attempt, as well as, despair may be acquired

by individuals experiencing or exposed to the traumatic event

[4]. In the case of the SARS outbreak, for example, a study showed

that individuals exposed to the infection have gained stressing

fear and felt stigmatization [5]. Other studies reported apparent

psychological symptoms like stress, anxiety, and depression among

those who closely experience the SARS pandemic, with potential for

causing long-term physiological, health, and mental implications [6-

7]. Similarly, several studies highlighted that alarming psychological

and physiological complications may also evolve among individuals

exposed directly or indirectly to COVID-19 pandemic, and thus,

demanding prompt care and psychological interventions [8].A study

investigated the mental health outcomes among frontline health

care workers in China directly engaged in the diagnosis, treatment,

and care of cases with COVID-19 to quantify depression, anxiety,

insomnia, and distress symptoms, and found that nurses and

women in particular experience some psychological distress and

mental health symptoms [2]. Another study investigated the issue of vicarious traumatization among the general public, members,

and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control,

and reported that the general public and medical staff, in particular,

suffer vicarious trauma symptoms [9]. The characteristics of mental

health associated with dysfunctional fear and anxiety of COVID-19

including hopelessness, suicidal ideation, spiritual crisis, and other

symptoms have also been reported [10]. Other recent studies also

revealed that patients and front-line healthcare workers are more

vulnerable to emotional impacts associated with COVID-19, and

explained that anxiety can arise during COVID-19 outbreaks among

communities following the first case of death, increased media

reporting and the escalating number of newly infected cases [11-

13]. Moreover, two studies focused on certain groups of population

such as aged and international migrants in China and found that

those groups, in particular, may experience additional distress and

will need special care with a psychiatric intervention [14-15].

Indeed, a considerable increase in the volume and forms of the

psychological complications and problems have been noted during

and due to the COVID-19 pandemic [1,16]. Such complications have

been reported to cause greater vulnerabilities and risks to different

psychological illnesses with serious physiological consequences;

making challenges to mental health practitioners and services [9].

A study focused on particular indicators of psychological stress

including emotional and behavioral responses, somatic responses,

and sleep quality in the Chinese population, and found that sleep

quality did not improve among front-line health workers and the

general public during early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic [17].

Another recent study also showed that moderate to high levels of

COVID-19 related anxiety in the UK population was significantly

associated with general somatic symptoms, and in particular with

gastrointestinal and fatigue symptoms [18]. This may predict that

as the pandemic progression elevates the level of anxiety, the

somatic symptoms may also escalate as time goes on. In response,

some countries, like China, crisis psychological intervention

teams have been allocated across many cities and hospitals to

avoid future psychological and physiological consequences [13].

Indeed, psychological stressors may trigger and associate with the

physiological responses in mammalian species including humans,

causing a wide range of physiological illnesses and symptoms [19-

21]. The psychological and physiological responses to emergencies

are a complex phenomenon (Olivier, 2015), and within the

context of COVID-19, this needs further investigation. It has been

recommended that a multidisciplinary mental health science

research should be a key part of the response to the COVID-19

pandemic at an international level, mainly with a focus on the

potential effects on individual and population mental health, as well

as, the effects on the brain function of those affected by or exposed

to the disease [8]. In this study, we assessed the psychological and

physiological responses in a population exposed to COVID-19 in

Irbid, Jordan. We also used a regression model to identify the effect

of the psychological four factors (emotional, behavioral, cognitive,

and life beliefs) on the physiological scores. Our main attempt is

to uncover how the psychological stressors (emotional, behavioral,

cognitive, and belief) may contribute to the physiological changes

in populations exposed to COVID-19.

Methods

Sampling

The focus of this study was to involve two categories of populations, individuals living in remote compared to highly populated areas. In general, large urban areas are expected to be more vulnerable to communicable infections similar to COVID-19, and therefore, well-prepared protocols, procedures, and systems may need to be in place to deal with the pandemic impacting such environments; high- level strategic decisions have been recommended to be made by urban leaders in such scenarios [22]. Yet, the question remains on how such needs can differ from the case of rural areas. Therefore, the participants include the general public living in both categories of the environment from the northern district of Jordan, Irbid. The survey was uploaded online using Google Surveys service and a link was distributed to the target audiences via WhatsApp and Facebook networks. Support and approval from community leaders and community groups on the Facebook network have been granted to help in the data collection process.

Measures

For this study, an administered self-report questionnaire was compiled to assess the psychological and physiological scores based on a comprehensive review of the existing international relevant scales including the Impact of Event Scale, Traumatic Stress Institute Belief Scale, and Vicarious Trauma Scale [23]. The survey consisted of 2 parts to identify the characteristics of the target audience and to measure the psychological and physiological scores. The first part asked about the level of knowledge about COVID-19 pandemic (on a scale from 1 “very weak” to 5 “very advance”) and demographic data (age group, gender, living area, marital status, and education level). The first part also asked four questions about the medical history of the participants, i.e., if the participant had any symptoms of flu or cold, diarrhea or indigestion, lately headache or high temperature, and have chronic diseases such as blood pressure, diabetes or kidney related. The medical history of individuals has been reported with an impact on some psychological or physiological symptoms in the case of traumatic events [24,25]. The second part of the survey consisted of two main dimensions; the physiological responses (11 items), and psychological responses (27 items). Those psychological responses consisted of emotional responses (nine items), behavioral responses (seven items), cognitive responses (five items), and life beliefs (six items). Each question score ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), where higher scores on this scale represent greater symptoms related to the higher impact of COVID-19 among populations.

Statistical Analysis

In this study, we used descriptive statistics, correlation, and multiple regression analysis. Descriptive statistics involved frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Stepwise Multiple Regression is used to identify and depict the effect of psychological four factors (Emotional, Behavioral, Cognitive, and Life Belief) on the physiological scores. The stepwise selection procedure is based on the p-value of the factors to identify which variables should retain in the final model. Stepwise finds the best subset of predictors and removing insignificant variables that were redundant or which were collinearly related to other variables [23]. The data was analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Co. LTD, Chicago, IL, USA). Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire reached 0.914, whereas that for each dimension ranged from 0.70 to 0.82, indicating positive reliability and validity of tool; other similar studies reported a higher level of Cronbach’s alpha for the same tool, more than 0.93. The factor analysis of the data using principal component analysis with a varimax rotation resulted with the cumulative variance contribution rate reached 61.91%. No problems were encountered with sphericity, sampling adequacy, or low commonalities, with excellent values of KMO=0.883, and a p-value<0.001, which indicates positive reliability and validity. The assumptions of normality, constant variance, and the independence of the observations were also checked, using residual [26].

Results

Participants and Health History

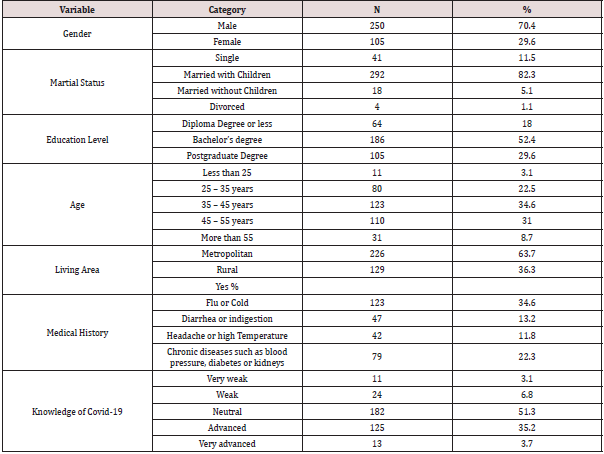

The initial sample consisted of 374 respondents, among these, 355 participants were considered for our study after excluding the data from 19 incomplete surveys. Of the participants, 70.4% were males (250), and 29.6% (105) were females as illustrated in Table 1. The vast majority of our participants (82.4%) are married with children and only 5.1% are married without children or other classes. The vast majority of participants (82%) are educated with at least a Bachelor’s degree. Most participants (65.5%) are in the middle age (35 – 55 years) and 63.7% of them live in the metropolitan area. Only 34.6% of participants had recent flu or cold, while only 13.2% suffer from diarrhea or indigestion problems. Only 11.8% of respondents lately suffered from a headache or high temperature and 22.3% of the respondents have some chronic diseases such as blood pressure, diabetes, or kidneys.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

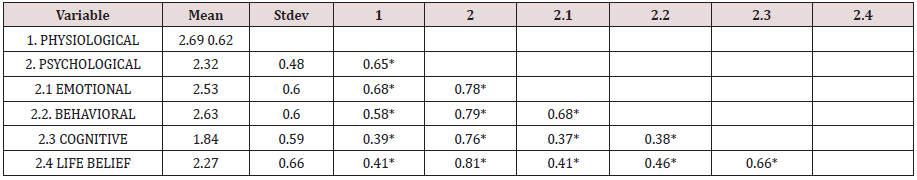

Table 2 reports the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the main factors of the study, namely, physiological and psychological factors. The psychological factor consisted of four sub-factors; emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and life belief responses [9]. All factors average were less than 3, meaning that the respondents don’t have any severe physiological nor psychological symptoms from COVID-19. The psychological average (2.69) was significantly higher than the physiological (2.32) average with a p-value <0.001. The least average in psychological sub- factors was for cognitive (1.84) and the maximum average was for behavioral (2.63). The physiological and psychological factors are positively and significantly correlated with a correlation of 0.65 (p- value<0.01). The physiological factor was also correlated significantly (at 1% level) and positively with all psychological factors (Emotional, Behavioural, Cognitive, and belief). The highest correlation was with the emotional factor with a correlation of 0.68 (p <0.001) and the least correlated factor was cognitive with a correlation of 0.39. N=355; * the correlation is significant at the 0.01 level.

Regression Analysis

Stepwise multiple linear regression is used to depict the effect

of psychological four factors (Emotional, Behavioural, Cognitive,

and Life Belief) on Physiological. The equation used to test this

relationship is as follows: Phys! = 𝛽” + 𝛽#Emotional + 𝛽$Behavioural + 𝛽%Cognitive + 𝛽&Belief + 𝜀!

Where𝜷𝟎, 𝜷 , … 𝜷𝟒 are the regression equation coefficients. The

results of the regression analysis are summarized in Table 3. Results

show that Emotional, Behavioural, and Cognitive are significant

at 5% level of significance while only Belief is not significant.

Psychological factors (Emotional, Behavioural, and Cognitive) are

positively and significantly associated with physiological with

coefficients of 0.578, 0.193, and 0.104, respectively. The values of

these coefficients can be interpreted as the effect of each variable on

physiological factor, the highest effect is for emotional followed by

Behavioural. For every one-unit increase in emotional, behavioral,

and cognitive scores increases the physiological score by 0.578,

0.193, and 0.104, respectively, holding the other variables constant.

The regression model F–value is 100.9 (p-value<0.0001) indicates

the fitness of the model with R- squared of 0.535, which means that

about 53.5% of the variation in the physiological score is explained

by Emotional, Behavioural, and Cognitive variables. Correlation

results revealed that belief is significant with physiological

factors, while regression analysis showed not. This means that

the variation in physiological can be explained by Emotional,

Behavioural, and Cognitive despite beliefs. Further analysis has

been made by incorporating some characteristics of the sample

into our regression model. The results of significant factors only

are summarised in Table 4. The knowledge found to be significant

with a p-value of 0.026 (significant at 5% level). The more the

knowledge level the less the physiological effect. The respondents

with moderate knowledge of COVID-19 have a less average of 0.21

(p-value<0.05) than respondents with low knowledge (reference

category). While respondents with a good knowledge of COVID-19

has a less average in physiological trauma of 0.23 (p- value<0.01).

Gender also found to be significant with a p-value of 0.021 with

a more average in physiological trauma index by 0.12 for males

than females. Education factor found to be significant with a less

physiological effect for high education levels with a p-value of

0.073 (significant at 10% level). Respondents with a bachelor’s

degree found to have on average 0.13 less in physiological trauma

index than respondents with a diploma degree or less (reference

category). While respondents with postgraduate degree level

have a less average in physiological trauma index by 0.16 than the

reference category. The area, marital status, and medical history

of respondents were not significant, meaning that they have the

same level of physiological effect across all levels of these variables.

Furthermore, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive variables were

significant (not the belief) even after including all characteristics of

respondents, which give more robustness of our results.

Read More About Lupine Publishers Journal of Biostatistics & Biometrics Please Click on Below Link: https://lupine-publishers-biostatistics.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.