Introduction: Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of functional endometrial tissue consisting of glands and/ or

stroma located outside the uterus [1], although implanted ectopically, this tissue presents histopathological and physiological

responses that are similar to the responses of the endometrium [2].

Clinical Features: Endometriosis usually becomes apparent in

the reproductive years when the lesions are stimulated by

ovarian hormones. Forty percent of the patient’s present symptoms in a

cyclic manner, which are usually related with menses Pelvic

pain, infertility and dyspareunia are the characteristic symptoms of the

disease, but the clinical presentation is often non-specific

[1].

Diagnosis and Investigations: A precise diagnosis about the

presence, location and extent of rectosigmoid endometriosis is

required during the preoperative workup because this information is

necessary in the discussion with both the colorectal surgeon

and the patient. Furthermore, almost all patients with intestinal

endometriosis have lesions in multiple pelvic locations and it is

difficult to know what symptoms are caused by the intestinal disease

versus the pelvic disease.

Treatment: Treatment must be individualized, taking the

clinical problem in its entirety into account, including the impact of

the disease and the effect of its treatment on quality of life. Pain

symptoms may persist despite seemingly adequate medical and/

or surgical treatment of the disease. In such circumstances, a

multi-disciplinary approach involving a pain clinic and counselling

should be considered early in the treatment plan.

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of functional

endometrial tissue consisting of glands and/ or stroma located

outside the uterus [1], although implanted ectopically, this tissue

presents histopathological and physiological responses that are

similar to the responses of the endometrium [2].

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The reported prevalence of endometriosis is 1%-20% in

asymptomatic women, 10%-25% in infertile patients and 60%-

70% in women with chronic pelvic pain [1]. Endometriosis is a

common benign disease among women of reproductive age and

affects the intestinal tract in 15%-37% of all patients with pelvic

endometriosis [3]. Multiple births and extended intervals of

lactation decrease the risk of being diagnosed with endometriosis,

whereas nulliparity, early menarche, frequent menses, and

prolonged menses increase the risk [4]. Endometriosis also

appears to be associated with a taller, thinner body habitus and

lower body mass index [5]. The prevalence appears to be lower in

blacks and Asians than in Caucasians [6]. Growth and maintenance

of endometriotic implants are dependent upon the presence of

ovarian steroids. As a result, endometriosis occurs during the active

reproductive period: women aged 25 to 35 years [6]. Other factors

that appear to play important roles in determining if a woman will

develop the clinical condition include [7]:

a) Reproductive lifestyle, especially a delay in childbearing

b) Poorly understood immunological factors

c) Some environmental factors, probably including exposure

to a range of environmental toxins

d) Reproductive tract occlusion, such as an imperforate

hymen.

Pathogenesis

Endometriosis is a common disease of unknown etiology. Many

theories have been proposed to explain this condition: retrograde

menstruation theory, metaplastic, transformation, the migration of

cells through the lymphatic system or via hematogenous spread,

Iatrogenic during CS. However, other factors, immunological,

genetic and familial, could be involved in the pathogenesis of this

disease [1].

Sampson’s Theory of Retrograde Menstruation

The implantation theory proposes that endometrial tissue

passes through the fallopian tubes during menstruation, then

attaches and proliferates at ectopic sites in the peritoneal cavity.

Recent studies using laparoscopy have demonstrated that

retrograde menstruation is a nearly universal phenomenon in

women with patent fallopian tubes. Classic studies performed in

the 1950s demonstrated viability of sloughed endometrial cells

and the capacity to implant at ectopic sites. Patients with mullerian

anomalies and obstructed menstrual flow through the vagina may

have an increased risk of endometriosis. The anatomic distribution

of endometriosis also provides evidence for Sampson’s theory [8].

Coelomic Metaplasia Theory

The theory of coelomic metaplasia proposes that endometriosis

may develop from metaplasia of cells lining the pelvic peritoneum.

Iwanoff and Meyer are recognized as originators of this theory. A

prerequisite of the coelomic metaplasia theory is that mesothelial

cells lining the ovary and pelvic peritoneum contain cells capable

of differentiating into endometrium. An attractive component

of the coelomic metaplasia theory is that it can account for the

occurrence of endometriosis anywhere mesothelium is found.

This includes reports of endometriosis occurring in the pleural

cavity. Pleural endometriosis could result from local metaplasia

of pleural mesothelium. On the other hand, it could also result

from transdiaphragmatic passage of peritoneal fragments of

endometrium as well as vascular metastasis of endometrium.

Coelomic metaplasia is thought to account for the rare occurrences of

endometriosis reported in males. In these reports of endometriosis,

the men were all undergoing estrogen therapy. Although coelomic

metaplasia was a possibility, estrogen stimulation of mullerian rests

could not be excluded. Likewise, the occurrence of endometrial

carcinoma in males is thought to possibly arise from mullerian

remnants. Still, further support for the coelomic metaplasia theory

may be found in the study of benign and malignant epithelial

ovarian tumors. Both are considered to be derivatives of germinal

epithelium. The presence of ovarian surface endometriosis could

be accounted for by this type of transformation [8].

Induction Theory

The induction theory is an extension of the coelomic metaplasia

theory. This theory proposes that menstrual endometrium produces

substances that induce peritoneal tissues to form endometriotic

lesions [8].

Embryonic Rests Theory

Von Recklinghausen and Russell are credited with the

theory that endometriosis results from embryonic cell rests.

These embryonic rests, when stimulated, could differentiate

into functioning endometrium. As described above, rare cases

of endometriosis have been reported in men. Transformation of

embryonic rests is a plausible explanation for this phenomenon [8].

Lymphatic and Vascular Metastasis Theories

The lymphatic metastasis theory of endometriosis is often

referred to as Hal ban’s theory. He reported that endometriosis

could arise in the retroperitoneum and in sites not directly opposed

to peritoneum. Sampson had also suggested that endometriosis

could result from lymphatic and hematogenous dissemination

of endometrial cells. An extensive communication of lymphatics

has been demonstrated between the uterus, ovaries, tubes, pelvic

and vaginal lymph nodes, kidney, and umbilicus. Metastasis

of endometrial cells via the lymphatic system to these areas is

therefore anatomically possible. These findings are consistent

with a literature review showing a 6.7% incidence of lymph node

endometriosis in 178 autopsy cases. Lymphatic and vascular

metastasis of endometrium has been offered as an explanation for

rare cases of endometriosis occurring in locations remote from the

peritoneal cavity. In addition to pleural tissue, endometriosis has

been reported in pulmonary parenchyma. Vascular or lymphatic

metastasis may also explain cases of endometriosis that have been

reported in bone, biceps muscle, peripheral nerves, and the brain

[8].

Composite Theory

Javert proposed a composite theory of the histogenesis of

endometriosis which combines the implantation, vascular/

lymphatic metastasis, as well as a theory of direct extension of

endometrial tissue through the myometrium. Along similar lines,

Nisolle and Donnez have recently argued that the histogenesis

of endometriosis depends on the location and ‘type’ of the

endometriotic implant. For example, peritoneal endometriosis can

be explained by the implantation theory. Ovarian endometriomas

could be the result of coelomic metaplasia of invaginated ovarian

epithelial inclusions. Rectovaginal endometriosis, which often

resembles adenomyosis, could result from metaplasia of Mullerian

remnants located in the rectovaginal septum. These composite

theories are attractive in that they recognize a multifaceted

mechanism of histogenesis. It seems logical that a disease with such

variable manifestations may originate via several mechanisms [8].

Altered Immunity

Alterations in immunologic response to retrograde

menstruation have been implicated in the genesis and maintenance

of the endometriotic lesion. This defective immunosurveillance may

lead to decreased clearance of menstrual debris from the peritoneal

cavity and may allow for attachment of ectopic endometrium to

peritoneal surfaces. An abnormal immune response could also

promote the persistence and growth of ectopic endometrial tissue

[8].

The “Neurologic Hypothesis”

It is a new concept in the pathogenesis of endometriosis:

There is a close histological relationship between endometriotic

lesions of the large bowel and the nerves of the large bowel wall.

Endometriotic lesions seem to infiltrate the large bowel wall

preferentially along the nerves, even at distance from the palpated

lesion, while the mucosa is rarely and only focally involved [9].

Pathology and Sites of Involvement

Sites

Endometriosis can be divided into intra- and extraperitoneal

sites. In decreasing order of frequency, the intra-peritoneal

locations are ovaries (30%), uterosacral and large ligaments

(18%-24%), fallopian tubes (20%), pelvic peritoneum, pouch

of Douglas, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Extra-peritoneal

locations include cervical portio (0.5%), vagina and rectovaginal

septum, round ligament and inguinal hernia sac (0.3%-0.6%),

navel (1%), abdominal scars after gynaecological surgery (1.5%)

and caesarian section (0.5%). Endometriosis rarely affects extraabdominal

organs such as the lungs, urinary system, skin and the

central nervous system [1]. Endometriosis affects the intestinal

tract in 15% to 37% of patients with pelvic endometriosis [10],

involvement have been reported from the small bowel to the anal

canal, but more frequently the disease involves the rectum and the

sigmoid colon (74%), followed by the rectovaginal septumn (12%),

cecum (2%), and appendix (3%) . When the ileum is involved, the

most common tract is the distal part. A full-thickness involvement

of the colonic wall is infrequent since the mucosa is usually spared.

One of the classic locations is the anterior rectal wall in the region

of the pouch of Douglas. This can be single nodule or can simulate

a cancer. Because of the invasive appearance, the disease can be

mistaken for cancer [11].

Gross and Microscopic Pathology of Bowel Endometriosis

The appearance and size of the implants are quite variable.

Areas of endometriosis appear as raised flame-like patches, whitish

opacifications, yellow-brown discoloration, translucent blebs, or

reddish or reddish-blue irregularly shaped islands. The peritoneal

surface may be scarred or puckered.

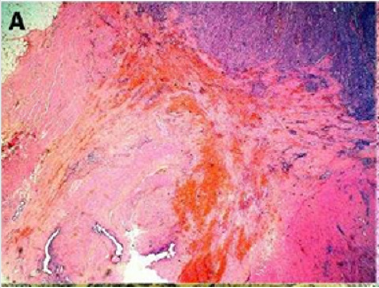

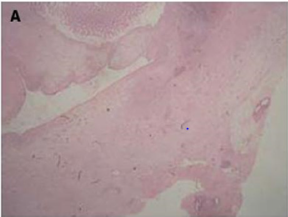

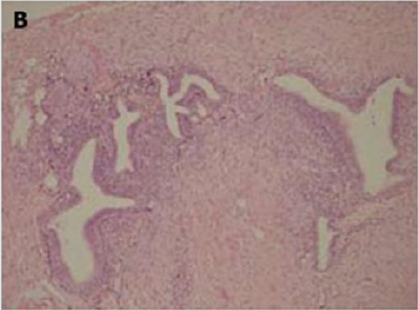

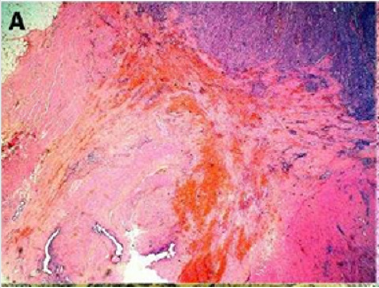

The Microscopic Appearance

Of endometriotic tissue is similar to that of endometrium in the

uterine cavity; the two major components of both are endometrial

glands and stroma. Unlike endometrium, however, endometriotic

implants often contain fibrous tissue, blood, and cysts (Figure 1(a)

& 1(b)).

Figure 1(a): Low-power image of the colonic wall, with

a few endometrial glands and stroma embedded in the

muscular layer.

Figure 1(b): High-power view of the colonic wall, with

endometrial glands and stroma embedded in the smooth

muscle of the colon [12].

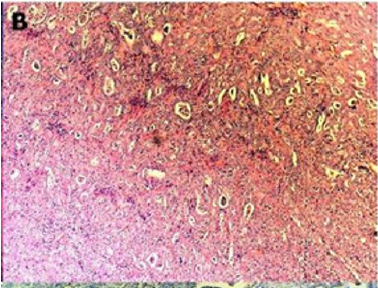

Link to Cancer

Endometriosis is considered a benign disorder; however, it

shares some of the characteristics of malignancy, such as abnormal

morphology, deregulated cell growth, cellular invasion, and

neoangiogenesis. The glandular epithelium occasionally displays

DNA aneuploidy. In vitro evidence suggests that endometriosis

may have a monoclonal origin. In addition to being monoclonal,

endometriotic deposits showed loss of heterozygosity in 28%

of lesions. In 2002, Nezhat et al. with immunohistochemistry,

found that alterations in bcl-2 and p53 may be associated with

the malignant transformation of endometriotic cysts [12]. The

development of a malignancy is a relatively common complication

of endometriosis. In fact, several publications have reported

malignant neoplasms arising from endometriosis. Most of

these publications are case reports or refer to a small series of

patients presenting either ovarian carcinomas with associated

endometriosis or invasive endometrioid adenocarcinomas

involving adjacent pelvic structures. Malignant transformation of

extraovarian endometriosis, including the intestinal tract, however,

has not been reported as frequently. The largest reported series

of neoplastic changes in gastrointestinal endometriosis includes

17 cases [10] (Figure 2(a-d)). Some studies suggest that the

development of malignancies may occur in up to 5.5 % of female

patients with endometriosis. Only 21.3% of the cases arise from

extragonadal pelvic sites, and endometriosis-associated intestinal

tumors are even rarer. Malignant transformation of primary

gastrointestinal endometriosis without pelvic involvement is

uncommon, and its real incidence is unknown. It can mimic a

primary gastrointestinal neoplasm. Most of these neoplasms

are carcinomas, but sarcomas and müllerian adenosarcomas have also been described. Petersen et al, in a large review of the

previously published endometrioid adenocarcinomas arising in

colorectal endometriosis, report less than 50 cases of neoplastic

transformation, 22 of which were adenocarcinomas. The others

included sarcomas and mixed müllerian tumors. The progression to

invasive cancer has been related with hyperestrogenism, either of

endogenous or of exogenous origin. A possible genetic background

favoring the onset of cancer has been reported in some patients

without hyperestrogenism and with a family history of cancer. The

anatomic distribution and frequency of these cancers parallel the

occurrence of which benign endometriosis is found at various sites.

In order to classify a malignancy as arising from endometriosis,

strict histopathologic criteria need to be fulfilled. Sampson first

proposed these criteria in the year 1925. He suggested that the

following should be fulfilled:

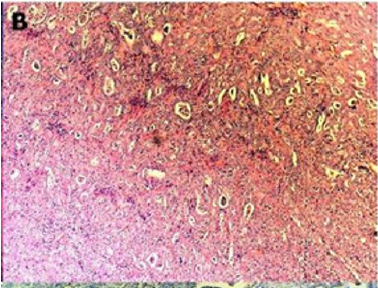

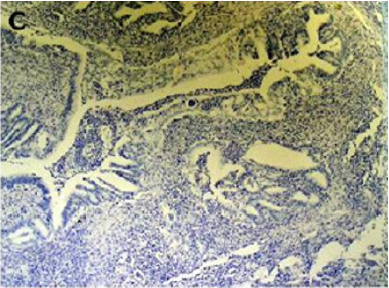

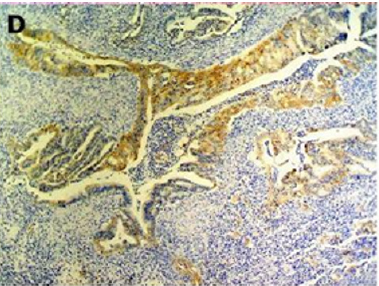

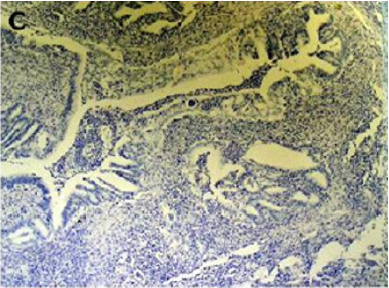

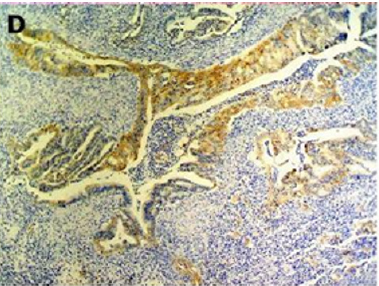

Figure 2(a): Rectal endometriod adenocarcinoma with

adjacent focus of endometriosis (hematoxylin-eosin, 20x).

Figure 2(b): Rectal endometriod adenocarcinoma

endometriosis (hematoxylin-eosin, 100x).

Figure 2(c): Cytokeratin 20 immunostaining negative

(100x).

Figure 2(d): Cytokeratin 7 immunostaining positive (100x).

[10]

a) the presence of both malignant and benign endometrial

tissue in the same organ.

b) the demonstration of cancer arising in the tissue and not

invading it from elsewhere.

c) the finding of tissue resembling endometrial stroma

surrounding characteristic glands.

Years later, Scott suggested an additional qualification to

complete Sampson’s criteria: the demonstration of microscopic

benign endometriosis contiguous with the malignant tissue [10].

Endometriosis and its possible malignant changes should be taken

into account in the differential diagnosis of intestinal masses in

females. Also, clinical suspicion for malignancy should be aroused

in patients with abdominal pain or rectal bleeding and a previous

history of quiescent endometriosis. Recognition of these lesions

is important because of the different management required by

primary gastrointestinal neoplasms and by those arising from

endometriosis. These differences may have significant clinical

implications [10].

Clinical Features

Endometriosis usually becomes apparent in the reproductive

years when the lesions are stimulated by ovarian hormones. Forty

percent of the patient’s present symptoms in a cyclic manner,

which are usually related with menses Pelvic pain, infertility and

dyspareunia are the characteristic symptoms of the disease, but the

clinical presentation is often non-specific [1]. Symptoms are initially

cyclical but may become permanent when the lesions progress. It is

difficult to establish a preoperative diagnosis of GI endometriosis,

because GI tract symptoms can mimic a wide spectrum of diseases,

including irritable bowel syndrome, infectious diseases, ischemic

enteritis/colitis, inflammatory bowel disease and neoplasm. GI

endometriosis patients present with relapsing bouts of abdominal

pain, abdominal distention, tenesmus [1], constipation and

diarrhoea. Rectal bleeding and pain during defecation may also

occur. Endometriosis infiltrating the muscularis propria may lead

to localized fibrosis in the bowel wall, strictures, and small or large

bowel obstruction. The true incidence of endometriosis causing

bowel obstruction is unknown, although complete obstruction of

the bowel lumen occurs in less than 1% of cases. Endometriosis

of the distal ileum is an infrequent cause of intestinal obstruction,

ranging from 7% to 23% of all cases with intestinal involvement.

The incidence of intestinal resection for bowel obstruction is 0.7%

among patients undergone surgical treatment for abdominopelvic

endometriosis [1]. Rectal bleeding may be caused by mucosal injury

during the passage of stools through a stenosed colon with the

intramural endometriotic tissue increased at the time of menses if

it occurs. Colonic mucosa heals rapidly, and no signs are detectable

at endoscopy [1] (Table 1).

Table 1:

Differential diagnosis [1]

a) irritable bowel syndrome,

b) infectious diseases,

c) ischemic enteritis/colitis,

d) inflammatory bowel disease

e) neoplasm

f) Other causes of intestinal obstruction (Acute/chronic,

small/large bowel)

Diagnosis and Investigations

A precise diagnosis about the presence, location and extent of

rectosigmoid endometriosis is required during the preoperative

workup because this information is necessary in the discussion

with both the colorectal surgeon and the patient. Furthermore,

almost all patients with intestinal endometriosis have lesions

in multiple pelvic locations and it is difficult to know what

symptoms are caused by the intestinal disease versus the pelvic

disease. In particular, in the case of sigmoid endometriosis, the

lesion cannot be suspected at clinical examination, which is why

sigmoid endometriosis is often diagnosed only during surgery.

Although several radiological techniques have been proposed for

the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis, data are inconclusive, and no

gold standard is currently available [13].

Colonoscopy

Although endoscopic diagnosis of colonic endometriosis has

been reported, the mucosa is usually normal or shows minimal

mucosal abnormalities, friability, extrinsic process or fibroses

stenoses [1]. Endoscopic biopsies usually yield insufficient tissue

for a definitive pathologic diagnosis as endometriosis involves

the deep layers of the bowel wall [14]. Endometriosis can induce

mucosal changes without any specific pattern, which mimic

findings of other diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease,

ischemic colitis or neoplasm [1]. Colonoscopy is helpful to rule out

colorectal malignancy [11].

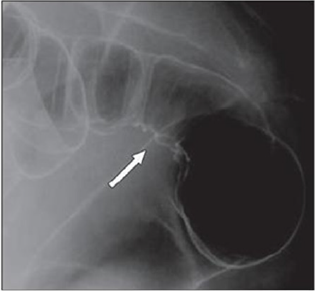

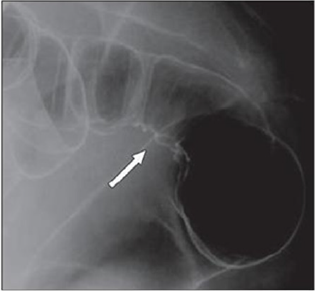

Double Contrast Barium Enema

Radiologically, lesions of endometriosis are either of

constricting and polypoid type or both. On barium studies,

radiographic findings caused by implants in the ileum are similar to

those in the colon. Rectosigmoid or cecal endometriosis on double

contrast barium enema studies is seen as an extrinsic mass with

speculation and tethering of folds [1]. Shortening or flattening of

the bowel wall, crenulation of the mucosa, or a combination of

these factors [15], Double-contrast barium enema may be effective

in determining the precise location of the endometriotic nodules,

but it cannot clearly demonstrate the depth of parietal involvement.

Furthermore, the experience of the radiologist in the diagnosis of

bowel endometriosis remains a critical limit of this technique [13]

(Figures 3 & 4(a & b)).

Figure 3: Thirty-four years old woman with suspected intestinal implants of endometriosis. A and B, Lateral A and oblique B

spot images show three endometriotic lesions exhibiting extrinsic mass effect with crenulation of contour and speculation that

are direct signs of infiltration of bowel wall (arrows). Small polypoid lesion (arrowhead) is benign tubular adenoma confirmed

at surgery [15].

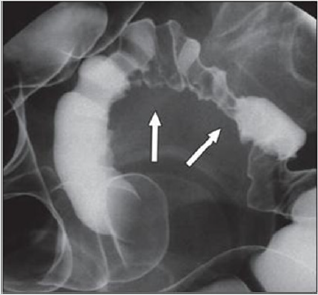

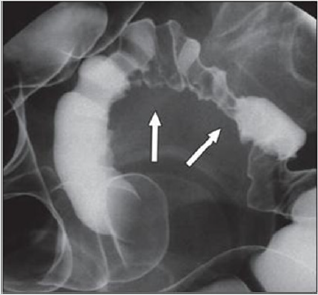

Figure 4(a): Twenty-eight years old woman with suspected intestinal implants of endometriosis and finding of rectal

localization of intestinal endometriosis. DCBE image shows extrinsic mass effect and speculation (arrow) of rectal wall that

appears infiltrated [15].

Figure 4(b): Twenty-three years old woman with suspected intestinal implants of endometriosis. DCBE examination showing

pathologic pelvic process involving bowel serosa at rectosigmoid junction. Finding of extrinsic mass effect and speculation

(arrows) owing to poor wall distention after air insufflation suggesting wall infiltration [15].

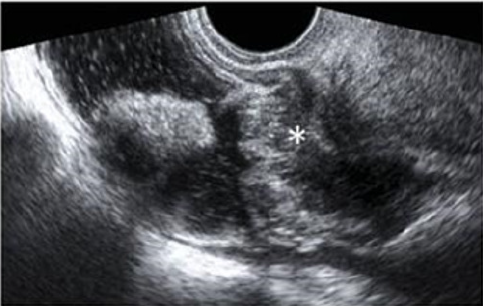

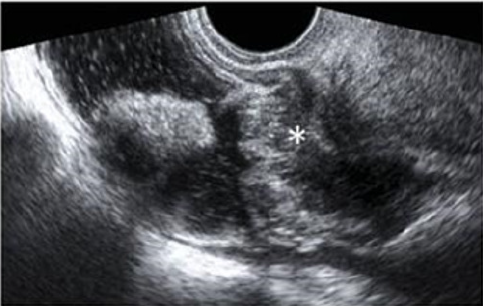

Transvaginal Us

Transvaginal ultrasonography can be useful not only in the

first-line exploration of the pelvic cavity, but also in diagnosing

rectosigmoid endometriosis. However, relevant limitations of

transvaginal ultrasonography consist in the impossibility of

determining the exact distance of rectal lesions from the anal margin

and of evaluating precisely the depth of rectal wall involvement. In

addition, locations above the rectosigmoid junction might be beyond

the field of view of a transvaginal approach and limited by the

presence of air for a transabdominal approach [15]. Transvaginal

us combines with rectal water contrast is more accurate than TVS

in diagnosing rectal infiltration reaching at least the muscularis

propria in women with rectovaginal endometriosis. However, this

exam cannot determine whether the infiltration reaches the rectal

submucosa. RWC-TVS may be more painful than TVS, therefore

it could be used when TVS cannot exclude the presence of rectal

infiltration in women with rectovaginal endometriosis [15] (Figure

5).

Figure 5: A large rectovaginal nodule infiltrating the bowel muscularis (indicated by the asterisk) demonstrated by Rectal

Water Contrast- Transvaginal Sonography (RWC-TVS) [16].

CT & MSCT

CT is not the primary imaging modality for evaluation of

bowel endometriosis, although it can occasionally demonstrate

a stenosing rectosigmoid mass. Multislice CT (MSCT) has a great

potential for detecting alterations in the intestinal wall, especially

if it is combined with enteroclysis (MSCTe). Biscaldi et al carried

out a study on 98 women with symptoms suggestive of colorectal

endometriosis and MSCTe identified 94.8% of bowel endometriotic

nodules [1]. Biscaldi et al reported the usefulness of multislice CT

combined with distention of the colon by rectal enteroclysis for

bowel endometriosis. The sensitivity was 98.7% and specificity

was 100% in identifying women with intestinal endometriosis.

This method is thought to be very helpful for diagnosing intestinal

endometriosis, but requires bowel preparation, such as the need

for a low-residue diet for 3 d, drinking of 4-6 doses of a granular

powder dissolved in 500 mL of water per dose and intravenous

administration of iodinated contrast medium. This technique is

thus inappropriate for patients with obstructive symptoms or

allergy to iodinated contrast medium [3] (Figures 6 & 7).

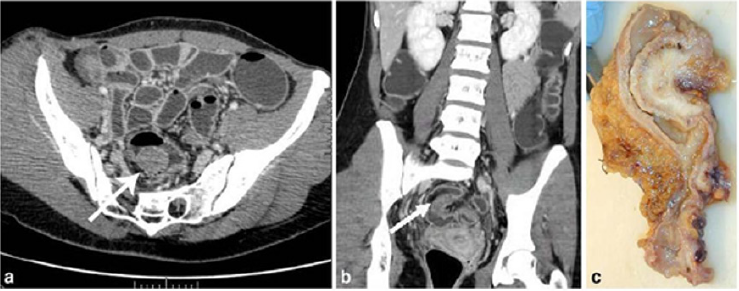

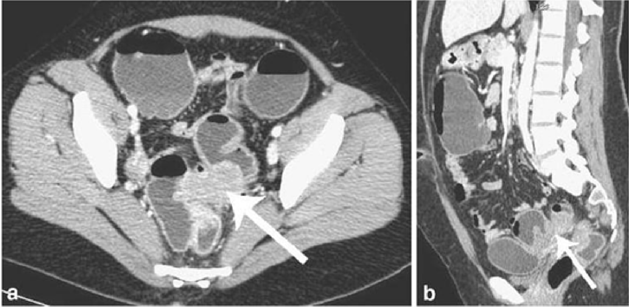

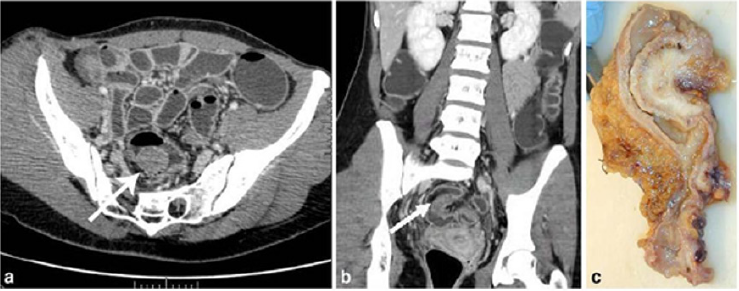

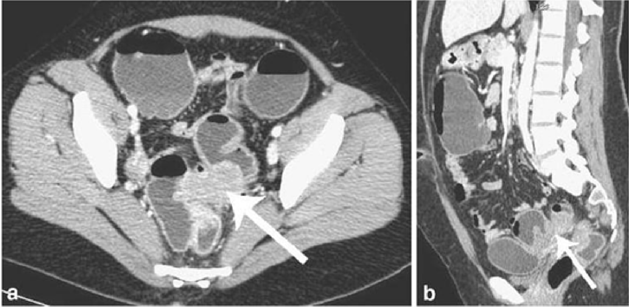

Figure 6: Endometriotic nodule infiltration the muscular layer, A: Axial MSCTe image of the abdomen, the arrow indicates

the endometriotic nodule. The lesion is enhanced, and it infiltrates the bowel wall involving the muscular layer. B: Coronal

reconstruction demonstrating the extension of the sigmoid endometriotic nodule (indicated by the arrow) C: Formaldehydefixed

resected bowel segment, the endometriotic nodule of the sigmoid colon was previously demonstrated by MSCT [14].

Figure 7: Endometriotic nodule infiltration the muscular layer, A: Axial MSCTe image of the abdomen, the arrow indicates

the endometriotic nodule. The lesion is enhanced, and it infiltrates the bowel wall involving the muscular layer. B: Coronal

reconstruction demonstrating the extension of the sigmoid endometriotic nodule (indicated by the arrow) C: Formaldehydefixed

resected bowel segment, the endometriotic nodule of the sigmoid colon was previously demonstrated by MSCT [14].

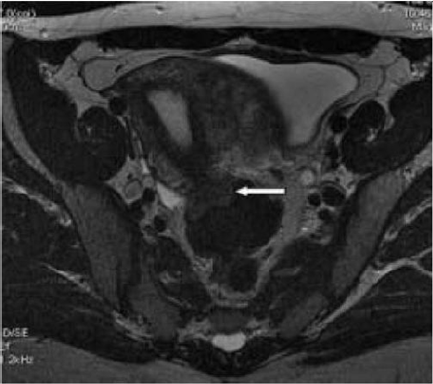

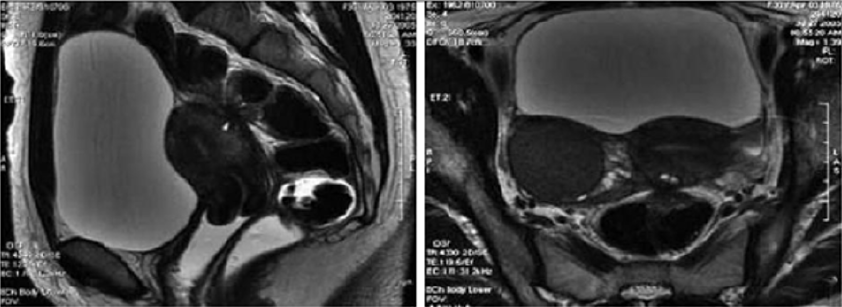

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a high sensitivity (77%-

93%) in the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis. The depth of rectal

wall infiltration by endometriosis is poorly defined by MRI. A

combination of MRI and rectal endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)

has recently been proposed. When retroperitoneal infiltration is

present, it is mandatory to know if the bowel wall is involved in

order to identify patients requiring bowel resection. Both rectal

EUS sensitivity and negative predictive value range from 92% to

100%. The specificity and positive predictive value are rather poor,

which are 66% and 64%, 83% and 94%, respectively, as reported

in two different studies [1]. Imaging examination is thus essential

for the preoperative diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis, but

some reports have described preoperative confusion between this

disease and cancer according to colonoscopy and CT with barium

enema, particularly in patients with lesions involving the mucosal

surface. In such patients, MRI is helpful for differential diagnosis.

In a typical endometrial lesion, MRI showed signal hyperintensity

on T1-weighted imaging and signal hypointensity on T2-weighted

imaging. However, smooth muscle components are reportedly

recognized frequently in endometrial lesions. In such lesions, as

seen in the present case, MRI indicates signal hypointensity on

both T1- and T2-weighted imaging, and differential diagnosis from

other diseases such as cancer and gastrointestinal stromal tumor

is thus difficult. In fact, Chapron et al reported that MRI specificity

for deeply infiltrating endometriosis was 97.9%, but sensitivity was

only 76.5% [3] (Figures 8 & 9).

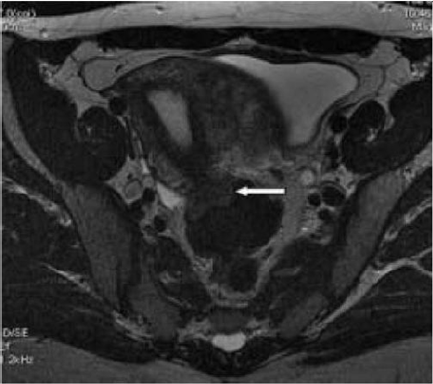

Figure 8: T2- weighted axial view: fecal matter attached to the rectal wall, simulating thickening of the rectal wall [17].

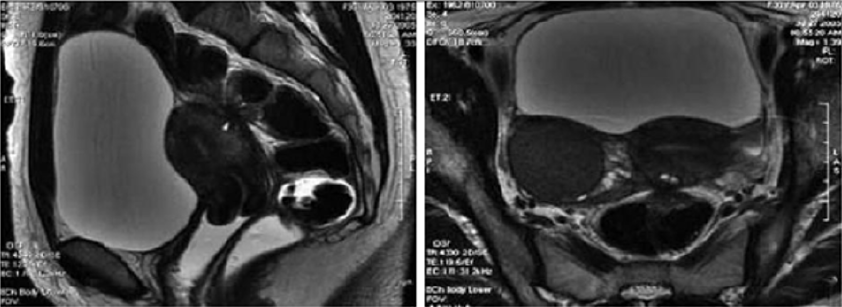

Figure 9: T2- weighted sagittal (a) and axial (b) views.

Nodule of the rectosigmoid junction adhering to the posterior surface of the uterus [17].

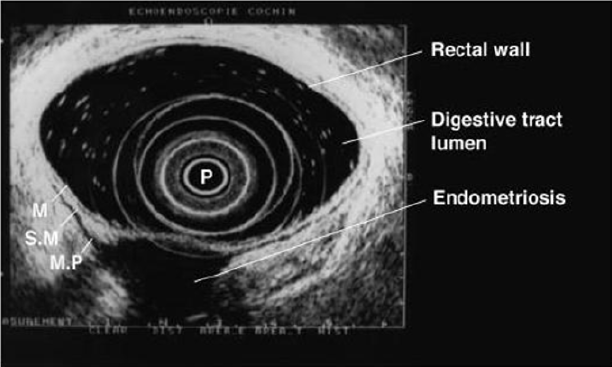

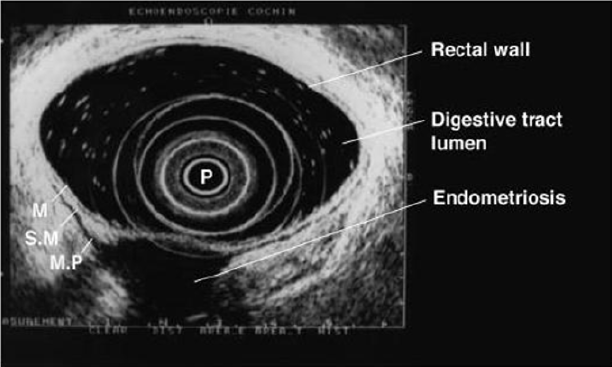

Transrectal EUS

The involvement of the colon is difficult to detect because the

implants rarely invade through the intestinal mucosa. For this

reason, the rectal ultrasound is of primary importance to assess the

rectal involvement [11]. Also, the depth of rectal wall infiltration

by endometriosis is poorly defined by MRI. A combination of

MRI and rectal endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has recently

been proposed. When retroperitoneal infiltration is present,

it is mandatory to know if the bowel wall is involved in order

to identify patients requiring bowel resection [1]. Endoscopic

ultrasonography is also a useful and noninvasive examination for

the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis. Sensitivity and specificity

are reportedly about 97% for the diagnosis of rectal involvement in

patients with known pelvic endometriosis. In addition, EUS-FNAB

provides accurate tissue and may be the only procedure for correct

preoperative diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis, but the overall

specificity, sensitivity and accuracy of EUS-FNA for neoplasms

of the gastrointestinal tract are reportedly 88%, 89% and 89%,

respectively [3]. Among these examinations, it is considered that

MRI and EUS (and/or EUS-FNAB) are the most useful examinations

for intestinal endometriosis. However, it is important to perform

valuable examinations for diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis,

including radiological, histological and etiological examinations, as

the condition basically involves a benign lesion requiring minimally

invasive treatment [3] (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Rectal endoscopic ultrasonography showing a uterosacral endometriosis nodule (2 cm x 3 cm) with bowel infiltration.

P = probe, M = mucosa, SM = submucosa, MP = muscularis propria [18].

7- Serum Markers

There is a great interest in the use of serum markers to diagnose

endometriosis, but they are not sufficiently accurate for use in

clinical practice. Cancer antigen CA-125 has been used to monitor

the progress of endometriosis [16]. CA19-9 has a lower sensitivity

than CA-125, and cytokine interleukin-6 may be more sensitive and

specific than CA-125 [1]. Mol et al reported a systematic review of

the diagnosis of endometriosis and concluded that serum CA125

level may be elevated in endometriosis, but this measurement had

no value as a diagnostic tool compared to laparoscopy [3].

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is a primary diagnostic and therapeutic tool

providing the opportunity to explore the abdominal cavity and

obtain biopsies. The magnified vision enables the surgeon to operate

with the best possible exposure. Although it was once believed that

intestinal endometriosis was best managed by hormonal regimens

or surgical castration, the advent of laparoscopic surgery has

dramatically changed this approach [11] (Table 2).

Table 2:

Treatment

Despite being a gynecologic pathology, deep infiltrating

endometriosis is not of exclusive gynecologic concern. A

multidisciplinary approach involving urologists and colorectal

surgeons therefore is recommended strongly for complete

evaluation and correct management. A minimally invasive approach

offers convenient advantages concerning the surgical management

of multifocal deep infiltrating endometriosis. Traditionally, radical

surgery [17] was considered the best measure to prevent disease

relapse. However, because of the prevalence of endometriosis

among women of reproductive age and the advances in surgical

techniques, minimally invasive conservative surgery now is

encouraged more [18]. Treatment must be individualized, taking

the clinical problem in its entirety into account, including the impact

of the disease and the effect of its treatment on quality of life. Pain

symptoms may persist despite seemingly adequate medical and/or

surgical treatment of the disease. In such circumstances, a multidisciplinary

approach involving a pain clinic and counselling should

be considered early in the treatment plan. It is also important to

involve the woman in all decisions; to be flexible in diagnostic

and therapeutic thinking; to maintain a good relationship with

the woman, and to seek advice where appropriate from more

experienced colleagues or refer the woman to a centre with the

necessary expertise to offer all available treatments in a multidisciplinary

context, including advanced laparoscopic surgery

and laparotomy [19]. The objective of the treatment in pelvic

endometriosis is to cease the endometrial stimulus in order to

ameliorate the symptoms. Thus, danozol, gonadotropin- releasing

hormones, oral contraceptives, and prostaglandin inhibitors can be

used. The conclusive treatment of endometriosis is total abdominal

hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and removal of

all endometrial foci. Because malignant transformation cannot be

excluded preoperatively and medical treatment may cause fibrosis,

the definitive treatment is surgical. Also, in the case of intestinal

obstruction and severe rectal and abdominal pain, surgery is

indicated. The main objective of surgery is the resection of the

affected bowel segment, enabling the histopathological examination

of the resection material. Limited surgery, such as excision or

cauterization of superficial lesions, following confirmation through

frozen section analysis could be performed. In conclusion, intestinal

endometriosis is a disease that may imitate various gastrointestinal

system diseases. The definite diagnosis could only be done by

histopathologic confirmation, since there are no pathognomonic

radiological or colonoscopic findings. In female patients who have

unexplained digestive complaints, endometriosis should also be

considered in the differential diagnosis [20].

The Treatment of Uncomplicated Intestinal

It depends on the patient’s age and intention to conceive. Bowel

resection is indicated if there are symptoms of obstruction or

bleeding, and if malignancy cannot be excluded. In patients of childbearing

age, resection of the involved colon followed by hormonal

treatment may be sufficient; otherwise, hysterectomy and bilateral

oophorectomy is the treatment of choice [21]. Medical suppressive

therapy may be beneficial in some patients with symptomatic

rectovaginal endometriosis, but often it is either ineffective or

only temporarily effective, whereas surgical therapy is effective in

relieving pain conditions. Other studies have shown that operative

therapy of rectovaginal endometriosis does not modify reproductive

prognosis but significantly reduces pain and improves quality

of life. The best long-term results are obtained after complete

excision of the endometriotic tissue [22]. The surgeon’s judgment

on bowel involvement with the consequence of bowel resection is

of the utmost importance [22]. Redwing has suggested a severity

scoring system for intestinal endometriosis based on the form of

surgical management required: grade I, superficial seromuscular;

grade II, partial thickness to mucosa; grade III, full thickness;

grade IV, segmental. The surgical approaches to intestinal disease

include simple excision (with cautery or laser), mucosal skinning,

full thickness disc excision with primary closure, and formal bowel

resection [23]. Full thickness disc resection of bowel endometriotic

lesion is often incomplete, at least one-third of patients with

bowel endometriosis treated by full thickness disc resection have

persistent disease. The surgeons must always weigh the risk

of potential complications of surgery against the benefit of the

complete removal of bowel endometriotic lesions. To date, no clear

guideline exists for the pre-operative assessment of patients with

suspected endometriosis; therefore, bowel resections should only

be performed after a careful pre-operative evaluation of patients’

symptoms and a radiological examination of the bowel [23]. Bowel

resection can be performed according to previously published

criteria (Remorgida et al.): single lesion >3 cm in diameter, single

lesion infiltrating >50% of the bowel wall, three or more lesions

infiltrating the muscular layer [15].

Operative Technique

The collaboration of a laparoscopically skilled gynaecologist

and colorectal surgeon has been recognised as ideal in the surgical

management of colorectal endometriosis. Patients undergo bowel

preparation 24 h prior to surgery with a Fleet® ACCU-PREP®

Bowel Cleansing System (C.B. Fleet Co., Braeside, Vic., Australia)

[24]. Prophylactic anticoagulant therapy was given the evening

before the operation, and prophylactic antibiotic therapy was

given at the beginning of the operation [25]. Surgery is performed

with the patient in the lithotomy position. Five ports are used with

placement as shown in Figure 11. Five-millimetre 0° and 5-mm

30° endoscopes are used and most dissection is undertaken using

the harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., Cincinnati, OH,

USA). Pneumoperitoneum is maintained at 12-14 mmHg with a

flow rate of 40 L/min. For an anterior segmental bowel resection,

the descending colon is mobilised up to the level of the splenic

flexure. The ureter is identified crossing the pelvic brim on the

left, and mobilisation continued inferiorly to open the para-rectal

space medial to the uterosacral ligament. The right mesocolon

is then opened and dissection extended down to the right pararectal

space medial to the uterosacral ligament. The right ureter

is identified during this dissection. The sigmoid colon is then

elevated with bowel grasping forceps, and the space posterior

to the sigmoid mesocolon is opened. During this dissection the

inferior mesenteric vessels are identified and divided using an

endoscopic linear cutter 45 mm (ATW45 Ethicon Endo-Surgery,

Inc.) once the requirement for a bowel resection is established.

Further elevation of the sigmoid colon allows the posterior

dissection to continue inferiorly to the presacral plane, allowing

mobilization of the rectum. Having mobilized the rectosigmoid

laterally and posteriorly, the rectum is then dissected free from

the posterior cervix. This is the most difficult part of the dissection

and an attempt is made to free disease from the posterior cervix

and posterior vaginal wall as completely as possible. If there is coexisting

invasive uterosacral disease, this is excised end bloc with

the affected rectal segment. The inferior dissection is complete

when the normal tissue in the rectovaginal septum is encountered.

Once the level of rectal transection is identified, the mesorectum

is divided at that point leaving the rectal tube. An endoscopic

articulating linear cutter 45 mm (ATG45 Ethicon Endo-Surgery,

Inc.) is introduced and applied transversely across unaffected

distal rectum. The stapler is fired to separate the affected rectal

segment from the distal rectal stump. Two firings may be required.

The lower right 12 mm port site is then converted to a minilaparotomy

incision, approximately 3-4 cm in length. The affected

rectal segment is then delivered through this wound, clamped and

divided above the level of disease. The anvil from an endoscopic

curved intraluminal stapler 29 mm (ECS29 Ethicon Endo-Surgery,

Inc.) is secured into the proximal colon with a purse-string suture.

The proximal segment is then returned to the abdominal cavity

and the mini laparotomy wound closed. Pneumoperitoneum is reestablished.

The ECS29 is passed transanally, and the distal rectal

stump is elevated. The circular stapling device is opened, passing

a metal spike through the distal rectal stump adjacent to the staple

line. The anvil within the proximal segment is then docked to the

spike and the circular stapling device closed. The circular stapling

device is then fired to complete the anastomosis. After removing

the transanal stapler, an integrity check is performed by distending

the rectum with Betadine after occluding the sigmoid colon at the

pelvic brim. Further check of integrity is undertaken by instilling

air into the rectum after flooding the pelvis with saline. A 17-gauge

drain is left in the operative site, after which all ports are removed

[24]. Terminal-to-terminal anastomoses were classified according

to distance from the anus as high/medium (>8 cm), low (5-8 cm)

or ultralow (<5 cm). The choice to perform primary ileostomy

or colostomy was based on intraoperative findings [26]. For a

disc excision, a lesser degree of descending colon mobilization is

required, less posterior rectosigmoid dissection may be required

and there is no requirement to divide the inferior mesenteric vessels.

The principles of pelvic dissection are otherwise as described. Once

the rectal disease has been identified and isolated, a figure of eight

suture is placed through the lesion. An ECS33 stapling device is

passed transanally with the anvil intact. The device is then opened

and angled towards the rectosigmoid lesion. The suture is grasped

with laparoscopic forceps, and the disease drawn down into the

open stapler. The stapling device is then closed, rotated slightly to

ensure that the posterior rectal wall has not become entrapped,

and then fired. An anterior arc of rectal wall containing the lesion

is therefore removed and the rectal wall stapled in a single action.

Rectosigmoid integrity checks are then undertaken as described

above [24]. The extent of the lesions as well as the severity

of the symptoms justifies the extensive nature of the surgery

undertaken. The findings of additional areas of the bowel that are

macroscopically normal but microscopically involved, as well as

involvement of the lymph nodes, suggest to us that simple local

excision of a disc may on occasions be inadequate to remove the

whole of the involved area of the bowel [12]. There are no data to

justify hormonal treatment prior to surgery to improve the success

of surgery [19]. However, according to ESHRE guidelines Postoperative

treatment for endometriosis in general might include

danazol or a GnRH agonist for 6 months after surgery as it reduces

endometriosis associated pain and delays recurrence at 12 and

24 months compared with placebo and expectant management.

However, postoperative treatment with a COC is not effective [19].

Figure 11: Placement of five port sites used in Surgery.

Postoperative Complications

The risk of complications depends on the clinical conditions,

such as the level of bowel stenosis, opening of the vaginal wall, the

extent of endometriosis infiltration, and the surgeon’s experience.

Moreover, the possibility of performing this kind of surgery

(complete eradication with colorectal surgery) in a referral center

reduces the risk of complications and improves clinical outcomes.

Indeed, women who undergo intestinal surgery are at higher risk

of complications mainly in the short-term, but close surveillance

reduces the risk of need for reintervention and allows a good

recovery within a few weeks [27]. Complications include:

a) Internal hemorrhage

b) Bowel fistula

c) Vaginal fistula

d) Retention of urine

e) Constipation

f) Abdominal wall hematoma

g) Ureteral injury and stenosis

h) Bladder perforation

i) Uterine perforation

j) Cystitis

k) Adynamic ileus

l) Mechanical bowel obstruction

m) Peritonitis

n) Peritoneal effusion

Outcome after Surgery

The indications of colorectal resection for endometriosis are

controversial, and the likely risk/benefit ratio must be discussed

with each patient. No menstrual pelvic pain, pain on bowel

movement, cramping, and cyclic rectal bleeding improved or

disappeared in all the women concerned, in keeping with previous

studies of colorectal resection for endometriosis. dysmenorrhea,

dyspareunia, pain on defecation, and no menstrual pelvic pain

improved significantly, on the basis of visual analog scores, whereas

no impact was noted on pain on bowel movement, lower back

pain, or asthenia. Recent results confirm those of Redwing and

Wright, showing that women with dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia,

pain on defecation, or no menstrual pelvic pain associated with

complete endometriotic obliteration of the sac of Douglas are the

best candidates for extensive resection [28]. Bowel resection is not

completely free of recurrence of endometriosis, but the incidence

of recurrence is significantly lower [29]. In conclusion, laparoscopic

rectosigmoid resection and end-to-end anastomosis seem safe and

effective in women with deep infiltrating colorectal endometriosis,

where the bowel lumen is largely restricted, and bowel function

is greatly impaired. Results of long-term follow up demonstrate

significant reductions in painful and dysfunctional symptoms

associated with deep bowel involvement [30]. Laparoscopic

segmental colorectal resection for endometriosis is associated with

a significant improvement in quality of life and gynecological and

digestive symptoms [25].

Read More About Lupine Publishers Journal of Surgery & Case Studies Please Click on Below Link:

https://surgery-casestudies-lupine-publishers.blogspot.com/