Lupine Publishers| Journal of Otolaryngology

Abstract

Background: The National Cochlear implant program in Tanzania was established in the year 2017. Prior to this, very few children with Profound Sensorineural Hearing Loss benefited from this surgery abroad through grants from the Ministry of Health. Since the establishment of the local program, there is an increased awareness amongst parents’, and many are seeking to benefit from this initiative. The challenge, however, remains the measurements of expectations of the parents and the actual outcomes after the surgery. This is mainly due to the perspective of the parents which comes about from their understanding of the whole process of surgery and the rehabilitation after surgery that determines expected outcomes.

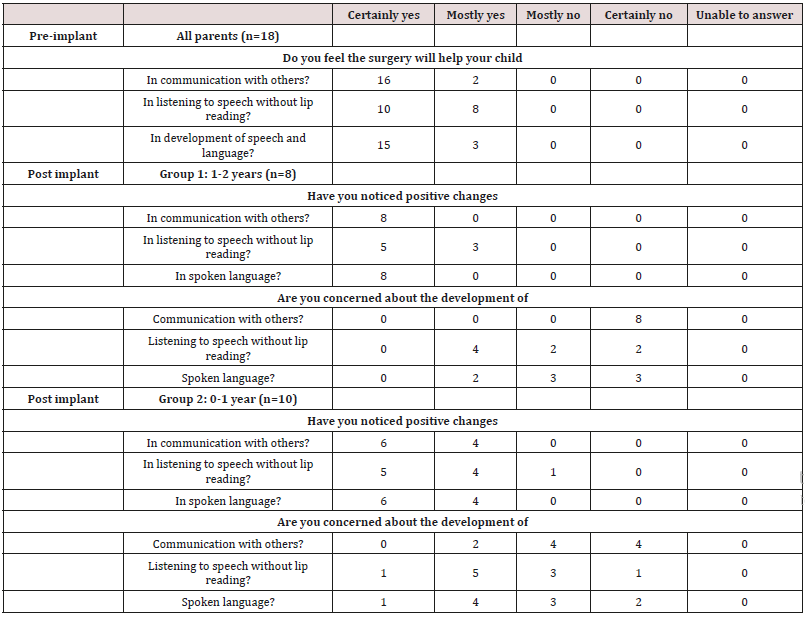

Aim: This study aims to establish a direct link between the parental perspective pre and post cochlear implant surgery. Participants: A total of 18 children between ages of 3 years and 6 years, divided in two groups, G1=children who have been implanted for 1-2 years (n=8) and G2=children who have been implanted for 0-1 years (n=10).

Method: A non-standardized closed ended questionnaire with questions on perspectives of three domains i.e. Communication, Listening Skills and Speech and Language development was administered to the parents, pre-implantation and 1year post implantation for G1 and 6 months post-implantation for G2.

Results: In all of the 18 cases, pre-implantation expectations were higher than the actual perspectives post-implantation. However, G1 parents had higher scores than G2 i.e. The preimplantation expectations were somehow met after 1 year of implantation.

Conclusion: The study demonstrates the ability of Cochlear Implantation to meet the parental expectations in the 3 outcome domains i.e. communication, listening skills and the development of speech and language. However, this is subject to the time frame post implantation i.e. the longer the time, the better the pre-implant perspectives are met.

Introduction

Cochlear implants, as prosthetic devices designed to replace the function of the inner ear, have become a widely used intervention method for people with severe to profound sensorineural hearing losses who gain little or no benefit from conventional hearing aids. Since their approval by the United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in 1990 for children as young as the age of two [1], pediatric cochlear implantation has become an increasingly routine procedure in numerous countries worldwide as a management option for permanent childhood hearing loss. The foundation of cochlear implant programs for these patients began in developed countries and over time the devices, surgical methods, and rehabilitation programs improved, which thus led to their initiation in developing countries. Prior to the commencement of locally performed cochlear implant surgeries in Tanzania, candidates for implantation had to travel to other countries for the procedure. This was a costly and intensive process for privately and government funded patients alike, a factor that fueled the need for a local program. In 2017, six children were implanted for the first time at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and to date a total of thirty patients have been implanted altogether. Over the time, since the first surgeries, local professionals and rehabilitation centers have become more proficient in evaluating and caring for these patients, and an increased awareness of hearing impairments as a whole has been observed. Perceptions regarding cochlear implants of health professionals, the general public, and in particular parents of implantees and potential candidates have also been seen to change, becoming more informed and understanding. Candidacy for cochlear implants is assessed on a case-by-case basis, with referrals for assessment primarily made according to candidacy criteria set out by the Cochlear Implant Group Tanzania [2].

Currently, the indications for cochlear implantation from an audiological perspective are as follows; bilateral severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss (typically >90dBHL at 2kHz and onwards), limited benefit from hearing aids, and the absence of contraindications for implantation. The candidates undergo thorough examinations by audiologists, speech-language pathologists, radiologists, otorhinolaryngologists, pediatricians, social services, psychologists, and other professionals where necessary. This process is not unlike guidelines in other countries with cochlear implant programs, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom make similar recommendations, although in 2018 with suggestions from the British Cochlear Implant Group (BCIG) updated the eligibility criteria to define severe to profound deafness as only hearing sounds greater or equal to 80dBHL at two or more frequencies between 500Hz and 4kHz [3]. These recommendations and procedures differ slightly between countries and programs and may also change depending on whether the candidate is privately or publicly funded. Outcomes for pediatric cochlear implantation worldwide have encouraged their use as an intervention method for hearing impairments, reinforced by their widespread success and relatively low rate of complication [4]. A prospective longitudinal study of spoken language development in children implanted before the age of five, conducted over a period of three years, revealed significant improvements in spoken language performance (comprehension and expression) particularly over the first three years of device use. Greater improvements were seen in younger children and children with more residual hearing prior to implantation, although in all children outcomes surpassed the improvements predicted by their pre-implant assessment baseline scores [5]. A retrospective study evaluating the outcomes of cochlear implantation in relation to age of implantation conducted by Govaerts et al. [6] studied children with congenital deafness who were implanted before the age of six with a multichannel cochlear implant, evaluating them using Categories of Auditory Performance (CAP) scores and correlating outcomes with age of implantation.

All children demonstrated an increase in scores postimplantation, appearing to benefit from the device. The study identified that implantation between the ages of two and four always resulted in age-appropriate CAP scores after three years of implant usage, while implantation before the age of two years always resulted in immediate normalization of CAP scores. Implantation after the age of four, however, hardly resulted in normal CAP scores, signifying the importance of early intervention in preventing losses of auditory performance following the procedure, and only 20% to 30% of these children were eventually fully integrated into mainstream primary schools [6]. While this study reinforces the significance of age at implantation as a predictor of auditory and language outcomes, it also demonstrates the efficacy of cochlear implants as intervention for pre-lingually deafened children; even in patients implanted later than recommended, significant benefits were observed and a percentage of these patients developed the ability to integrate into mainstream education.

An integral part of the process towards pediatric implantation is continued counselling of parents of patients regarding their child’s impairment, amplification, the device, the surgery, rehabilitation, and of their expectations and outcomes. Parental expectations prior to implantation are considered a key factor in the process of candidacy assessment, so much so that they have been used previously as a criterion in the evaluation of the child’s eligibility for an implant [7]. Without the appropriate counselling and guidance, parents can be led to believe that the implant will work on its own, and that the child will be able to hear and speak shortly after switch-on [8]. Kampfe et al. [7] identified that these expectations can be influenced by the fact that the device is very expensive and high-tech, leading to unreasonable expectations. They also suggest that these expectations can also be partly due to the influence of the media, which presents the implant as an immediate change to hearing – often showcasing only significant reactions of patients in response to sounds [7]. Twenty-six years later, this statement still holds truth, as videos of ‘sensational’ reactions to sounds by implantees are spread on social media and on the news, particularly in countries where programs are in their infancy. These can lead to unrealistic expectations, subsequent stress, and disappointment when their expectations are not met. Families’ stress in relation to cochlear implants has been looked at in numerous studies and is due to a number of sources [9]. One such source is the surgical procedure itself. Although the procedure is quite safe with a low chance of complications [4], it is still a surgical procedure that has its risks, and this results in some anxiety or worry experienced by the parents [9]. It is vital that the procedure is explained appropriately to parents, and sources of clear information about it and the risks it may pose are made easily available. Another source of stress, as previously identified, is the parent’s perceptions when their expectations are not immediately met [10]. Over time this lessens as a stressor particularly as children begin to show improvements. In order to better understand parental expectations, it is important for clinicians to be aware of the reasoning behind their choice in going forward with implantation. A study by Sach & Whynes [11] interviewed 216 parents of children implanted at the Nottingham Pediatric Cochlear Implant Programmes using a mix of structured and open-ended interview formats. When asked about the decision to implant their child, 38% of parents stated that the benefit they expected was ‘improved hearing’, 23% anticipated psychosocial and behavioural benefits, 19% mentioned greater opportunities later in life while 16% cited improvements in speech [12].

In most cases outcomes were reported to be in line with their expectations, and 93% of interviews mentioned ‘improved hearing’ as an outcome of implantation. When interviewed about their expectations, 5% of parents admitted to having high and unrealistic expectations, while 16% mentioned that initial expectations had been low. With its large sample size and extensive data collection, this study has provided an insight into parental perspectives of cochlear implantations and the effect various factors can have on stress, expectations, and outcomes [12]. A study by Hyde et al.

investigating parental expectations and [13] experiences related to their children’s outcomes with implants, surveyed 247 parents in eastern Australia, and compared reports of pre-implant expectations with post-implant outcomes. Findings from this study indicated that while parents had relatively high expectations, these had mostly been met by their children’s outcomes post-implantation. 10% of parents, however, reported that expectations had not been met. Furthermore, the study established that professionals generally did a good job in providing parents with realistic expectations prior to implantation and during rehabilitation [13].

A child’s home and family environment can lead to variations in outcomes seen in implanted children [10,14,15]. Perspectives of parents and guardians towards the device and their children can influence development of the implanted child, as they can affect factors such as the level of support given at home, roles undertaken by family members in therapy, their interactions with the child, and organization and control in homes [14]. Amongst outcome predictors such as duration of deafness and learning style, family structure and support has been identified as a significant predictor of outcome following cochlear implantation as demonstrated by use of the Nottingham children’s implant profile (NChIP) to assess children, family, and support services prior to implantation [16]. Various studies into predictors of spoken language development and good outcomes with cochlear implantation have supported these findings. Better outcomes have been associated with lower ages at implantation [17], early identification of hearing impairment, number of active electrode channels effectively ‘mapped’, and bilateral implantation when compared with unilateral or bimodal stimulation [17]. Boons et al. [17] divide predictors of language development in pediatric cochlear implant recipients into three categories:

a) Auditory factors such as age of implantation or identification,

b) Child-related factors such as the presence of other disabilities and etiology of hearing loss, and

c) Environmental factors such as parental involvement and socioeconomic status.

A retrospective study into these factors involving 288 prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants was conducted through the use of numerous validated outcome measures and standardized questionnaires. The study identified that amongst the factors that can influence outcomes of cochlear implantation, environmental factors related to parental characteristics played an important role. One such factor was the communication mode between parents and their child, as participants were asked whether communication was oral, total (using signs along with spoken language), or bilingual. Another factor looked at whether the parents’ involvement in the rehabilitation process was ‘sufficient’, as it would be in a well-functioning family, or ‘insufficient’ if parents were seen to be unmotivated or unable to fulfill commitments in relation to the child (Table 1).

Boons et al. [17]acknowledge the oversimplification of these classifications and have identified that while it is not a validated measure of parental involvement it can suggest an undesirable attitude of parents towards the child’s impairment and rehabilitation. 96% of parents in this study were seen to be sufficiently involved in their child’s rehabilitation, but in 4% of cases issues were mentioned highlighting insufficient involvement in the process. This factor did not show a significant variation in outcomes in the first two years following implantation, but after a certain amount of time the study identified that the advantages and possible positive effects of a supportive environment become measurable. Multilingualism in communicating with the child also consistently correlated with lower language scores over time and was accompanied by low parental involvement in rehabilitation. These findings suggest that the effects of environmental factors increased as time went on and were more measurable after two years post-implantation [15,17] also reported more significant individual variations in outcomes in children over time and found that levels of parental involvement in the rehabilitation process was associated with children’s linguistic ability four years after implantation [15]. In comparison, higher language achievement in implanted children was associated with parents reporting lengthier and detailed processes in deciding about the implant pre-implantation and who showed a higher level of involvement and commitment with the child’s rehabilitation post-implantation [15]. This correlation was also identified by Niparko et al. [5], who found higher parent-child interaction scores being significantly associated with greater rates of increase in comprehension and expression of spoken language [5]. These findings are supportive of the conclusion that variability in parental involvement, quality and quantity of parent-child interactions, and commitment to rehabilitation are significant factors in outcomes of children with cochlear implant and can lead to significant measurable differences in spoken language development after longer periods of time.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.